Data from this report was collected through a search of available literature. The research was supported by funding from the New York Life Foundation.

This ACM Trends report looks at how children’s museums can harness the therapeutic power of play to benefit the many bereaved children who walk through their doors every day. It also highlights two other actions children’s museums can take to provide for the needs of the bereaved: capacity building and resource sharing. The guidance offered here builds on Trends Report 8.1, which surveyed recent literature on bereaved children’s needs and the kinds of experiences that can help them overcome the grief associated with the death of a loved one. By leveraging the therapeutic power of play, building their own capacities for recognizing and responding to loss, and mobilizing existing community resources, children’s museums can contribute to the growth of new, community-driven modes of caring for the bereaved.

Data from this report was collected through a search of available literature. The research was supported by funding from the New York Life Foundation.

Experiencing the death of a loved one is a distressingly common reality for children. The most recent data from Judi’s House (an organization dedicated to providing comprehensive support services to grieving children and their families) indicates that one in twelve children in the US will lose either a parent or a sibling by the time they turn eighteen (Judi’s House, 2024). Rates of bereavement are even higher for children in racially and ethnically minoritized groups, and for those living in socioeconomically marginalized families.

Children’s museums can help facilitate bereaved children’s grieving processes. In support of this goal, this Trends report presents key research findings from the literature on bereaved children. As the first in a new series focusing on childhood bereavement, this report offers a foundation for bereavement interventions by explaining key concepts, highlighting bereaved children’s needs, and sharing general information on the kinds of experiences and supports that can help children overcome the grief associated with the death of a loved one

Data for this report was collected through a search of available literature. This research was supported by the Institute for Museum and Library Services.

The world is designed for mobile media, including smartphones and tablets, and young children are already using these tools in a range of settings. This ACM Trends report summarizes what is currently known about the ubiquity of mobile media in young children’s lives, including the caregivers’ decisions about their children’s use. We end with a consideration of how children’s museums might take advantage of current uses. This report builds on ACM Trends 7.1, which explored general principles of digital media that supports powerful learning.

This report is based on a review of the research literature. We read dozens of empirical reports and peer-reviewed articles about early childhood media use, from university researchers and organizations like Sesame Workshop, PBS KIDS, Common Sense Media, the National Association for the Education of Young Children, the Fred Rogers Institute, and the American Association of Pediatrics. One challenge in reviewing this research is a lack of consensus definitions. That means we took a broad view and included any research about media content for young children delivered over the internet, from synchronous digital programming and live video calls to games and apps.

Data for this report was collected through a review of existing literature. This research was supported by the Institute for Museum and Library Services.

When designed well, virtual programming and online experiences can facilitate meaningful learning moments in early childhood.

This ACM Trends report focuses on these digital media as one educational tool in the museum toolkit. Several well-regarded early childhood organizations have endorsed particular uses of media even for very young children, and we explore the principles and the research behind them before turning to criteria that can help identify when media is the right tool. ACM Trends 7.2 will build on this report by looking at empirical questions that must inform design: how often children use media, which children use media, and where children use media.

This Trends report reviews the research findings and concludes with practical advice for children’s museums seeking to design meaningful digital media experiences for young children.

Data for this report comes from two surveys. That pertaining to children’s museums’ collaborations with libraries was collected through the Spring 2023 ACM Member Collaborations survey. The dataset contains information from 59 member institutions. Data on library collaborations with museums was collected through a NILPPA survey of US libraries conducted in 2022. This dataset contains information from 314 libraries. Research for both of these projects is supported by the Institute for Museum and Library Services (Grant #s: MG-251839-

OMS-22; MG-80-19-0042-19; LG-250153-OLS-21).

Libraries and museums have a shared mission as sites of informal learning.

Both museums and libraries are in the process of expanding the ways they serve their communities, going beyond informal learning to become sites for convening, health and wellness, and other community needs. As their roles change, there are new opportunities for museum-library partnerships. To help children’s museums leverage their existing library partnerships (or form new ones) in support of newly emerging goals, this Trends Report offers a library centered perspective on what makes partnerships effective. What are libraries looking for in a prospective community partner? What do they value in their collaborative relationships? And what are new ways children’s museums can work with libraries to support broader community goals?

The survey also offered insights into the goals children’s museums are pursuing through collaboration. Though varying considerably, museums’ collaborative goals are connected to three broadly shared aims: (1) healing; (2) learning; (3) community. In what follows, we discuss how these findings can help children’s museums understand, approach, and evaluate collaborative work. Our hope is that sharing this information will not only stimulate dialogue around collaboration and partnership, but also help children’s museum leaders plan new collaborative programs and begin the process of building relationships with new partners.

To address these questions, we explore findings from two recent IMLS-funded field-wide surveys: (1) the Spring 2023 ACM Member Collaborations Survey (whose results we discussed in ACM Trends Report 6.3); (2) a 2022 survey conducted by Knology and the American Library Association’s Public Programs Office (ALA PPO) as part of an IMLS-funded project called “National Impact of Library Public Programs Assessment” (NILPPA.org). Both surveys included questions about collaborative programming, and their results offer insights into how libraries and children’s museums can expand and strengthen their partnerships in support of shared institutional and community goals.

Data for this report comes from two surveys. That pertaining to children’s museums’ collaborations with libraries was collected through the Spring 2023 ACM Member Collaborations survey. The dataset contains information from 59 member institutions. Data on library collaborations with museums was collected through a NILPPA survey of US libraries conducted in 2022. This dataset contains information from 314 libraries. Research for both of these projects is supported by the Institute for Museum and Library Services (Grant #s: MG-251839-

OMS-22; MG-80-19-0042-19; LG-250153-OLS-21).

Libraries and museums have a shared mission as sites of informal learning.

Both museums and libraries are in the process of expanding the ways they serve their communities, going beyond informal learning to become sites for convening, health and wellness, and other community needs. As their roles change, there are new opportunities for museum-library partnerships. To help children’s museums leverage their existing library partnerships (or form new ones) in support of newly emerging goals, this Trends Report offers a library centered perspective on what makes partnerships effective. What are libraries looking for in a prospective community partner? What do they value in their collaborative relationships? And what are new ways children’s museums can work with libraries to support broader community goals?

The survey also offered insights into the goals children’s museums are pursuing through collaboration. Though varying considerably, museums’ collaborative goals are connected to three broadly shared aims: (1) healing; (2) learning; (3) community. In what follows, we discuss how these findings can help children’s museums understand, approach, and evaluate collaborative work. Our hope is that sharing this information will not only stimulate dialogue around collaboration and partnership, but also help children’s museum leaders plan new collaborative programs and begin the process of building relationships with new partners.

To address these questions, we explore findings from two recent IMLS-funded field-wide surveys: (1) the Spring 2023 ACM Member Collaborations Survey (whose results we discussed in ACM Trends Report 6.3); (2) a 2022 survey conducted by Knology and the American Library Association’s Public Programs Office (ALA PPO) as part of an IMLS-funded project called “National Impact of Library Public Programs Assessment” (NILPPA.org). Both surveys included questions about collaborative programming, and their results offer insights into how libraries and children’s museums can expand and strengthen their partnerships in support of shared institutional and community goals.

Data for this report was collected through a Spring 2023 ACM member survey on collaborations. The dataset contains information from 59 member institutions. Previous pandemic-era survey data on collaborations conducted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic supported instrument sevelopment. This research was supported by the Institute for Museum and Library Services

Children’s museums are part of an ecosystem of community services designed to enrich children’s lives through the provision of informal learning experiences. That ecosystem functions best when the various institutions comprising it are working together, sharing their resources and capabilities to more effectively connect with and serve their audiences.

