As part of their contributing work to the Healing with Play initiatives, our project team museums participated in a series of case studies, authored by Knology, dedicated to exploring the different ways children’s museums are supporting bereaved children and families in their communities.

Looking to offer bereavement-related programs, events, or services to children and families in your community? For helpful guidance on how to get started, see issues 8.1 and 8.2 of the ACM Trends Report series. And if your museum is already providing bereavement care to children and families, we’d love to hear from you to learn about your experiences! You can get in touch with us at Blythe.Romano@ChildrensMuseums.org.

On October 4, 2024, the Grand Rapids Children’s Museum launched the i understand Kimberly Mutch Bergner Mental Wellness Exhibit, Weathering Emotions. Created in memory of Kimberly Mutch Bergner, a mother of four who lost her life to depression, the exhibit was inspired by two books — one, called Ocean Meets Sky, in which a young boy embarks on a dreamlike voyage to find his deceased grandfather, and a second written by Vonnie Woodrick called Marshmallow Clouds, which tells the story of the author’s son visiting his father in the clouds. As Chief Operating and Financial Officer Erin Crison explains, much like the children in those stories, the exhibit’s goal is to help children stay connected to lost loved ones – to get them to realize that even after someone dies, “You can still talk to them, because their memory is still here.”

Visitors to the Mindful Movement station practice mindful breathing and yoga as their shadow interacts with raindrops and clouds in a peaceful dance. As Crison explains, the station reflects the museum’s interest in having “technology that reacts to kids.”

The exhibit (click here for a behind-the-scenes video) consists of five stations, all of which are geared toward helping children build emotional intelligence and resilience. Part of developing these skills, Crison explains, is figuring out how to “process and slow down.” To effectively work through uncomfortable feelings, she adds, children need experiences that help them “stop, take a breath, and observe what’s going on” – both around them and inside them.

Inside the exhibit’s Sound Cloud, visitors can hear the rumble of thunder, watch lightning flash, and feel the weather around them shift. The point of associating weather conditions with emotional states, Crison says, is to teach visitors that just like storms, feelings related to loss and grief are things “we can navigate our way through.”

At the exhibit’s emotional storyblocks station, children select blocks listing different life events (for example, “I watched a funny movie,” “I spent time with loved ones,” “I lost a shoe,” “Somebody died”) and then spin a dial to associate that event with different weather conditions (for example, “sunny day,” “cumulonimbus cloud,” “storms,” etc.). After their turn at the station, visitors print out a coloring sheet to take home that includes a number of different bereavement resources.

At the Mindful Movement station, visitors watch their shadows dance against a backdrop of raindrops and clouds while a calming voice (provided by Ginger Zee, Chief Meteorologist and Chief Climate Correspondent at ABC News, and a contributor to the exhibit content)

guides them through mindful breathing and yoga. At the Affirmations Mirror, visitors see their own reflections, and are encouraged to build resilience and strength by making and reflecting on positive affirmations about themselves. Upon entering the Sound Cloud, visitors gain the ability to control the weather, creating lightning, thunder, and other natural phenomena that mimic different emotional states.

The two other exhibit stations explicitly deal with bereavement. At the Grief Station, visitors encounter a transparent acrylic glass cloud connected to a wind tunnel. After writing a message to a loved one on a paper raindrop or hot air balloon cutout, visitors then release that message into the wind tunnel, where it floats into the clouds.

At the Emotional Storytelling station, visitors use story blocks and a weather dial to articulate their feelings in connection with different life events. When selecting the block that reads “somebody died,” visitors can spin the dial to identify the weather they associate with bereavement (for example, “stormy weather”). After this, a coloring sheet is printed out that contains a list of bereavement-related resources.

The idea behind these activities is, first, to help children identify and articulate bereavement-related feelings, and second, to give them some tools for navigating those feelings. Though grief is “present everywhere,” Crison says, “as a society, we do a terrible job talking about it.” “Children have to discuss the hard things, and need the tools for having those conversations,” she adds. In likening grief and other uncomfortable feelings to storms, Weathering Emotions seeks to teach children that these feelings are temporary — and that “with the right understanding of what’s going on, we can navigate through them.” As Crison explains, “sometimes we need to step back, listen, and let children process their emotions.”

The exhibit was eighteen months in the making. Partnerships were critical to its creation. In addition to working with i understand (who helped develop and provided the financial support for the exhibit), the museum collaborated with design partners CARNEVALE and Meta4Mat, and with local school districts. Especially valuable was the design input the museum received from sixth grade students (who, as Crison notes, are at the age where it’s hardest to talk about one’s emotions). Those youth who participated in focus groups “really embraced the conversations,” and offered valuable feedback, Crison says. After designing the exhibit, the museum also beta tested it with children. Their reactions convinced the museum they were really onto something.

