March 17, 2022 / News & Blog

| This article is part of the “Children’s Museums and Climate Change” issue of Hand to Hand. Click here to read other articles in the issue. |

By Lisa Thompson, Natural History Museum of Utah | University of Utah

A Climate of Hope is the working title we’ve adopted for a new exhibit on climate change under development at the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU). Like our colleagues at natural history and science museums around the world, NHMU is shifting away from an older, more data-driven approach to climate change exhibits (also known as the “doom and gloom” approach—largely focused on the dire nature of the crisis). As our working title suggests, our goal is to create an exhibit that inspires hope and empowers visitors to take meaningful climate action in their communities.

This article highlights a few of the “guiding principles” shaping the content and design of our exhibit that we have learned from research on effective climate communication, consultation with wonderful advisors, front-end evaluation with visitors, and evaluation of a full-scale cardboard prototype of the exhibit. Although our exhibit is not aimed specifically at young children, we hope some of these ideas will be useful in exploring how children’s museums can create hopeful, empowering experiences that support children and families.

Some inherent challenges come with tackling climate change in an exhibit. Even a title mentioning climate change could turn away visitors whose political identity tells them, “This exhibit isn’t for me,” as well as people who are worried the exhibit will add to the anxiety and stress they already feel about climate. In contrast, other audiences may not have strong feelings about climate change or perceive its personal relevance because it seems remote in time and distance, a problem for other people far away in the future.

One key idea that emerged from our initial dive into the rich body of climate communication research was the importance of “side doors.” When tackling a polarized issue like climate change, side doors frame the issue in ways that aren’t clearly marked as belonging to one partisan group. They focus on shared values that resonate across groups with diverse perspectives and create a space for taking action together. Talking with local organizations working on climate solutions and our visitors in a front-end evaluation helped us identify some of the side doors that resonate with Utah audiences.

At the top of the list is Utahn’s deep concern about the impact of the poor air quality in many parts of the state on their health. While the greenhouse gases that cause climate change and the particulates and ozone that damage our health are distinct, they are often emitted by the same sources. For example, focusing on how measures that improve Utah’s air quality can also reduce greenhouse emissions offers a side door to climate action. Other side doors that resonate with our audiences include concern about the decline of Utah’s famous snow that supports our ski industry, a strong tradition of emergency preparedness that could carry over into creating climate resilient communities, and the opportunities for Utah to benefit economically from developing and implementing climate solutions.

The local nature of these side doors reflects another key idea that emerged from our research—the power of telling local stories to make climate change immediate and relevant for our audiences. While melting glaciers and rising sea levels seem remote to many Utahns, stories that demonstrate local climate impacts in relatable ways made a big impression on visitors in our prototype exhibit. For example, one story in the prototype that visitors often discussed illustrated Utah’s warmer, shorter winters with a historic photo of ice skaters on a well-known park pond that rarely freezes today. The prototype also offered visitors a chance to share their own observations of local climate impacts and what they mean for them at a talk-back station.

Stories about the many existing, feasible climate solutions already being implemented in communities around Utah also connected with prototype participants. They expressed excitement, surprise, and pride upon discovering the numerous efforts underway in Utah along with some of the innovative ideas in development. Focusing on solutions is another key principle of effective climate communication. Solutions, after all, offer hope and inspiration. Stories about people implementing effective solutions also serve to counter common misperceptions our visitors expressed in our front-end evaluation—“Nobody is doing anything” and “Solutions don’t exist yet”—which serve to discourage and disempower.

Our front-end evaluation with visitors provided important context for developing our exhibit. When we asked participants how thinking about climate change made them feel, they predominantly expressed discouragement, fear, anger, confusion, and other negative emotions. Their responses reflect the growing number of people who report experiencing climate anxiety or climate grief. However, according to research in psychology, fear and uncertainty can shut down our ability to act.

A growing number of climate communication researchers emphasize the importance of acknowledging the powerful emotions climate change evokes, helping people understand how their emotions impact their ability to act, and emphasizing that taking action can lead to feeling more hopeful. This approach presents hope as a practice to be cultivated, not something you can obtain simply by wishing for it. As Dr. Katharine Hayhoe explains: “Hope doesn’t come to me if I just sit there waiting for it to show up.”

In A Climate of Hope, we are seeking ways to explicitly address the emotional component of climate change and give visitors a chance to share their feelings through an interactive, which will have a therapeutic or cathartic quality. The exhibit will also introduce visitors to the idea of hope as an outcome of action. One idea we are considering is a set of short “TikTok” style videos of community members responding to the prompt, “What gives me hope…” with a description of the action they are taking.