We saw evidence of this during the height of the pandemic. As reported in Trends Report #4.8, #4.10, and #4.11, children’s museums adapted to the constraints imposed by COVID-19 by forging partnerships with new collaborators and expanding existing collaborations. The public health crisis inspired children’s museums to join forces with an incredibly diverse array of community organizations, including formal educational institutions and health and social service providers. These collaborations led not only to new

programs, but also to broader conceptions of community service and fresh insights into how children’s museums can deliver on their mission.

This edition of the ACM Trends series provides an update on our pandemic-era research. As of Spring 2023, 95% of children’s museums have re-opened their doors, and to understand how this transition is impacting their collaborative work, we administered a survey focused explicitly on this topic. Fifty-nine ACM members completed this survey. Their responses indicate that the resumption of in-person activities has not diminished children’s museums’ eagerness for collaborating with partners across a wide range of service vectors. Moreover, just as was true at COVID-19’s peak, programs focused on health and wellbeing remain a core part of their collaborative efforts.

The survey also offered insights into the goals children’s museums are pursuing through collaboration. Though varying considerably, museums’ collaborative goals are connected to three broadly shared aims: (1) healing; (2) learning; (3) community. In what follows, we discuss how these findings can help children’s museums understand, approach, and evaluate collaborative work. Our hope is that sharing this information will not only stimulate dialogue around collaboration and partnership, but also help children’s museum leaders plan new collaborative programs and begin the process of building relationships with new partners.

Data for this report was drawn from publicly available IRS Form 990s posted on Candid and the ProPublica nonprofit look-up tools. Supplemental data was collected through the Spring 2022 ACM member survey.

Since 2019, ACM and Knology have been working to create a data-based resource geared toward helping children’s museums learn about emerging trends across the field. The result of our efforts is the ACM Trends Data Hub—an online portal that visualizes trends in museum attendance, income, expenses, and staffing from 2016 to the present. Created with data from ACM member surveys and the publicly available US tax Form 990s that all US non-profits are required to complete every year, the Data Hub displays individual museum information that can be filtered by size, ACM member level, US region, and by city and state. As a management tool, the Data Hub allows children’s museums to monitor their performance across the aforementioned indicators, and to compare this to other institutions and sector-wide trends. Though at present the Data Hub only features US-based museums, the ACM Trends team will aim to incorporate data from museums outside the US in the future.

To facilitate the Data Hub’s use, this ACM Trends Report highlights one of its most important features: the use of median values to express sector-wide trends. Whenever highlighting sectoral averages in attendance, income, expenses, or staffing, the Data Hub uses median values. This is because medians are often preferrable to other ways of computing averages (like the statistical mean or mode) when it comes to museum data.

In this report, we explain why medians are so often the best way of identifying trends and tendencies for museums. Using examples from our research, we illustrate how museum data is often distorted by statistical outliers that make mean values less representative of the tendencies that most museums might see. This is the reason that medians offer a more accurate reflection of what a “typical” children’s museum should expect in their context.

By understanding what median values suggest, children’s museums will be better positioned to use the Data Hub to understand their financial positions, to support accountability to their funders based on industry norms in comparison to local conditions, and to assess performance compared to their peers.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 6.1, the first report in the sixth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

Members are the lifeblood of many children’s museums. They are loyal patrons who trust museums to provide playful learning opportunities for their children, often complementing trips to the zoo or aquarium. But when children “age out,” families may turn to other cultural institutions and start to reconsider the value of their membership. Understanding value seekers’ calculations can help children’s museums cultivate trust through transparency.

In this Trends report, we look at what membership pricing and attendance data can tell us about children’s museums. We focus on what museums might want to think about when attempting to stabilize their membership base, and on how to forge trusting relationships with prospective members.

National data related to membership pricing has been of particular interest to the ACM leadership community in recent years, especially as it relates to post-pandemic operations. Prompted by a specific request from an ACM member, this report contributes to these ongoing discussions. We used data from the Spring 2022 targeted ACM member survey and collected additional information from member museum websites. We developed a dataset from 90 children’s museums to see if there were differences in membership costs between small, medium, and large museums. We also compared admission prices across these categories and calculated a “pay less” point—that is, the number of times a family of four would need to visit in order to make the

purchase of an annual membership a cost-saving act.

Our analysis yielded two main findings. First, even though admission prices and membership costs are highest for large museums, the number of single visits needed by a family of four to “pay less” is lower for these museums than it is for their small and medium-sized counterparts. Second, we confirmed that admission prices and membership costs tend to rise in parallel, which means that even though base admission prices may be determined based on local cost of living concerns, ACM members can still compare their rates to other children’s museums, Taken together, these findings can help children’s museums determine how to align pricing decisions with the needs and interests of value-seeking visitors—that is, those who purchase memberships based on a calculation of savings.

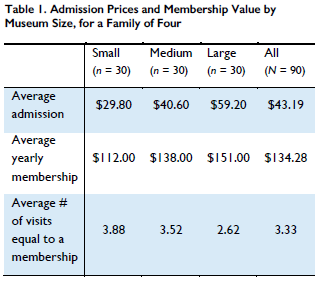

In Spring 2022, the ACM Trends Team circulated a survey to ACM member institutions requesting data on attendance, admission prices, membership costs, and other operations. After supplementing this data with information gleaned from member websites in August 2022, we assembled a dataset of 90 museums (30 of each size). We summarize the data in Table 1 below.

Table 1 compares admission and membership prices for a family of four at small, medium, and large museums. Admission prices are based on the general admission price for adults and children. When prices for adults and children were different, a family of four was calculated with two adults and two children.

We calculated these figures for a two-adult, two-child family on account of current US Census data (which shows that the average US family contains 3.13 people), and because this aligns with demographic research showing that a plurality of mothers in the US today report having two children (Pew Research Center, 2015).

The bottom row in Table 1 presents the average number of times a family of four would need to pay admission before achieving cost-savings through a membership purchase. The fourth column illustrates the mean cost across all size categories—which is an appropriate way to calculate averages in a dataset like this one, as it contains few outliers.

Clearly, the larger the museum, the higher the membership and admission costs for a family of four. Nevertheless, the number of visits needed for a valueseeker to “pay less” for multiple visits through a membership is lower (2.62) for large museums than for their small (3.88) and medium-sized (3.52) counterparts.