The community response to Weathering Emotions has been positive. Children and families often talk about the exhibit inside the museum, and the pieces of paper staff have collected from the Grief Station indicate that visitors are benefiting from the experience. Along the way, some staff who were initially unsure about the exhibit have come to recognize its value. “It was a hard jump for some of our team members,” Crison acknowledges. Thinking that children “have to be actively doing something at all times,” some staff asked, “What are the kids going to do in there?” But after seeing that youth were benefiting from the chance to identify, articulate, and express their feelings, everyone on the team came around.

One of the exhibit’s stations, Crison explains, came directly from a boy who described an emotional state as “feeling like a tornado.” At this station, visitors can feel a tornado swirl around them as they learn about forces of nature that mimic emotional whirlwinds.

The experience of designing and hosting Weathering Emotions has given museum staff a deeper appreciation of the support they can provide to bereaved children and families. One thing the exhibit helped staff realize, Crison says, is that to effectively meet bereaved visitors’ needs, children’s museum professionals do not need to become grief counselors or experts on the subject of death and dying. “There’s power in not being an expert and having a kid come talk to you and say ‘I feel sad’ or ‘I don’t like the way I feel,’” Crison says, adding that often, what helps bereaved children the most is “just that moment of listening and compassion.” Instead of feeling that they need to have answers to every single bereavement-related question children have, she says, “it’s okay for staff to just listen or just to embrace that sadness.”

Visitors at the exhibit’s Grief Station write messages on raindrop-shaped slips of paper that are floated out into the clouds via a glass wind tunnel. The idea for the station, Crison explains, is similar to that of the “symbolic balloon release” – a well-known means of paying tribute to lost loved ones that is also effective in helping the bereaved let go of anger, pain, and sadness.

Crison has also come away from her museum’s experience with a broader understanding of how the field as a whole can integrate bereavement care into their work with children. It’s beneficial to let museums “become a space where all emotions are felt and not just good emotions,” Crison says. ”If kids don’t have a bridge to connect those extreme emotions,” she continues, “they’re going to get stuck in spaces that are dark and stormy, and will feel overwhelmed.” But by “anchoring hard topics in playful settings,”children’s museums can help bereaved visitors discover that “happiness isn’t so far away from the sadness.” Agreeing with this, museum CEO Maggie Lancaster likens Weathering Emotions to the field’s embrace of “risky play.” “We like to take these physical risks so that when you go on in life, you’re prepared,” she says. “The same applies to emotional risks too. We shouldn’t treat grief any differently than we treat risky play.”

Tennessee has the fifth highest childhood bereavement rate in the US; according to data from Judi’s House, at present, one in every eight children in the state will experience the death of a parent or sibling by age 18. To help meet the needs of bereaved families, on November 23, 2024, the Children’s Museum of Memphis (CMOM) hosted a “Day of Resilience.” Sponsored by the New York Life Foundation, the four-hour event included activities for the general public and a storytime program for parents and children with recent experiences of loss.

A flyer announcing the museum’s Day of Resilience, which was held on November 23, 2024.

Dr. Stewart Burgess is the museum’s executive director. A psychologist with over 25 years of experience in the field of child development, Burgess is passionate about fostering positive learning experiences for children. During his tenure at CMOM, Burgess has overseen the development of an ecological model of community support – something that helps the museum understand the “whole system around families and children” in Memphis, with an aim toward “plugging gaps” tied to disruptive events (illness, poverty, having a parent overseas, etc.) in children’s lives.

Bereavement is one of those events. When children lose a loved one, Burgess notes, “a lot of the happy routines in a family disappear.” Places that used to be a source of joy for the entire family “suddenly become too painful to possibly bear.” At the same time, children may lose sources of family support. Those experiencing grief over the loss of a loved one tend to “bottle up their emotions,” Burgess explains. Because they’re often “inside their heads” and “don’t want to make others sad,” adults may not want to share their grief with children. For their part, children who see the effects bereavement is having on their parents often “don’t bring it up because they don’t want to make the adults sadder.” Either way, “we end up with silence.”

CMOM’s “Day of Resilience” was intended to plug some of the gaps in our current bereavement care infrastructure. Prior to hosting this event, the museum had established a partnership with the Kemmons Wilson Family Foundation — whose Family Center for Good Grief offers services and support to bereaved children and families throughout the region. After touring the Center’s facilities and learning about the therapy they offer children, Burgess invited Foundation representatives to the museum for discussions about how they might work together (for example, giving children discounted or after-hours access to the museum). These conversations convinced Burgess that the museum “needed to pick up the baton in a bigger way.”

