August 23, 2022 / News & Blog

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 5.3, the third report in the fifth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

This ACM Trends Report delves into the topic of trust, which is particularly important as museums reach out to new audiences with activities such as virtual programming. Knology researcher John Voiklis shares what research suggests about the nature of trust and its impact on the relationship between a museum and its audience(s).

Virtual programming became an unplanned necessity when children’s museums had to close their doors to the public during the pandemic. Nevertheless, it began to fulfill a long-sought goal of children’s museums: reaching previously unreachable audiences.

This benefit was cited by participants in the surveys that were reported in Volume 4 of the ACM Trends Report series, and by participants in the first annual discussion forum hosted by Knology and Association of Children’s Museums (see ACM Trends Report 5.1). During the forum, participants talked about using virtual programs to cultivate trusting relationships with new audiences.

This ACM Trends Report differentiates between two types of trust identified by social scientists: identity-based trust and experience-based trust (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, 1998). It reviews evidence from a large-scale study Knology conducted with institutions that share audiences with children’s museums and play a similar role in the social, emotional, and cognitive development of children: zoos and aquariums. The study shows the particular importance of experience-based trust in building trusting relationships with a broad audience. Lastly, the report explores how children’s museums might apply what Knology learned about experience-based trust to outreach efforts such as virtual programming, focusing on two facets: Reliability and Benevolence.

Trust ranks as a major concern in the museum field (Museums and Trust 2021). Moreover, it plays a foundational role in all human relations. The anthropological and psychological literature makes it clear that without help from others, people cannot meet their material, emotional, and intellectual needs (Tomasello & Gonzalez-Cabrera, 2017). Trust is how people manage the risks associated with such high levels of interdependence (Cvetkovich & Lofstedt, 2013).

Almost every scholarly field has developed one or more theories of trust. This report will introduce two consensus varieties: identity-based trust and experience- based trust (Rousseau et al., 1998), focusing on the latter.

Sometimes, people choose to trust those with whom they share some kind of identity or affinity. For example, as a research psychologist, I tend to seek career advice from other research psychologists. This is identity-based trust. At many organizations, the marketing department manages identity-based trust by convincing people to see the organization as a likeable friend. For example, a children’s museum might market itself as a fun place where families feel welcome.

More often, people choose to trust those whom prior experience has shown are trustworthy; this is experience- based trust. Research shows that whether people are judging another person, an organization, or even a robot, they use the same five criteria when conferring experience-based trust: Competence, Reliability, Sincerity, Integrity, and Benevolence.

For example, I trust my hair stylist because she gives me great haircuts (competence) on every occasion (reliability); she is transparent about pricing (sincerity), which is consistent for everyone (integrity); and she both asks after my wellbeing and actively listens to my responses (benevolence). This report will look most closely at Reliability and Benevolence (see section Trust in Children’s Museums).

First, it is useful to summarize some of what Knology has already learned about trust from zoos and aquariums.

While zoos and aquariums are different institutions than children’s museums, all three play a role in the social, emotional, and cognitive development of children.

Further, all three institutions work to build trust as both mission-based organizations that serve their audiences (at least in part) through publicly accessible facilities.

Zoos and aquariums work to promote the conservation of wildlife and wild places. Typically, they rely on identity- based trust to gauge the credibility of their conservation messages: to learn whether their audiences believe their messages they instead ask whether those audiences like them (favorability) and feel attached (affinity) to them as places. This approach is not wrong, but it is incomplete. Although the conservation mission extends far beyond their facilities, people decide whether they trust in the institution’s conservation mission based on what the experience firsthand when visiting and what they hear about through their social networks

Theories of persuasion posit a much larger role for the criteria of experience-based trust (trustworthiness) in deciding whether to believe a message about conservation or any topic.

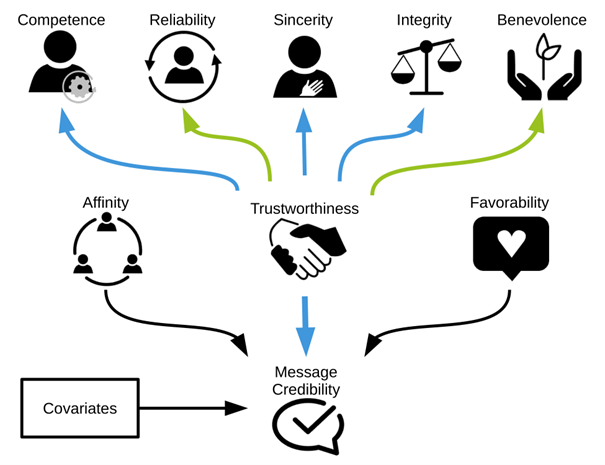

Figure 1. Model of how trust contributes to message credibility. Blue and green arrows show the contributions of experience- based trust. This report pays special attention to the contributions of the green arrows.