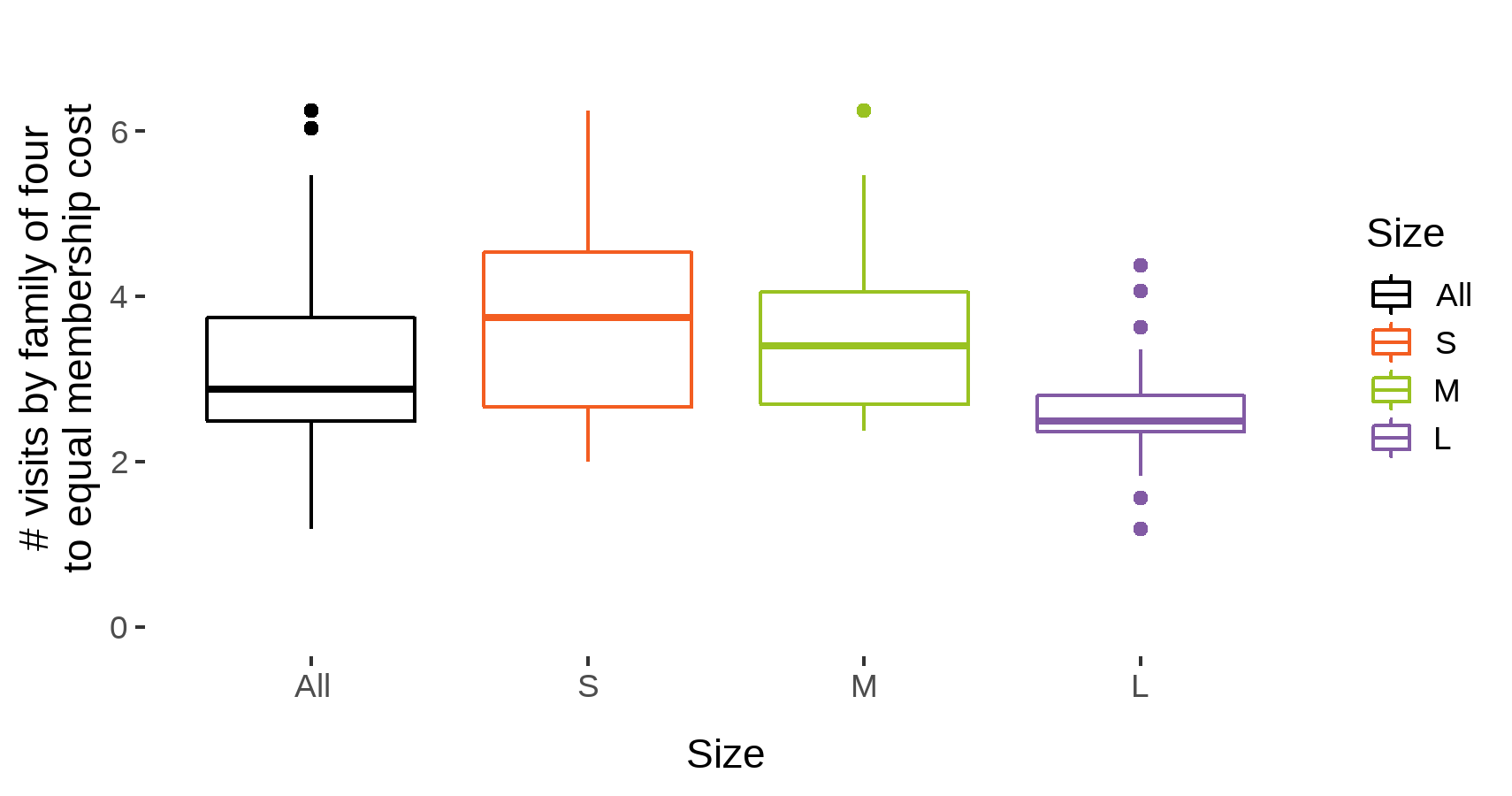

Figure 1 presents data from the bottom row of Table 1 as a “box and whiskers” plot. To create this, we “normalized” pricing data to show membership costs (for a family of four) as a multiple of admission costs for each children’s museum. The “box” part of the plot illustrates the middle half of the data (in other words, where 15 of the 30 museums in each size category sit), while the “whiskers” indicate those museums where prices are higher or lower than their peers.

When a museum stands alone compared to others, the box and whiskers plot expresses this with dots, considered outliers. When multiple museums lie in the same range, this is indicated by a line placed above the box. The line in the middle of the box illustrates the median, or the exact middle of all of the data in that category. We can see from those lines that medium-sized and small museums tend to be near one another. To see how many visits a family of four would need to make before generating savings through the purchase of a membership, look at the Y-axis, which plots the ratio of membership costs to visit price. This data can be used as a foundation for making decisions about membership pricing, especially in connection with data on premiums.

We also collected data on additional benefits provided with museum memberships—for example, discounts for rentals or birthday parties (n = 60), member-only events (n = 53), and reciprocal admission to other ACM (n = 24) or ASTC (n = 13) member institutions. Most museums offer these in some form; 8 out of 10 small museums, 9 out of 10 medium-sized museums, and all large museums indicated additional membership benefits. The total number of additional benefits did not appear to be related to a higher value of memberships.

One benefit, however, did have a significant effect on “trips to match cost.” Offering a discount on space rentals, after accounting for museum size, was related to higher membership costs. Though some have suggested that early access or discounts on summer camps are perceived as an incentive for families who can afford summer camp experiences, our analysis did not provide any evidence that the benefit is related to higher or lower membership prices.

We also looked at a subset of the data from fifty-one museums (1 small, 15 medium-sized, 20 large, and 3 yet to be classified) who responded to the Spring 2022 ACM member survey and provided information on annual attendance and member attendance from FY2016 to FY2021. Looking at the data, we can determine historical trends in museum attendance, and also calculate the proportion of overall attendance consisting of museum members.

Prior to the pandemic, in FY2016 through FY2019, the median number of memberships purchased per year for these museums was between 2200 and 3000. In FY2020 and FY2021, this value dropped to 968 & 1188 memberships purchased, respectively. Along with this decline, the proportion of overall visitors who were

museum members decreased roughly 6% in 2021 for these museums. While these museums are just a portion of the overall ACM field, the decline likely reflects the impact of the pandemic across the sector.

People purchase museum memberships for different reasons. These purchases provide a reason for frequent visits—which not only benefits children but can also help museum leaders advocate for children’s access to the healthy spaces of learning and discovery children’s museums provide. For some, a membership is a valueseeking purchase, one made through a consideration of future costs, benefits, and savings. Value-seekers become members because they want museum-going to be a regular part of their children’s lives. These pricing data tell us that museums anticipate four visits a year by their value-seeking members, setting prices that justify at least four or more visits in a membership year.

For others, purchasing a membership may not be driven by monetary concerns. They may simply want to invest in an institution that is doing good work, or to support a local institution that is good for children. Some individuals may purchase memberships to build social capital, because they want to support an organization whose values they identify with, and because they want their membership to reflect something about who they are. They may also become members because they want to encourage their grandchildren, nephews, nieces, or other relatives to visit them, or because they want to provide gifts to families with children. These “affinity members” may also care less about free admission than about membership perks, premiums, or about symbolic value—for example, discounts on birthdays or group tours, reciprocal admission at other ACM member museums or other cultural institutions, access to priority registration, exclusive programs, or behind-the-scenes content.

In other words, value is a complex, multidimensional thing. When thinking about those who see the primary value of a museum as its price, children’s museum leaders can also consider how decisions related to pricing might impact the perceived trustworthiness of their institutions. As ACM Trends #5.3 discussed, in order to cultivate public trust, museums need to demonstrate competence, reliability, sincerity, integrity, and benevolence. During the height of the pandemic, many museums demonstrated benevolence through refunds or by pro-rating existing memberships. At present, some museums are considering increased fees to recoup pandemic-related monetary losses. Doing so may risk the trust built through the pandemic, especially as cost-of-living increases may make more members value-seekers.

Data for this report was collected through: (1) an online survey distributed by ACM in April 2022; (2) a review of ACM member institutions’ websites. This dataset contains information from 90 current ACM member museums.

Our analysis used the size categories developed in ACM Trends Reports #1.1 and #1.7. We use these categories because institutional size predicts a range of outcomes for children’s museums. We note that museums offer many types of reduced priced tickets or free admission, and some unique premiums that were not used in this analysis.

Voiklis, J. (2022). Key Concepts: Trust. ACM Trends 5(3). Livingston, G. (2015). “Childlessness Falls, Family Size Grows Among Highly Education Women.” Pew Research Center.

US Census Bureau (2021). America’s Families and Living Arrangements. Retrieved from: [https://www.statista.com/statistics/183657/average-sizeof-

a-family-in-the-us/]

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 5.4, the fourth report in the fifth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

For this ACM Trends Report, we invited staff from National Children’s Museum in Washington, DC, to write about their experiences with virtual programming during COVID-19. Staff from the museum participated in the October 2021 discussion forum focused on virtual programming (See ACM Trends Report 5.1 for details).