Shortly after that, the New York Life Foundation broached the idea of having a bereavement day at the museum. After several months of planning, the three partners arrived at an agenda for the day. While bereavement was a component of the day’s activities, the broader focus was on “how to express your emotions when you miss someone.” Negative feelings associated with missing another person, Burgess explains, often cause people to become “stuck,” which can lead to helplessness and dysfunction. But when given ways to get those feelings “out of our stomachs, and out of our heads,” the results can be quite cathartic: it “gives you a little control,” and “helps you become unstuck.” Because of this, there’s value in having opportunities to name, describe, express, and communicate difficult feelings to others — either with words, or through arts and crafts.

That was the basic idea for the museum’s Day of Resilience: to give families ideas on “what you do with negative emotions.” Within the pavilion wing of the museum, CMOM staff created two large stations for general public use. The first was a community mural. Housed within the museum’s art lab, the mural consisted of a large roll of paper placed on a giant table. Using various art supplies, visitors were encouraged to draw, color, and write in ways that depicted feelings associated with missing someone. Some drew hearts, or objects that reminded them of the person they missed. Many drew pictures of themselves and those they missed, adding text that explained what they loved about them. Others opted for more abstract representations of their feelings, using light or dark colors to express themselves.

At the second station, visitors filled empty glass jars with private messages to those they were missing. Using small slips of paper, participants could write about anything they wanted to share with that person — for example, “I thought of you today because I had your favorite ice cream,” or “I’m excited about you coming back to school when you’re feeling better.” Like the mural, parents participated in the jar activity “right alongside their children” — something that gave them an opportunity to model healthy ways of expressing emotion. Yet whereas the mural was a “one-off” activity, families brought the jars home, and were encouraged to continue filling them with more and more notes. Doing this would help them “keep those relationships alive” and promote the sharing of thoughts, feelings, and memories with others — both of which are critical to dealing with loss and grief.

During its Day of Resilience, CMOM created a community mural that children and families could use to draw pictures of people they missed. The activity gave participants a chance to visually represent feelings associated with loss and grief.

In addition to the mural and jar activities, CMOM’s Day of Resilience included a bereavement storytime program for families receiving professional support from the New York Life Foundation. Held in a private room, this program gave bereaved families (who were given free access to the museum through the Foundation) a chance to learn about books and other media that could be used to prompt productive, healing discussions about those they had lost. New York Life also set up a series of resource tables full of pamphlets, brochures, guidebooks, and information about bereavement materials available online — all of which served to increase public awareness of available resources at the local and national levels.

CMOM’s Day of Resilience was “really well attended, and we got a lot of feedback,” Burgess shares. All of it was positive. Families said they were “really pleased” with the museum’s efforts, thanking CMOM for activities that were both “educationally enriching” and that gave them practical, concrete things to do “when they get into that difficult spot” emotionally. The day was “really gratifying” for the museum as well, particularly as it underscored the importance of being proactive when it comes to equipping people with strategies for working through uncomfortable feelings. As Burgess notes, being aware of ways to process grief and loss before tragedy strikes is critical, because “when you’re in crisis, you don’t know what you need until it’s too late.” Given that, it’s best to take the opportunity to “make people more competent and help them build their armor and skill sets beforehand.”

Through its Day of Resilience, CMOM was able to do that. “We’re not a clinical practice and we can’t do follow up,” Burgess says, “but we can still try to give people the tools, skill sets, and modeling they need to work through negative emotions.” Burgess came away from the event convinced that it was worth it to “take the risk and venture into this area.” To support other museums looking to become sources of bereavement care, he recommends the following as first steps to entering this space:

Read up on the research — Acquiring a basic, general level of familiarity with the bereavement literature will ensure that the programs, services, and resources children’s museums provide are “things that every counselor would agree on.”

Survey the local landscape — “Don’t ignore the fact that you probably have existing resources in your area,” Burgess advises. Doing this will equip staff with information about local sources of bereavement care that can be shared with visitors.

Partner up with experts — “Don’t try to be an expert,” Burgess says — especially when “there’s an expert down the street who would happily provide their services.” By partnering with bereavement professionals, children’s museums save themselves time (by not having to “reinvent the wheel”) and “become really comfortable about the validity of what they’re doing.”

Get training — Bereavement organizations are generally “very happy to come in and train staff” on the basics of bereavement care, Burgess explains. Participating in training sessions can help staff learn about how to have productive interactions with bereaved children and families — in addition to understanding situations in which professional counseling support is needed.