Figure 1 shows how the criteria of the two varieties of trust fuse into “epistemic authority”—i.e., whether people see you as a thought leader. The icons represent collections of behaviors the public judges when deciding whether to trust a potential thought leader. The arrows show the influence of epistemic authority on whether people believe the potential thought leader, i.e., believing the conservation messages that zoos and aquariums offer as potential conservation leaders.

Knology worked with zoos and aquariums to identify nearly one hundred behaviors that sampled every aspect of daily operations and mission-related work, including caring for animals, interacting with visitors and the local community, supporting staff, managing their finances, etc. (Voiklis, Gupta, Rank, et al., In Press).

We might call this activity “what is your trust fall?” In identifying these behaviors, Knology was asking zoos and aquariums to imagine each one as a piece of evidence for why members of the public should take the risk of trusting them. Two thousand people from around the U.S. participated in two surveys to assess the importance of these behaviors and how well zoos and aquariums performed them.

The results matched the theory: trustworthiness, with its five experience-based criteria, was the strongest predictor of message credibility. Identity-based trust criteria also mattered, but more so for specialized publics: For example, those who regularly sought out conservation news and likely identified as conservationists.

These findings from Knology on zoos and aquariums offer insights for the children’s museum field. Of course, children’s museums have a distinct trust profile that reflects their focus on children rather than conservation.

Further research is required to identify the key reasons behind children’s museums’ message credibility, as detailed with zoos and aquariums above.

Nevertheless, museum professionals can run an activity akin to the “what is your trust fall?” exercise. They can identify behaviors that provide the evidence their audiences need to assess trustworthiness. Virtual programming can provide evidence for almost every criterion of trustworthiness. Here, we focus on two criteria—Reliability and Benevolence—that audiences are likely to use when judging the trustworthiness of a children’s museum with which they are newly acquainted.

Children’s museums have long sought to reach audiences who cannot visit their facilities due to geographical distance and/or costs. Virtual programs, originally intended as an emergency response to the pandemic, help accomplish that goal. Continuing to produce virtual programming may tax resources for some museums, making these programs unfeasible. However, museums interested in sustaining virtual programming can use it as a way to cultivate the museum’s reputation for reliability and build trust with new audiences.

Producing virtual programming can also serve as evidence of goodwill for audiences who cannot otherwise access the children’s museum. Again, continuing to offer consistent virtual programming would further cultivate the museum’s reputation for benevolence.

Market research (e.g., Dilenschneider, 2020) shows people avoid museums after a negative experience, including a seeming “bait and switch” in programming. It is possible to repair a breach of benevolence (Xie & Peng, 2009), but the process is slow and resource intensive.

Research shows that trust is crucial to successful engagement by public institutions, although much work remains to be done on the specific trust profile of children’s museums. Museums can get a head start by assessing their exhibits and programs—including virtual programming—from the perspective of their audiences. Museums can ask what does this exhibit or program reveal about my Competence, Reliability, Sincerity, Integrity, and Benevolence? Research can then test whether audiences agree when deciding whether they trust children’s museums and believe their messages.

Cvetkovich, G., & Lofstedt, R. E. (2013). Social Trust and the Management of Risk. Routledge.

Dilenschneider, C. (2020, June 24). Why People Say They Won’t Visit Cultural Entities, COVID-19 Aside (DATA). Impacts Experience. https://www.colleendilen.com/2020/06/24/why-people-say-they-wont-visit-cultural-entities-covd-19-aside-data/

Field, S., Fraser, J., Thomas, U.G., Voiklis, J., & ACM Staff (2022). The Expanding Role of Virtual Programming in Children’s Museums. ACM Trends 5(1). Knology & Association of Children’s Museums.

Museums and Trust 2021. (2021, September 21). American Association of Museums. https://www.aam-us.org/2021/09/30/museums-and-trust-2021/

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so Different after All: A Cross-Discipline View of Trust. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404.

Tomasello, M., & Gonzalez-Cabrera, I. (2017). The Role of Ontogeny in the Evolution of Human Cooperation. Human Nature, 28(3), 274–288.

Voiklis, J., Gupta, R., Rank, S. J., Dwyer, J. T., Fraser, J. R., and Thomas,

G. (In Press). Believing zoos and aquariums as conservation informants. Zoos & Aquariums in the Public Mind. Springer Nature.

Xie, Y., & Peng, S. (2009). How to repair customer trust after negative publicity: The roles of competence, integrity, benevolence, and forgiveness. Psychology & Marketing, 26(7), 572–589.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.