After seventeen years without a permanent home in Washington, DC, National Children’s Museum (NCM) reopened as a science, technology, engineering, arts, and math (STEAM) focused institution on February 24, 2020. Eighteen days later, the Museum temporarily closed as a precaution against COVID-19, and committed to providing families and educators with free, meaningful experiences at home. When the institution reopened, NCM continued to offer virtual programming for children under twelve and their families, garnering more than three million impressions to date.

While preparing to reopen, NCM conducted a survey to better understand the community’s engagement with the museum, including its virtual offerings. Fifty percent of respondents indicated they would be likely or very likely to engage with virtual offerings once NCM opened. Although the virtual offerings were initially developed in response to a need created by the pandemic, they are now part of the museum’s ongoing programmatic strategy.

This ACM Trends Report describes the survey items related to virtual programs and the current “evergreen” programming that will be retained based on these data.

When NCM reopened to in-person visits in September 2021, it began complementing its on-site programming with the on-demand resources developed during the pandemic. As NCM looks to the future, staff are committed to maintaining, and in some cases, expanding the museum’s virtual offerings. All of the virtual experiences created during NCM’s pandemic closure are fully aligned with its mission and continue to be essential to its ability to promote its mission to audiences locally and abroad.

Between March and May 2020, NCM produced free STEAM videos that premiered seven days a week on its social platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter). Funded by Booz Allen Hamilton, the series called “STEAMwork” featured experiments, projects, design + build challenges, story times, and demonstrations.

These videos and accompanying resources were made available free-of-charge on NCM’s website and continue to be featured as “STEAM At Home” opportunities in the museum’s newsletter. Staff also send the videos to educators as a post field trip resource for continued learning.

One NCM exhibit that was successfully adapted is its Climate Action Headquarters. In the pre-pandemic era visitors had participated in monthly missions and climate challenges. The virtual format introduced during the pandemic allowed visitors to determine their own climate action hero persona by answering a playful online quiz. This virtual version is available as part of NCM’s STEAMwork series. At this writing, NCM staff anticipate producing additional STEAMwork videos and related resources with ties to curriculum standards to promote classroom use.

With funding from GEICO and The Akamai Foundation, NCM launched the STEAM Daydream with National Children’s Museum podcast in June 2020 to provide tailored content to young audiences.

Staff engaged 3rd– to 5th-graders as interviewers. The first season had 18 episodes on critical, timely issues. Each episode allowed young learners to hear from STEAM experts, ask questions, and understand the world around them. Topics included:

• What children want to know about the COVID-19 vaccine with Dr. Roberta DeBiasi, the Chief of Infectious Diseases at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, DC,

• The wonder of animation with Dave Cunningham, Supervising Director of Nickelodeon’s SpongeBob SquarePants.

The Museum’s podcast, featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Vox, was streamed 5,000+ times, with 15% international listenership for the first season. In 2022, NCM began production for the second season of the podcast for debut in the fall, followed by an assessment to determine the feasibility of a third season.

NCM also developed two 20-minute virtual field trip videos based on in-person offerings. These virtual trips were offered to educators and families free of charge. Both virtual field trips are aligned with Common Core State Standards and Next Generation Science Standards. So far, the videos have been requested by thousands of educators across all 50 states.

The first video, “Head in the Clouds,” prompts budding young scientists to observe and identify different types of clouds. When this video was released in May 2020, the museum received 475 initial requests for it from educators and caregivers. Of those 475 requests, 285 were from educators, who almost universally expressed interest in having their class participate in virtual extension sessions related to the video.

This demand enabled the museum to secure funding from a media company to develop a second video, “Climate Action Heroes.” This video explored the difference between weather and climate and introduces learners to seven real-life climate action heroes from across the country.

To extend learning beyond the videos, NCM has offered classroom teachers the opportunity to sign up for “live virtual extension sessions’’ with museum educators. These hour-long sessions, held over platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams, help youth in formal classroom settings delve deeper into complementary content, participate in virtual activities, and ask museum educators questions.

Grant-funding through the end of 2021 offset the fee-based model for local Title 1 schools to book the sessions at no cost. Between May 2020 and June 2021, NCM fielded requests from 1,401 educators interested in live classroom sessions. Overall, NCM received 2,382 overall requests for access to the “Head in the Clouds” and “Climate Action Heroes” videos.

At this writing, staff plan to focus on content designed specifically for 3rd to 5th grade, which make up the majority of onsite field trips at the museum. Staff believe that this audience will be best served through live virtual field trips led by museum educators.

Based on the scale of these programs, NCM added a dedicated second full time educator to focus on teaching live extension sessions. The internal analysis also confirmed the museum will require dedicated space for a virtual field trip studio to allow educators the privacy and technical setup to teach effectively.

Lastly, the team recognized that programming developed during COVID tended to be longer than newer audiences anticipate. They concluded that offering shorter, fee-based classes, as well as promoting live virtual field trips to a national audience may be an effective use of resources.

NCM shared a re-opening survey through their newsletter, which had nearly 10,000 subscribers at the time of distribution. The 316 returned surveys translate to a (roughly) 3% response rate.

The survey asked two questions on virtual programming:

• During National Children’s Museum’s temporary in-person closure, did you use any of the museum’s digital offerings? If so, please check all that apply.

• How likely are you to continue to use–or begin to use–the museum’s digital offerings once our institution and others are open for in-person visits?

While only 15 percent or less of respondents utilized the museum’s digital offerings (Figure 1), 24 percent said (Figure 2) they would be likely or very likely to use digital offerings in the future. An additional 24 percent indicated they were neutral to digital programming.

With roughly 50% of respondents neutral or likely to consider virtual offerings once NCM re-opened, the Museum felt there was sufficient interest to continue some types of virtual programs, especially given prevailing health and safety concerns. Coupled with the data on educators’ interest in virtual field trips and live educator extension sessions, NCM felt compelled to retain virtual programming as an asset for the museum moving forward.

There are a few important takeaways from the NCM’s experiences with virtual programming:

• NCM’s reach across the country has expanded through free virtual content, contributing to its identity as a national institution. For example, as of September 2021, the Museum has served educators in all 50 states, which is a 90% increase from February 2020.

• Creating new categories of experiences and content has strengthened a culture of innovation amongst staff members, providing the opportunity to think creatively and develop new skillsets.

• Balancing the allocation of resources, especially staff time, between designing and implementing onsite programming and keeping this digital exhibit dynamic with fresh content is highly challenging. Virtual content creation is extremely labor and time intensive, as well as requiring additional investment in equipment and even reallocation of physical space.

• The content available to the public on demand via social media or podcast platforms is free. This has depended on continued success in corporate fundraising.

• By demonstrating its ability to adapt and fulfill the NCM mission in a new environment, the organization was able to tap new funding sources. This extends beyond grants to support content creation; our experience suggests is an opportunity to generate revenue on an ongoing basis from fee-based live virtual trips for primary school classrooms nationwide.

• NCM’s profile has been raised by the significant attention its high-quality virtual programming has received in national media coverage.

• Public engagement plays a key role in sustaining virtual programming, especially in terms of justifying the allocation of labor. A reduction in online consumption would affect the ability to create new content.

Association of Children’s Museums. (2021, March 18) Reflecting on One Year of the Pandemic for Children’s Museums and the Communities They Serve. https://bit.ly/3jhxmJF

Flinner, K., Field, S., Voiklis, J., Thomas, U.G., & ACM Staff (2021). Museums in a Pandemic: Personnel & Rebuilding Teams. ACM Trends 4(12). Knology & Association of Children’s Museums.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 5.2, the second report in the fifth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

For this ACM Trends Report, we invited Scott Burg from Rockman et al to write about his team’s research during the pandemic around parents and caregivers’ preferences for virtual programming by children’s museums. Scott was a speaker at a discussion forum with ACM members focused on virtual programming in October 2021 (See ACM Trends Report 5.1 for details).