Burgess also notes that bereavement-related programs, events, and services should be planned carefully. “You don’t know what everybody’s background is, and how sensitive they are,” Burgess cautions. Often, a “light touch” might be the best approach. But “being supercautious could also mean missing an important opportunity” to help those in need — and to equip families with important resources and practices in the face of future tragedies. Working with partners and speaking with community members beforehand is the best way to create an effective plan.

More generally, it’s important to encourage bereaved families to keep visiting “playful and fun” places. In the aftermath of a loss, Burgess says, these places are “probably needed more than ever,” because they provide children with “a release of sadness and pressure.” “Try not to make it so they stop playing,” Burgess advises; “let them smile and let them run around, because that’s one of the ways they’re wired to deal with stress.”

At the Providence Children’s Museum (PCM), staff are committed to offering children and families tools for navigating loss in all its varied forms. “We regularly support families who are experiencing grief,” says Heidi Brinig, a recently retired program director (and current consultant) at the museum. In recognition of this fact, PCM offers a variety of social-emotional learning programs and resources designed to help visitors talk about loss — whether it be the death of a loved one, a friend moving to a different school, separation from family members, or the loss of a favorite toy. A key goal of their efforts, explains Director of Education Andrew Leveillee, is to “build the capacity for resilience before families need it.”

At the Providence Children’s Museum (PCM), staff are committed to offering children and families tools for navigating loss in all its varied forms. “We regularly support families who are experiencing grief,” says Heidi Brinig, a recently retired program director (and current consultant) at the museum. In recognition of this fact, PCM offers a variety of social-emotional learning programs and resources designed to help visitors talk about loss — whether it be the death of a loved one, a friend moving to a different school, separation from family members, or the loss of a favorite toy. A key goal of their efforts, explains Director of Education Andrew Leveillee, is to “build the capacity for resilience before families need it.”

Through the project, the museum has provided regular public programming designed to promote connection, emotional literacy, and resilience skills. Through their “Mindful Moments” program, visitors can participate in playful activities, including “Joyful Movement,” which focuses on the mental health benefits of the mind-body connection, and a craft where children create “Monster Breathing Buddies” to help them calm their bodies in times of excitement or stress. These activities are designed to give children and families skills that bolster their resiliency “tool kit,” which can help them respond to difficult situations that may arise in the future, including loss.

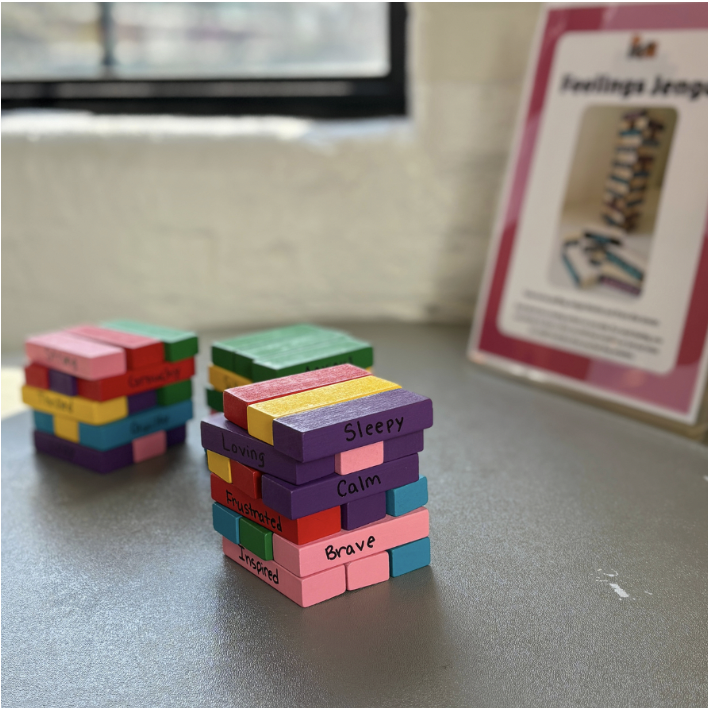

As part of its Mental Health Initiative, PCM visitors can participate in a variety of activities designed to promote emotional literacy – including “Feelings Jenga,” which helps children develop the vocabulary for thinking about and communicating their emotions.