Both the front-end evaluation and exhibit prototype showed that visitors were extremely interested in knowing what actions they could take to reduce climate change. In fact, in the prototype it was clear that visitors expected—almost demanded—to learn about what individual actions they could take in their daily lives in an exhibit about climate change. While individual actions can be a good start, climate science indicates that they aren’t sufficient for addressing a problem that requires systemic change. Plus, placing the onus of addressing climate change on individuals—especially through their consumer choices—fosters “climate guilt” and is inequitable to those who can’t afford those choices.

A Climate of Hope will seek to provide visitors with a different set of tools for taking meaningful action. We envision opening the exhibit with an immersive interactive that engages visitors in imagining a future where humans and nature thrive in a changing world. Many visions of the future related to climate change in our culture are dystopian if not apocalyptic. Several climate communication scholars are emphasizing the need for new cultural stories that help us know what we’re aiming for and envision paths to getting there. Even the very low-tech version of the interactive we created for the prototype was compelling for visitors, and many reflected on the content of the videos during their wrap-up discussion.

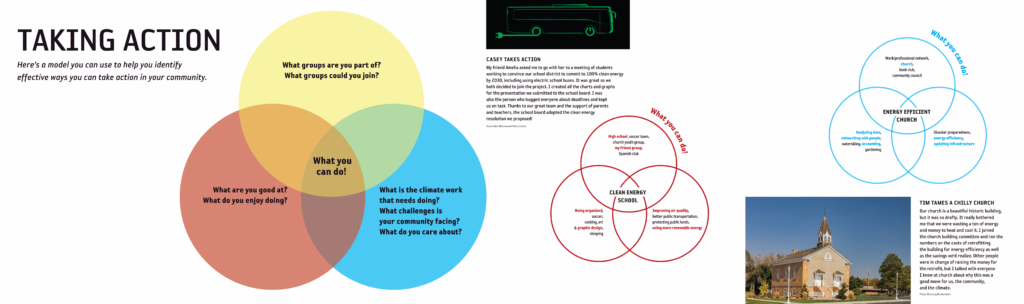

The prototype also included a Venn diagram that provided visitors a framework for thinking about how they could take action at the community level—a level at which actions have more possibility of affecting systems change. Our goal is to encourage visitors to take the next step beyond individual actions to actions in their networks that still feel personally relevant and achievable. The three circles of the Venn diagram contained a set of questions visitors could answer to identify ways they could act:

We realized that this framework would be a significant shift from the messages focused on individual actions most visitors are accustomed to receiving. We were pleasantly surprised that many prototype participants called others over to the Venn diagram to discuss it and mentioned it in their conversation with evaluators.

The prototype also included a Venn diagram that provided visitors a framework for thinking about how they could take action at the community level—a level at which actions have more possibility of affecting systems change. Our goal is to encourage visitors to take the next step beyond individual actions to actions in their networks that still feel personally relevant and achievable. Image credit: Dawn Renee Farkas Prasad

One individual-level action the exhibit will highlight is talking about climate change with family and friends—not to persuade or debate, but to listen and share. Surveys from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication indicate that more than 70 percent of Americans are worried about climate change, but only 35 percent talk about climate change even occasionally. Talking about climate change is critical for processing our emotions, imagining and telling new stories about our future, and finding and building networks for community action. Climate communicators have developed great resources outlining how to have a constructive climate conversation.

While visiting the prototype, several parents asked for resources on talking with their children about climate change. We are just beginning the process of developing family resources for the exhibit. We are considering the approach of encouraging families to focus on building the social and emotional skills we all need for being resilient, such as empathy, talking about our feelings (especially when we’re worried), and working together to tackle big problems. Because children’s museums excel at creating experiences that foster the development the social and emotional skills for resiliency, they are already doing important climate solutions work.

Other climate communication approaches align well with the strengths of children’s museums and could even be worked into existing exhibits and programs. For example, stories about local people and organizations working to implement climate solutions fit naturally with exhibits about the people who make our communities safer, healthier, and stronger. Activities that invite children and their caregivers to imagine the future of their community could include challenges for designing new kinds of climate adaptations. And children’s museum could host activities or partner with other organizations to connect families with opportunities to take action in their community, such as planting trees or community gardening.

Children’s museums are well-situated to play an important role in building a climate of hope that empowers children and their caregivers to take meaningful climate action and develop the resilience and empathy we’ll need to navigate climate change. We’re excited to see how you do it.

Lisa Thompson has worked as an exhibit developer at the Natural History Museum of Utah at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City since 2013. Prior to this, she managed Public Programs teams at NHMU and Discovery Gateway Children’s Museum in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Building A Climate of Hope Resource ListA short and by-no-means-comprehensive list of climate communication resources to get you started. Organizations with great research and tools:

Voices for hope:

Climate Communication in action: |