Due to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, museums had to make critical decisions about conditions for opening and closing as well as virtual programming based on limited evidence. This shift left children with limited options to engage socially with peers and an increased reliance on parents and caregivers to manage school activities and after-school opportunities. One outcome of the pandemic was an increase in online museum offerings, many of which were targeted at children.

Most museum studies during the pandemic focused on health and safety concerns and returning visits (e.g., mask wearing, social distancing, capacity levels, etc.). This report focuses on results of a study of the potential value of continuing to offer virtual learning activities following the physical reopening of museums. Researchers at Rockman et al (REA) wanted to learn what parents and caregivers felt about children’s museums’ virtual programming, and the types of virtual programs that children’s museums could develop to address families’ needs, interests, and concerns.

In the fall of 2020, REA collaborated with the Children’s Creativity Museum in San Francisco to survey northern California Bay Area children’s museums. The survey collected parent and caregiver feedback on the types of virtual programs they would like to see for their children. Following the first wave of data collection and validation of the instruments, a second wave expanded the research opportunity to other institutions in the Association of Children’s Museums (ACM) network (https://bit.ly/REA-ACM_Blog). In total, 13 different children’s museums across the country distributed the survey to their members and mailing lists.

The REA study focused on understanding the types of virtual programming that parents and caregivers want from children’s museums. Their preferences for types of virtual programs might be influenced by a child’s school or care situations, child age, amount of screen time, cost, and other factors. Each participating museum received real- time access to aggregate study findings as well as their own museum’s individual data through customized digital reports.

Between November 2020 and January 2021, REA gathered more than 1,200 responses from museum patrons. Not all survey respondents answered every question. The bulk of respondents were parents or caregivers of children aged 2-7 (Figure 1). School and care situations varied among participants’ children, spanning those attending school or daycare in person; and those attending virtually either in a hybrid solution (in-person and remote) or being homeschooled or cared for at home (Figure 1).

We found that parents and caregivers’ interest in virtual programs was mixed. About half of all respondents said they had “no interest” or “slight interest” in virtual programs. The other half expressed “moderate” or “high” interest (Figure 2). One overriding concern for participants was the amount of screen time their children were already exposed to. One in five respondents reported that their child spent more than three hours each day on a computer or digital device. Surprisingly, more screen time did not coincide with less interest in virtual programs. These findings suggest that everyone’s threshold for screen fatigue is different.

Our survey showed a correlation between parents and caregivers’ interest in virtual programs, and the type of schooling or care their child was receiving at the time of the survey. Parents and caregivers of children who attended school or daycare in-person were less interested in virtual programs than those whose children were being home-schooled, attended school online or were in a hybrid situation (Figure 3). A child’s age was not related to their parent or caregiver’s interest in virtual programming, suggesting that these issues are based on values rather than a common consensus on developmental concerns.

Despite concerns about screen time, the survey results showed that many parents and caregivers wanted to reconnect with their local children’s museum. They also wanted to replicate museum experiences either at home or in a remote environment.

Parents and caregivers prioritized museum approaches in both virtual and in-person settings that:

Parents and caregivers also indicated an interest in programs that offered the kinds of experiential learning that children’s museums succeed at. These included programs that actively engage participants (e.g., science, art) vs. activities that are more passive (e.g., read alouds, learning study skills). Parent and caregivers were not interested in activities that duplicated virtual school lessons. Nearly three-fifths of respondents said they would consider paying for virtual programming.

Most parents and caregivers preferred virtual programming scheduled on weekends. They indicated a slight preference for weekday virtual programming that allows independent child participation (Figure 4).

The survey did not reflect the many opportunities for children’s museums to educate parents and caregivers on methods to regulate and participate with their child’s virtual learning activities. Research suggests that when parents and caregivers participate and scaffold their children’s activities (asking questions, extending play), this results in higher retained learning (Takeuchi and Stevens, 2011).

Anxiety over prolonged screen time can undermine this type of support. What it means to be an effective ‘digital parent’ can be perceived as contradictory, as parents and caregivers try to minimize the negatives of screen time while benefitting from the affordances of the technology.

Parents and caregivers need support to better understand the content of what their children watch and do on screens, the context of where they watch and do, and the connections they make (or do not make) while watching and doing (Livingstone et al, 2017).

This integrated approach provides more insights into the positive or negative impact of digital media use than a simple measure of time. Parents and caregivers need to be encouraged to think critically about how to support positive uses and minimize negative consequences. This is where children’s museums can play a valuable role.

As the pandemic restrictions are lifted, the needs and expectations of museum audiences will evolve. This survey provided insights into the minds of audiences during the fall and winter of 2020, and but cannot predict what else may change as schools and museums continue to reopen. These data provide some insights that can support analysis and monitoring of how virtual programming is valued in the future.

To put these findings to work, virtual programming offered by children’s museums can respond to these key takeaways:

Are parents and caregivers tired of virtual programs, or has remote learning become a mainstay of education? Is virtual programming enabling visitors to form a new kind of relationship with children’s museums? Can museums use virtual programs to extend their reach to underserved audiences, increase access to diverse communities, or add value to their institutions as trusted sources of information and learning? Where could collaboration between children’s museums or between museums and school districts strengthen both the informal and formal education landscape? What role can researchers and evaluators play in facilitating this discussion?

To answer those questions and build on this study of virtual programming that parents and caregivers want from children’s museums, the researchers hope to expand the number of institutions involved in any future studies to ensure the data are representative and determine if regional variation or museum size influence perceptions. Ideally, future research will recruit a more inclusive sample of community participants including parents and caregivers who may not visit children’s museums regularly or do not have access to virtual programming.

We also hope to encourage the development of research- practice partnerships, which can serve as a critical tool for generating actionable data that children’s museums need to navigate the post-COVID world

Field, S., Fraser, J., Thomas, U.G., Voiklis, J., & ACM Staff (2022). The Expanding Role of Virtual Programming in Children’s Museums. ACM Trends 5(1). Knology & Association of Children’s Museums.

Takeuchi, L., & Stevens, R. (2011). The new coviewing: Designing for learning through joint media engagement. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

Livingstone, S., Lemish, D., Lim, S. S., Bulger, M., Cabello, P., Claro, M., Cabello-Hutt, T., Khalil, J., Kumpulainen, K., Nayar, U. S., Nayar, P., Park, J., Tan, M. M., Prinsloo, J., & Wei, B. (2017). Global Perspectives on Children’s Digital Opportunities: An Emerging Research and Policy Agenda. Pediatrics, 140(Suppl 2), S137–S141.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 5.1, the first report in the fifth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

Volume 4 of the ACM Trends Report series, Museums in a Pandemic, reported findings from regularly conducted surveys by Knology and Association of Children’s Museums (ACM) about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the children’s museum field. Museums closed their doors to the public in March 2020 at the start of the pandemic. More than 70% of ACM member museums were offering virtual programming by June 2020. Last year, museums slowly began reopening for in-person visits and had reached 61% by March 2021. The Spring 2021 ACM COVID impact survey suggested that about two-thirds of museums (n = 43 out of 67) were interested in continuing to offer virtual programming or engaging with communities online even after pandemic restrictions lifted.

In October 2021, Knology and ACM launched the first in an annual series of discussion forums that aim to address emerging questions from the field. Each forum features a panel of external experts that share recent research that might be applicable to the work of children’s museum operations. Presentations are followed by breakout sessions where museum professionals can consider the implications of that research to their practice, and explore their perspectives on the theme more broadly.