PCM began this work through its “Families Together” program, an innovative visitation program for court-separated families that offers participants a welcoming, stimulating, safe environment for family interaction. Brinig, a mental health therapist in her previous work, directed the program for 33 years. Families Together was designed for families involved with Rhode Island’s foster care system in 1992, in collaboration with Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF). Through the program, families make a series of visits to the museum over a period of several months with their assigned family clinician, who provides coaching and support as the families work toward reunification or permanence. Playing at the museum is a cornerstone of the program, as it encourages conversation and problem-solving as family members develop new relationships and ways of communicating with each other. During visits (which take place when the museum is open to the public or at an off-site location), the Families Together clinicians and experience coordinators at the museum encourage parents and children to play together and use their shared experiences and memories to strengthen their relationships.

None of the above programs would have been possible without the support of PCM’s partners. Collaborating with others who are “well-versed in this level of work for children and families is very important,” Brinig says. When she developed Families Together, Brinig’s first goal was to better understand those social service recipients who were already using PCM facilities informally. In the process of inquiring into their needs, she established formal partnerships with social service providers. Among other things, collaborating with these providers has opened new opportunities — for example, special programming days for partners, in which “the museum becomes theirs for the families and children they serve.”

Partnerships with Adoption Rhode Island and FRIENDS WAY have been key to the success of PCM’s Mental Health Initiative

PCM’s current partnerships also make it possible for staff to participate in regular, ongoing trauma-informed training. As a result of this training, staff have become familiar with grief-specific language, tools for dealing with loss, and important needs assessment techniques. This is incredibly important, says Leveillee, because museum staff often “may not know the full scope of challenges children are carrying with them in their daily lives.” Program participants sometimes experience intense emotions. As an example, Brinig shares how those in the Families Together program often become visibly emotional during their time together, with crying, yelling, and expressions of anger or frustration being common. At the end of a visit, children frequently “don’t want to leave.”

By taking what they have learned from partners and “infusing it into the bones and structure of our practice,” Leveillee explains, PCM staff are able to effectively meet visitors’ needs “in their moment of crisis.” One way the museum does this is by maintaining a dedicated, private space within the museum where visitors who “need a moment to collect themselves” can go to. Whenever someone is feeling upset or needs to have “an emotional moment outside of the public eye,” Brinig says, they can go there for however long they need — stepping back, taking a breath, and ensuring that their emotions “are not on public display.” Beyond this, receiving training in trauma-informed practices helps the museum provide a “referral process” for partners. “If we know we have a family that’s struggling,” Brinig says, “we can contact the social service provider and ask them to spend more time talking with them in a therapeutic setting.”

In the process of creating glitter jars like that pictured above, PCM visitors learn valuable techniques for calming down during stressful times.

Lessons learned from training have also been incorporated into PCM’s programs. “One of the key lessons we took from training,” Leveillee explains, “was how to determine what kinds of program content are developmentally appropriate for children.” Generally speaking, PCM is committed to not policing play, and wants children to be able to freely explore and process their feelings in an environment that promotes “open-ended experiences” and “doesn’t put boundaries” around what they can and cannot do. Their training taught PCM that children best process loss through pretend play, and that more often than not, “you’ve just got to let it play out.” But even while tabooing certain topics “can be problematic,” Leveillee says, some situations are off-limits. “We avoid scenarios that involve violence or role-playing death,” Leveillee clarifies. The goal is to give children a vocabulary for “articulating some of the larger feelings they’re having.”

In addition to responding to children and families’ in-the-moment needs, PCM also strives to ensure that its work is as proactive as possible. Taking a proactive approach, Leveillee explains, gives people a way to “dip their toes into the water,” he continues, noting that when families are “not living it right now,” the topic of loss is “not as heavy” as it might be otherwise. Toward that end, in addition to its programs, the museum also maintains a mental health resource library designed to equip families with tools for navigating conversations about loss and other related topics. Many of the resources in this library have been created by PCM itself — including a podcast series that offers “snapshots of what the field of kids’ mental health looks like right now” and other publications that give families a “digestible way to get some of that information.” By aiming their efforts at those who “may be affected at some point,” the museum is helping them develop strategies for responding to loss before it happens — even if their initial response is something along the lines of “I don’t need those skills or capabilities right now.”

The museum has also recognized the importance of approaching grief in a broader and more accessible way, rather than focusing exclusively on bereavement. At times, PCM’s mental health programs may feel intense or overwhelming for some visitors, Leveillee explains. Some visitors may not be ready to immediately engage in conversations about the loss of a loved one. To create a more welcoming environment, the museum balances sensitive topics such as grief and loss with discussions of everyday emotions — like happiness and sadness — making the experience more relatable and approachable for all families. This approach of combining more general topics with “more of the specific language around grief” has been a successful one for the museum, Leveillee notes. “It doesn’t always have to be the most serious loss,” Brinig says. Outside of the death of a loved one, “there’s still a lot of room to talk about loss and change.”

PCM also takes a child-centered approach. When creating programs and resources that deal with loss, Leveillee says, it’s important to remember that adult understandings of and responses to loss are different than those of children. To avoid the “potential misstep” of creating content that reflects adult perspectives on loss, in all of its work, the museum foregrounds children’s lived experiences — including their anxieties, their fears, and their circumstances. Doing this helps ensure that their programs and resources are “totally age appropriate and developmentally appropriate as well.”

The response to PCM’s efforts has been largely positive. Internally, staff strongly support the museum’s efforts to equip children with tools for dealing with loss. “We could never do this work,” Brinig says, “without the support of staff, from experience coordinators up to the director.” The broader community has also gotten behind PCM’s mental health and emotional resilience programs. In part, this is because visitors have directly benefited from them. As an example of this, Brinig mentions that when others are in the museum during the Families Together program, they sometimes observe what’s happening, and come to realize that their own struggles are not unique — which can help ease feelings of isolation and reinforce that they are not alone in their parenting journeys. They also come away with ideas for handling difficult situations that can be “incorporated into their own thinking.”

PCM’s experiences have taught staff the importance of approaching the subject of loss with preparation, care, and sensitivity. Part of this comes through public-facing messages. “We always have to work with the public to ensure there’s some level of compassion and understanding,” Brinig says. Leveillee also recommends that museums strive to keep things professional — for example, by showing visitors how their program content is research-based, or by engaging in “diplomatic conversations” when necessary. Strategies such as these can help museums build support for their efforts.

So can keeping things child-centered. “One of the things that we’ve found to be successful,” Leveillee says, is “keeping things at a very foundational, kid-friendly level.” By ensuring that the programs and resources they design do not assume much in the way of prior knowledge, museums can avoid confusion and misunderstandings around what they’re trying to do. “Children often provide an important entry point for engaging adults in meaningful conversations,” Leveillee says. Beyond that, creating content that is “easy to digest” maximizes pathways for conversation, connection, and shared memory-building between children and their caregivers.

A third key lesson is the importance of partnerships. As PCM’s work indicates, offering programs and resources around this subject can result in uncomfortable experiences — both for staff and visitors. But because “lots of museums have social service partners,” Brinig says that the industry is well-positioned for success in this area. By embedding these partners into their efforts, museums can get a better sense of “who those folks are and what they need.” Through training and collaboration, they can gain the confidence and competence to “experiment and try different things” — which “really matters,” Brinig says.

A collection of “Monster Breathing Buddies,” made by children who have participated in PCM’s Mental Health Initiative activities.

A final piece of advice is to take a broad approach to the subject of loss. “We all deal with loss every day,” Brinig notes. By not focusing exclusively on any particular type of loss, Leveillee says, museums can ensure that “more people benefit” from their efforts. Keeping the scope open also helps families see that the generalized skills they acquire “can serve multiple purposes.” And that, Leveillee explains, reflects PCM’s broader mission. Rather than knowing “the facts of X, Y, and Z,” Leveillee says, it’s important that children “learn the skill to do X, Y, and Z.” Whether it’s programming around social-emotional learning, grief, or bereavement, the museum’s key questions are the same: “what are the skill sets that we would like children and families to utilize, and how do we give them opportunities to use those skills?” This approach has been key to the success of the museum’s mental health and emotional resilience programs.

Every November, the Children’s Museum of Fond Du Lac (located in Fond Du Lac, Wisconsin) hosts a special event in observance of Children’s Grief Awareness Month. Called “Super Saturday,” the event consists of a variety of fun activities aimed at helping children discover strengths and skills for coping with loss. ”We’re trying to show children and families that they can overcome hard things—that they have the powers to do this,” says Andrea Welsch, the museum’s Chief Executive Officer.

“So much of what we’re doing,” Welsch says, “is teaching families things they can do at a later time, when they’re going through grief.”

Super Saturday grew out of a long-running partnership between the museum and SSM Health St. Agnes Hospital, who began working with each other in 2008 to promote children’s health. After collaborating on a number of programs and exhibits focused on physical activity, healthy eating, and brain development, in 2015, leaders from Agnesian Healthcare (now SSM Health) asked if the museum would be interested in working with their bereavement team to put on a special event during Children’s Grief Awareness Month. The idea was to give children in the bereavement team’s care access to fun, joyful activities—and to expand community knowledge in ways that help all families become better prepared for dealing with loss.