Based on the results of the impact survey, this first discussion forum focused on virtual programming. It is important to note that by October 2021, when the discussion forum took place, 91% of ACM members had reopened for in-person activities. We invited leaders and educators from ACM members to share their perspective about virtual programming. A total of 39 leaders and educators from museums across the United States attended the discussion forum. They represented museums that had offered virtual programming during the pandemic, and museums that had not done so. For this conversation, we defined virtual or online programming as programming or exhibits that require at-home or on-the-go screen time. This definition of virtual programming included activity kits if they offered a virtual or online engagement component.

For the October 2021 discussion forum, we invited four experts to present their research. ACM Trends Report 5.1 focuses on the discussions that followed those presentations. During those conversations, the attendees explored the role of virtual programming as part of their institutional missions and culture, as well as their impact assessments of that programming.

The forum discussions included meeting attendee polling, and a Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) exercise with attendees based on their own experiences and institutions. This was followed by a general discussion about the future of virtual programming and possible needs to make that vision a reality.

We conducted live polling during the discussion forum, which helped to benchmark attendees’ opinions to support the discussion. These polls are not considered representative of the entire field. Rather, they represent the attendees’ perspectives.

Most attendees reported that they had either expanded or started virtual programming in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 21). A little over half said that they planned to continue offering virtual programming in future (n = 16). We also asked museums to select the types of virtual programming they have done from a list generated from data gathered from the Spring 2021 COVID impact survey. The most common offering was take-home activity kits that included a live or pre-recorded virtual activity led by museum staff. This was followed by a virtual story time, and other pre-recorded and live videos on social media. Other activities that museums provided included free-play prompts, interactive games, and virtual museum tours.

The SWOT exercise aimed to better understand museums’ experiences with and perceptions of virtual programming. We asked all attendees to participate whether they offered virtual programming or not so that we could get a mix of perspectives.

During the pandemic, many museum educators were tasked with filming virtual education programming for their institutions. As a result, museums invested in infrastructure and systems their staff needed to create and deliver these programs. This allowed museums to build up a library of virtual resources that they can provide to different audiences and share with other institutions. For example, one attendee said that, after participating in the museum’s virtual education programming, some parents of homeschooled children were interested in in-person learning experiences with their children at the museum.

Virtual programming has had other benefits for children’s museums, including increased accessibility. Many respondents said it helped make their programming more accessible to families. Some respondents also shared that the pandemic was an opportunity for their staff to develop new skills in support of virtual programming.

Lastly, many respondents said that working on virtual programming helped them strengthen existing partnerships, particularly with schools and educators. For example, one museum developed a website that showcases content from their exhibits, which they shared with local educators.

The limits of virtual programming meant the museums had to think creatively about how to engage with families in their communities. Feedback from museum staff and leadership indicated that some felt that switching to virtual programming took away many of the elements of play they curated for their in-person visitors. Some respondents indicated they struggled with creating programming because virtual learning pedagogy was unknown or unfamiliar to them. Museums also had to consider the trade-offs and benefits to children’s learning between pre-recorded and live virtual sessions.

Museum staff described challenges with developing the skills needed to provide virtual programming. Some staff described difficulties with forming connections online audiences. Not all museum educators were comfortable with presenting content in an online format. Because of these experiences, some museum staff wanted resources about best practices for providing programming in virtual environments.

Museums either released or furloughed on average between 40 – 55% of their staff (ACM Trends Report 4.12). We heard from several participants that as a result they lacked the time and resources to produce high quality virtual programming. Some museums chose not to produce any virtual programming. Also, a few museums charged a fee, which may have prevented some families from accessing their programming.

Several attendees said they needed resources to help them continue providing virtual programming. One suggestion was to develop a platform where museums can exchange curriculum, media assets, and other resources related to providing effective virtual programming. Some museums have already taken steps to begin sharing resources. For example, one attendee said their institution was working with a consortium of other museums in California to collaboratively develop five activity kits that include video components they would share equally as a resource. By pooling their resources and working collaboratively on the content, these museums created higher quality kits and videos for their communities, while limiting costs and burdens on museum resources.

Some museums described opportunities for continuing virtual programming in partnership with local schools. These partnerships help extend the museum experience beyond in-person interactions to include learning in other contexts. One museum, which created a website with lesson plans for educators during the pandemic, now works with the local teachers. They are now developing targeted field trips that have a classroom component and an in-person or virtual experience.

The primary threats to continuing virtual programming in children’s museums are time, energy, and return on investment given the variability in attendance. Creating virtual programming can be a strain on both staff capacity and museum resources. One museum leader said they would need to staff a department dedicated to virtual programming to continue providing this type of service. Another museum leader said their pandemic virtual programming was necessary, but likely beyond their means when the museum returned to full operations due to staffing and budget constraints.

Many attendees felt that the return on investment was not sufficient for staff to continue virtual programming at their institutions. Concerns included the lower revenue from virtual programming when compared to live in- person programming. A few mentioned they were redirecting resources from virtual programming back toward reopening activities. One attendee said their museum’s partnership with Amazon Affiliates had helped to reduce their spending on virtual programming and enabled them to provide free or low-cost activity kits to families. But most leaders said that continuing to provide this kind of programming may not be sustainable without additional sources of funding.

Another critical concern raised in this session was Zoom Fatigue, the sense that interacting on screens had become overwhelming for working families and school age children. Attendees observed that many parents and caregivers who were responsible for supporting their families and helping their children with formal online learning seemed less inclined to engage in additional virtual learning with museums.

During the pandemic, museums reimagined their operations and service, and this has affected the staff. As COVID-19 restrictions are lifted, many museums have re- opened their doors to in-person visits. As of March 2022, 92% of ACM members globally are open the public (up from 91% when the discussion forum took place in October 2021). This has implications for the future of virtual programming in children’s museums. Museum staff shared their perspectives based on their experiences during the pandemic, and their thoughts on continuing to provide online content in future.

Museum staff said that virtual programming offered during the pandemic was most successful when it was done in partnership with local schools and educators. They also said that partnership was the most sustainable way to continue offering virtual programming in future. However, they noted that there was a lot less demand for virtual programming now that children’s museums and schools have re-opened for in-person activities.

Most attendees reported that they were re-assigning staff and resources from virtual programming back to their traditional in-person activities. Several mentioned the limited staff time available to keep offering virtual programming, even though they felt it was valuable extension of services. Some children’s museum staff reported developing a backlog of virtual content they could roll out slowly over time, but most had no plans to develop new virtual content once full operations resume.

Overall, attendees were reluctant to continue with virtual programming without financial sponsorship. They reported that the funding for virtual programming during COVID-19 restrictions came from grants, but even that was relatively minimal. They suggested that hiring additional staff who would be responsible for fundraising, planning and executing virtual programming might allow these programs to continue.

There are a few important takeaways from the responses to the polling questions and the outcomes of the SWOT exercise:

and

Flinner, K., Field, S., Voiklis, J., Thomas, U.G., & ACM Staff (2021). Museums in a Pandemic: Personnel & Rebuilding Teams. ACM Trends 4(12). Knology & Association of Children’s Museums.

Association of Children’s Museums. (2021, March 18) Reflecting on One Year of the Pandemic for Children’s Museums and the Communities They Serve. https://bit.ly/3jhxmJF

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 4.14, the final report in the fourth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

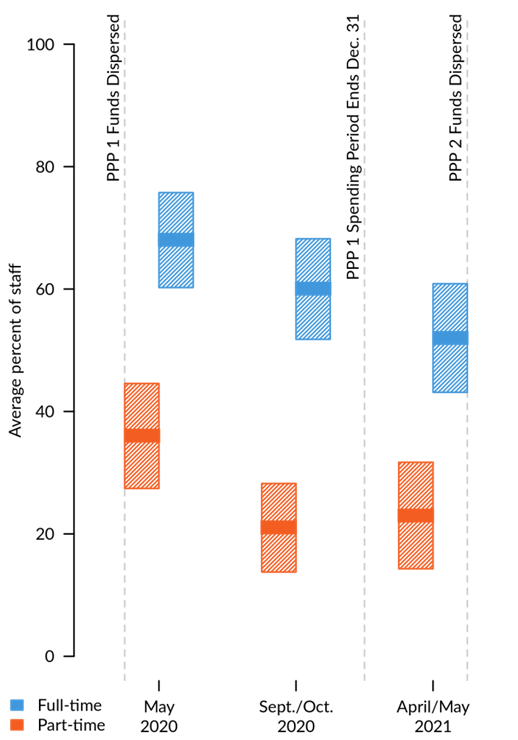

This is the final report in the Museums in a Pandemic volume of the ACM Trends Report series. Since March 2020, the ACM Trends Report team has tracked the impacts of the pandemic on children’s museums through surveys, conversations, and other data collected by ACM. This ACM Trends Report presents data from museums that responded to our Spring 2021 survey.

Throughout the pandemic, we collected data on children’s museum operations and what was vital to their survival. We benchmarked this information against 2018 fiscal year 990 data. We used these data because 2018 represents the last pre-pandemic fiscal year for all of the organizations in our sample set. This comparison helped us understand the pandemic’s impact on museum operations.

As the pandemic continued into 2021, children’s museums were balancing re- opening to the public with the continued need to focus on securing necessary funding to keep operations going. We documented ACM members’ fundraising efforts in the early stages of the pandemic (ACM Trends #4.2 and #4.7).

By Spring 2021 many museums were welcoming visitors back into their spaces, with new safety protocols in place and varying capacity restrictions. Museums rely on these patrons to sustain operations. When we reviewed 2018 990 financial data from 218 museums in the ACM member network, our analysis showed that the median institution (regardless of size) relies on program services income (this includes income derived from admissions, events, and other general operational activities) for roughly 45% of its total income. Attendance directly impacts how museums balance income and expenses. By the time of this survey in Spring 2021, the numbers of visitors to the museums had not returned to pre-pandemic levels. This dip continues to impact children’s museums’ income.

To track how the field’s attendance had changed throughout the pandemic, we captured monthly total attendance numbers from March 2019 to March 2021. Sixty-two museums responded to this portion of our Spring 2021 survey. From this data set, we know that the average museum was open to in-person visitors for 34% of the total days during the pandemic’s first year than the year prior. Additionally, based on survey data from 52 museums, we know that in March 2021 attendance for the average museum remained at 26% of pre-pandemic attendance levels.

Knowing that museums rely on their patrons for 45% of their total income from program and services revenue, we asked for up-to-date data, as of March 2021, on fundraising during the pandemic. Specifically, we looked at governmental and non-governmental funding sources. As we reported in ACM Trends Report 4.7, the median value of funding from governmental sources in September 2020 was $205,000 (N = 96). Of the 96 museums responding, 77 had approached private funders (ACM Trends #4.13) with an average return of $50,000.

A second round of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) funding was awarded in early 2021, in time for award announcements before the Spring survey. At this time, most museums responding to the survey (n = 80) reported moderate success in obtaining government funds during and related to the COVID-19 pandemic, exhibiting an 80% success rate with a median value of almost $400,000. Appeals for private funding were even more successful (98% success rate) but yielded smaller amounts, with a median value of just over $100,000.

Two new streams of funding were available to museums to apply for through the American Rescue Plan Act and the CARES Act. In March 2021, nearly one-third of museums (n = 27) indicated that they had applied or intended to apply for a Small Business Administration Shuttered Venue Operators Grants (SVO). At the time of the survey, SVO had not yet been distributed.

Additionally, just over one-third of museums (n = 32) indicated that they had received Employee Retention Tax Credit (ERTC) funds, with the median museum receiving $290,328. We have not collected further data on either the ERTC or SVO at this point.

Fundraising success is about more than securing grants. Museums are constantly looking for new funding sources and streams and setting goals to meet operating budgets. This remained true during the pandemic. Reviewing 218 museum’s 990 information, we found that the median museum relied on donations for almost half of their total income. In the Spring 2021 survey, we asked children’s museums whether their fundraising efforts were more successful, just as successful, or less successful during the first pandemic year (March 2020 – March 2021) compared to the previous year. Three-fourths of museums indicated that fundraising was just as or more successful during the first pandemic year (n = 79).

In Spring 2021, children’s museums were generally confident that they could meet their financial obligations one year on in Spring 2022. Eighty museums responded to the question “How confident do you feel that your museum will be able to maintain its financial obligations to maintain operations a year from now?” on a scale from Not at all confident to Very confident. Slider responses were recorded as numerals between 0.00 and 1.00, accordingly.

Seventy-three museums responded with a degree of confidence equal to or higher than 0.5, indicating that museums had found a way to compensate for the financial hit caused by drastically lower attendance numbers.

Government funding proved vital for many museums. Overall, their fundraising success during the pandemic seems to have stimulated children’s museums’ confidence.

Figure 1 above is a Box and Whisker Plot displaying the responding museums’ confidence (n = 80). We will explain each element of the Box and Whisker Plot and what it shows about our data. Box and Whisker Plots are useful for displaying the range of values in a dataset, including the median value and quartiles of the data’s spread. Each quartile includes 25% of responding museums. Here, the orange box shows us the second quartile, the third quartile, and the median values of our data. The median is represented by the vertical line down the middle of the box. The left “side” of the box displays the second quartile, and the right “side” of the box displays the third quartile. The purple dot in the second quartile is the mean, or average value, of our data set. The whiskers, or the horizontal lines, on either side of the box show us the first and fourth quartiles. The five blue dots ranging between 0.10 and 0.45 are outliers.

So, what does all this mean in the context of museums’ confidence in meeting their financial obligations? By looking at the median, we can tell that the middle value of our data set represents a museum that is quite confident that it will meet its financial obligations in Spring 2022.

On a scale where a rating of Not at all confident yields a value of 0.00 and a rating of Very confident yields a value of 1.00, a median value of 0.85 reflects fairly high confidence. Meanwhile, the orange box tells us that half of the museums in the dataset, or 40 out of 80 museums, are moderately to very confident that they will meet their financial obligations in Spring 2022.

The short right whisker tells us that 20 museums are very confident in their ability to meet their financial obligations. Of the remaining 20 museums, five (represented by the blue dots) are less than confident about meeting their financial obligations. The box’s long left whisker shows that the first quartile of museums is somewhat confident in meeting their financial obligations. The takeaway is this: 75% of the museums in this data set are moderately to very confident that they can meet their financial obligations in Spring 2022. In the following sections, we explore the reasons for their optimism.

Every museum has a unique rationale for any confidence it has about its late- and post-pandemic future. However, we identified six general categories that illustrate why museums are right to feel confident. Thirty museums referenced a diversified funding stream, including federal and local government funding as well as private funding, as a reason for confidence. Twenty-seven museums have been encouraged by attendance during their re-opening phases and have received more visitors than anticipated. Twenty-three museums indicated that a reduction in operational spending as part of a long-term planning strategy, along with current cash reserves, meant they could be confident about meeting future operational needs.

Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, reducing operation spending also included a reduction in staff. We detail the impacts of staffing over the course of the Pandemic in ACM Trends Report #4.12.