The museum completely embraced the idea. “We were very open to expanding our collaboration in this way.” Welsch recalls, noting that “Since their early history, children’s museums have not only been educational and fun, but they have also been utilized to share information on topics that are sometimes hard to talk about.” However, the museum lacked specialized knowledge on grief coping strategies. Through consultation with Lori Tschetter and other members of SSM Health’s bereavement team, the partners began to formulate some initial ideas for the event. Inspired by the hero toolkit created by the National Alliance for Children’s Grief, the team proposed “Super Saturday” as its formal name. As Welsch explains, the event’s goal is to help children “find their superpowers”—that is, to recognize “that they have these strengths and skills inside them” that are beneficial in times of grief.

On Super Saturday, the entire museum space is devoted to activities focused on grief and loss; as Welsch puts it, the event is “like the museum on steroids.” While families receiving care at the hospital receive free passes, all are welcome. “All children will go through some sort of loss in their lives,” Welsch notes, adding that the aim of Super Saturday is to offer children and caregivers useful tools and resources they can make use of whenever tragedy strikes.

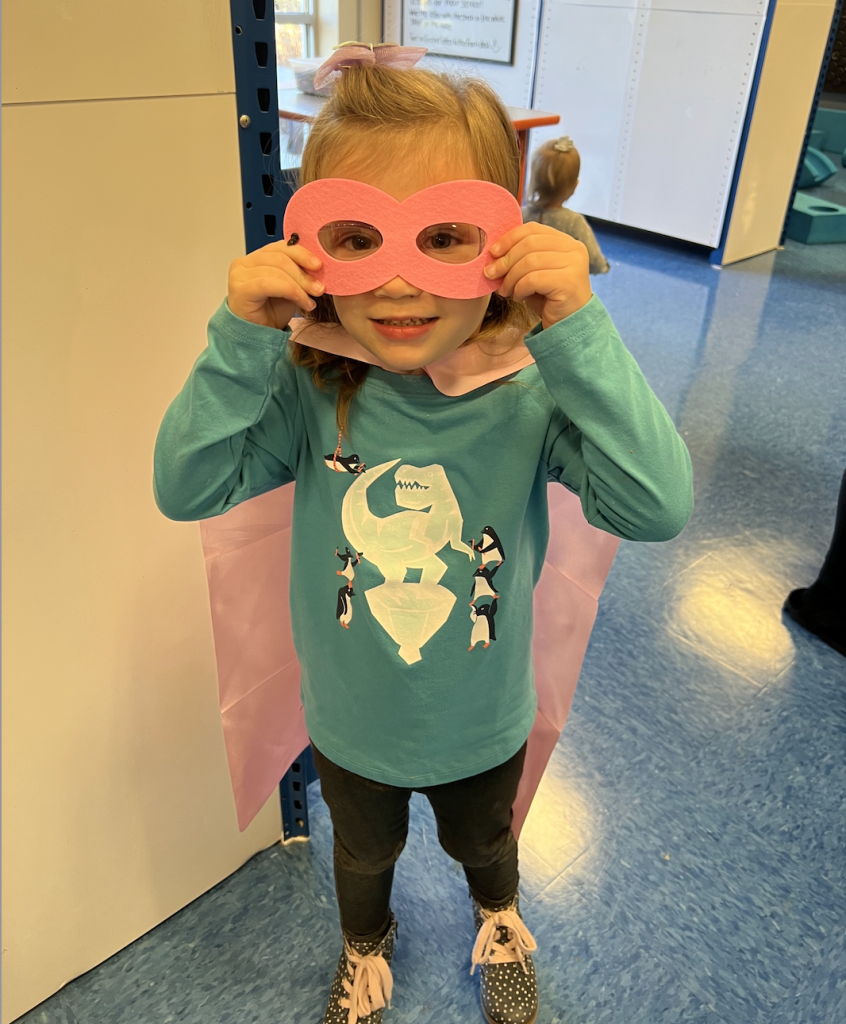

Those who attend Super Saturday receive a cape from the museum. As CEO Andrea Welsch explains it, the goal of the event is to help children “find their superpowers” — to see that “they have these strengths and skills inside them” for helping deal with loss.

Children are invited to come in their Halloween costumes; as an added bit of fun, they get capes from the partners when they arrive. From there, they can participate in any number of activities—all of which are geared toward equipping them with tools, techniques, and resources they can “call on later in life when they may need them.” Activities include:

Along with these individual activities, visitors can also contribute to a collaborative art project near the museum’s lobby. While this is an ongoing project whose themes change every month, in November, visitors are given paper butterfly wings and asked to post a message about “someone special that I’m thinking of.” On Super Saturday, the art board rapidly fills up with butterfly wings, and it serves as “a big photo op” for families.

When the museum first launched Super Saturday, staff were uncertain what the community’s response would be. ”It was a bit of a scary space to be in,” Welsch recalls, explaining that the museum was “a little afraid to be inviting people to a fun event based on a sad topic.” During the run up to that first event, staff wrestled with questions like “how do we even promote this, and what if we are asked questions that are for grief experts, not museum staff?” There was a fear that no one would show up. ”I thought people would be afraid to come because of a perception that we’d be judging them,” Welsch adds.

But that wasn’t the case at all. The community’s response in that first year “blew me away,” Welsch says. Roughly 250 people participated that year, and since then, those numbers have more than doubled. “We’ve had so much success in bringing people out,” Welsch adds, noting that even during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Super Saturday “turned out a huge audience.”

As SSM Health’s Lori Jo Tschetter explains, Super Saturday activities teach children about grief and loss in a “safe, easy way that’s understandable for everyone.”

One of the things that’s made Super Saturday such a success is the fact that it “doesn’t single anyone out.” As the event is open to everyone, it’s impossible to distinguish between children or caregivers in the hospital’s bereavement program and those who aren’t. Children who haven’t yet experienced a significant loss are offered “a light-hearted way to get that conversation going,” Tschetter says. For families actively dealing with loss, Super Saturday offers “a reason to go out and do something together.” Serving a normalizing function, the event teaches those who are actively grieving that “you can have fun and don’t always have to be sad.” It’s because of this that families receiving professional care “always look forward to the event,” Tschetter says.

Welsch and Tschetter agree that Super Saturday’s chief value has to do with how it offers an opportunity to discover valuable resources and practices “in a really fun, very easy sort of way.” As an example of this, the two reflect on the “Faceless Dolls” activity, which has consistently been one of the event’s most popular. “Kids love it because it’s tangible,” Welsch says, adding that it offers a developmentally appropriate way for children to “get their emotions out.” Often, children depict contrasting emotions on the two sides of the doll (for example, one side depicting a happy expression and the other a sad one). By encouraging use of the doll in the home, caregivers can see how their children are feeling at any given moment—which is important, Tschetter explains, given the fact that “kids don’t want to come to you and say ‘this is how I’m feeling.’”

Partnerships are another major contributing factor to the event’s success. The museum has been “so blessed to work with experts from SSM Health, and the hospital volunteers that have facilitated activities with kids,” Welsch says. Prior to launching Super Saturday, she adds, museum staff had “no idea what kinds of activities would be helpful for children going through different kinds of loss.” Now, after ten years, the museum has learned so much from Tschetter and her team that they feel confident in running Super Saturday themselves—which has become necessary on account of the hospital downsizing some of its bereavement services. “They’ve taught us so much,” Welsch says, highlighting how incredible it is that the museum is able to “still offer this awareness and education to the community” even without the hospital’s direct on-site involvement during the event. Other local organizations have also contributed. The cloth dolls that are part of the “Faceless Doll” activity are made by local high school students. Students from the high school’s Key Club and National Honor Societies also often serve as volunteers at the event, helping children complete activities and move throughout the museum.

Running Super Saturday year after year has taught Welsch and Tschetter how perfectly situated children’s museums are for this kind of work. As Tschetter sees it, Super Saturday is in many ways an ideal site for providing grief support. “I can sit and talk to parents all day,” Tschetter says of her work in clinical settings, “but that doesn’t mean they’re going to even understand my grief speech.” By contrast, when attending Super Saturday, families receive information, guidance and support that’s presented in a “safe, easy way that’s understandable for everyone.”

The experience of hosting Super Saturday year after year has taught the museum how important it is to provide a safe, fun environment for learning about loss. “What we’re doing really does matter,” Welsch says.

Over the years, the museum has learned a great deal from its experiences hosting Super Saturday. A key lesson has been the importance of partnerships. “Working as a community is key,” Tschetter says, noting that events like Super Saturday would not be possible without organizations pooling together their respective strengths and resources. Along with this, Welsch says, it’s important to have a varied set of tested, effective activities on hand—and to keep things simple. Having every activity be “big and heavy” can make children feel overwhelmed, she notes, adding that for some stations, all that’s needed are coloring sheets with simple instructions.

The last and perhaps most important lesson is to not be afraid. “Loss is a tough topic,” Welsch acknowledges, and because of this, museums might be apprehensive about hosting activities or sharing resources focused on it. But “people really want this information,” Tschetter observes. Given that desire, the key thing is “just being willing to try.” “All parents want to be great parents, and want to support their kids with the hard stuff,” Welsch observes. “Put those two together and you’ll have an audience that shows up for this kind of programming.”