Additionally, seven museums in our data set either belong to a larger museum/university structure or are completely funded by local government and have moved to more sustainable budgets to ensure future operations. Finally, one museum mentioned that rent reduction has been helpful, and four museums moved into new spaces with higher capacity and lower operating costs.

In the past year, museums have reimagined their operations and service to their communities, and this has affected their staff. During an ACM Leadership call in Fall 2021, about 6-months after the Spring 2021 survey, ACM and Knology followed up with roughly 20 ACM member museum leaders to hear if they were still confident in meeting their operations’ budgets in 2022.

With attendance not yet back up to pre- pandemic levels, museum leaders’ confidence in meeting financial obligations in 2022 was high yet speculative. On a scale of 1 (least confident) to 5 (most confident), museum staff on the call indicated confidence between 3 and 5, with specific caveats and new concerns. Key concerns centered around the continued need for federal and state governmental funding to fill in the gaps of lowered earned revenue. Specifically, the Shuttered Venue Operating Grants and PPP loans were still covering many 2021 costs and were projected to continue to support museum operations into 2022. A second round of SVOG and funds from the Employee Retention Tax Credit were noted as potential future governmental funds that these museums were banking on. A museum CFO noted that, “Once the federal funding runs out, our confidence drops off tremendously not knowing which direction covid stats are going to go. Just when we thought it was getting back to ‘normal’ the Delta variant picked up. What’s next?” This was met with widespread agreement from others in attendance.

Museums staff noted that donations from individuals and foundations were starting to taper off, with many noting that perceived “sympathy giving” at the height of the pandemic in 2020 was not as common in Fall 2021. Many did not expect their fundraising to be as successful in 2022 compared to their early pandemic success.

We will continue to monitor the state of the children’s museum field into 2022 to understand how these concerns impact their missions and operations.

The data used in this report came from an online survey that ACM sent to US-based children’s museums. Overall, 91 museums responded to at least part of the survey. All participating museums were based in the US. Additional data was collected through an ACM Leadership call discussion forum where data was presented back to museum leaders for their response.

Flinner, K., Voiklis, J., Field, S., Attaway, E., Gupta, R., & Fraser, J. (2020). Museums in a Pandemic: Financial Impacts. ACM Trends 4(2).

Flinner, K., Voiklis, J., Field, S., Thomas, U.G, Attaway, E., & Gupta, R. (2021). Museums in a Pandemic: Diversifying Funding Streams. ACM Trends 4(7).

Flinner, K., Field, S., Voiklis, J., Thomas, U.G., & ACM Staff (2021). Museums in a Pandemic: Personnel & Rebuilding Teams. ACM Trends 4(12).

Fraser, J., Field, S., Voiklis, J., Attaway, E., & Thomas, U. G. (2021). Museums in a Pandemic: Patterns in Fundraising. ACM Trends 4(13).

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 4.13, the thirteenth report in the fourth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

Since May 2020, the ACM Trends Report team has tracked the impacts of the pandemic on children’s museums and the field’s innovations through survey studies and other data collected by ACM.

This ACM Trends Report presents data from 28 museums that shared information on their donors and funds received by Spring 2021. This includes 147 corporate donations and 119 private foundation donations made to children’s museums. Corporate donations were stratified into categories by type of donor. We also collected data on whether the funds were provided as restricted or unrestricted gifts. To understand the pandemic’s impact on donations, this information was benchmarked against 2018 fiscal year 990 data. Comprising the most complete data to date, the 2018 fiscal year represents the pre-pandemic fiscal year for all organizations.

Three small museums, 10 medium museums, and 11 large museums provided information on corporate donations received during the pandemic. We also learned about a few extraordinary donations that represented historical commitments to large children’s museums, which should not be considered typical of the day-to-day fundraising expectations.

This early assessment of donor type, scale of donation, and comparisons helped us learn how to support comparison between museums irrespective of scale.

We normalized the data by comparing the percentage of total income from corporate and private funding received during the 2018 fiscal year to the percentage of total income from corporate and private funding received during the pandemic. This way, we were able to develop clear benchmarking that can be used by all children’s museums to consider their relative prospecting success and opportunities in their markets. This report focuses on understanding how to benchmark and set reasonable expectations for donation size as our field emerges from the pandemic.

An assessment of the 2018 nonprofit tax filings for all ACM member museums showed that an average children’s museum receives 47% of total income from donations and gifts. While some museums rely more heavily on donations than others, museum size did not impact total percentage of income from donations.

Museum development teams build an understanding of their local supporters and focus on relationships that can last over time. As a result, many of these gifts may be a function of annual giving unique to each community. This report focuses on whether there are patterns to giving that can help museum leadership set expectations. The context for this study was the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 civil rights protests, which caused donors to reconsider their funding priorities.

We explored a snapshot of fundraising results from the 2020 pandemic year to assess how these varied from pre- pandemic times. We also looked at donors by industry to aid in benchmarking anticipated gifts from any representative of the sector, and whether being part of a local, regional, or national brand impacted the size of gifts.

Twenty-four museum respondents reported corporate donations received during the pandemic. These donations ranged from $100 to $100,000. Most donations were below $5,000 (Figure 1). Around 2/3 of donations (n = 98) were gifted as unrestricted funds, 40 were completely restricted, and six were partially restricted. Larger donations were more likely to have restrictions attached.

Let’s walk through how to read this figure. Each black circle represents an individual donation from a corporation or corporate foundation. The purple line shows the mid-point (median) of the distribution of donations. The orange line represents the average (mean) corporate donation in this dataset. The mean is calculated by summing up all the numbers in a dataset and then dividing by the number of values in the dataset. This is different from the median which refers to the middle number when a set of numbers is placed in order smallest to largest. Three outlier donations (two of $70,000 and one of $100,000) are not shown in Figure 1 but are included in calculations.

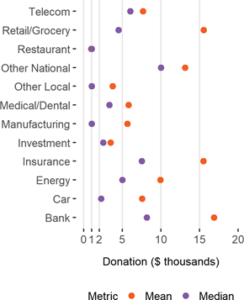

Because firm size and industry impact corporate giving (Amato & Amato, 2007), we categorized the set of corporate donations by industry and discovered that different-sized corporate donors gave varying gift amounts. To understand how to benchmark these gifts for comparison purposes, we suggest that is more relevant to consider the “median” donation rather than the “mean,” as one large donation to one museum can skew the results of the average.

Let’s walk through how to read the next pair of figures. Here, the circles represent donations from corporate donors and corporate foundations to children’s museums. The purple circles show the median donation for each industry while the orange circles show the mean donation for each industry.

Figure 2. Comparing the mean and median donation to children’s museums from corporate donors and corporate foundations.

Our analysis of this small dataset suggests a few things, but we would need additional data to more fully understand the funding patterns of corporate donors and make recommendations as to how children’s museums might approach them. These data suggest that if a museum were to approach an energy company for funding, they might be more likely to succeed if they explain that many children’s museums are supported by energy companies at the $5,000 level, but a few energy companies make large gifts that average $10,000.

While this approach may seem to reduce the potential gift, it helps to establish two norms or social expectations for the industry that could benefit children’s museums in the long term. Industrial and organizational research has shown that corporate donations are likely to level to match the norms for their industry, but are modified by regional norms across industries (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2016). Presenting funding request in this way may increase willingness of corporate donors to consider small gifts that were not on their priority list because they wish to represent their corporate citizenship as consistent with industry standards.

We also categorized corporate donations by the service territory. National brands were more likely to donate in the $10,000 range, regional brand gifts were at the $5,000 level, while local businesses hover around $1,000 (Figure 3). As noted, these are early findings, and we will continue to gather additional data in future surveys.