| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 6.1, the first report in the sixth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

Members are the lifeblood of many children’s museums. They are loyal patrons who trust museums to provide playful learning opportunities for their children, often complementing trips to the zoo or aquarium. But when children “age out,” families may turn to other cultural institutions and start to reconsider the value of their membership. Understanding value seekers’ calculations can help children’s museums cultivate trust through transparency.

In this Trends report, we look at what membership pricing and attendance data can tell us about children’s museums. We focus on what museums might want to think about when attempting to stabilize their membership base, and on how to forge trusting relationships with prospective members.

National data related to membership pricing has been of particular interest to the ACM leadership community in recent years, especially as it relates to post-pandemic operations. Prompted by a specific request from an ACM member, this report contributes to these ongoing discussions. We used data from the Spring 2022 targeted ACM member survey and collected additional information from member museum websites. We developed a dataset from 90 children’s museums to see if there were differences in membership costs between small, medium, and large museums. We also compared admission prices across these categories and calculated a “pay less” point—that is, the number of times a family of four would need to visit in order to make the

purchase of an annual membership a cost-saving act.

Our analysis yielded two main findings. First, even though admission prices and membership costs are highest for large museums, the number of single visits needed by a family of four to “pay less” is lower for these museums than it is for their small and medium-sized counterparts. Second, we confirmed that admission prices and membership costs tend to rise in parallel, which means that even though base admission prices may be determined based on local cost of living concerns, ACM members can still compare their rates to other children’s museums, Taken together, these findings can help children’s museums determine how to align pricing decisions with the needs and interests of value-seeking visitors—that is, those who purchase memberships based on a calculation of savings.

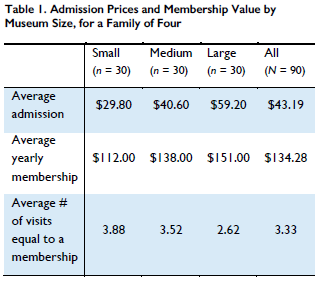

In Spring 2022, the ACM Trends Team circulated a survey to ACM member institutions requesting data on attendance, admission prices, membership costs, and other operations. After supplementing this data with information gleaned from member websites in August 2022, we assembled a dataset of 90 museums (30 of each size). We summarize the data in Table 1 below.

Table 1 compares admission and membership prices for a family of four at small, medium, and large museums. Admission prices are based on the general admission price for adults and children. When prices for adults and children were different, a family of four was calculated with two adults and two children.

We calculated these figures for a two-adult, two-child family on account of current US Census data (which shows that the average US family contains 3.13 people), and because this aligns with demographic research showing that a plurality of mothers in the US today report having two children (Pew Research Center, 2015).

The bottom row in Table 1 presents the average number of times a family of four would need to pay admission before achieving cost-savings through a membership purchase. The fourth column illustrates the mean cost across all size categories—which is an appropriate way to calculate averages in a dataset like this one, as it contains few outliers.

Clearly, the larger the museum, the higher the membership and admission costs for a family of four. Nevertheless, the number of visits needed for a valueseeker to “pay less” for multiple visits through a membership is lower (2.62) for large museums than for their small (3.88) and medium-sized (3.52) counterparts.

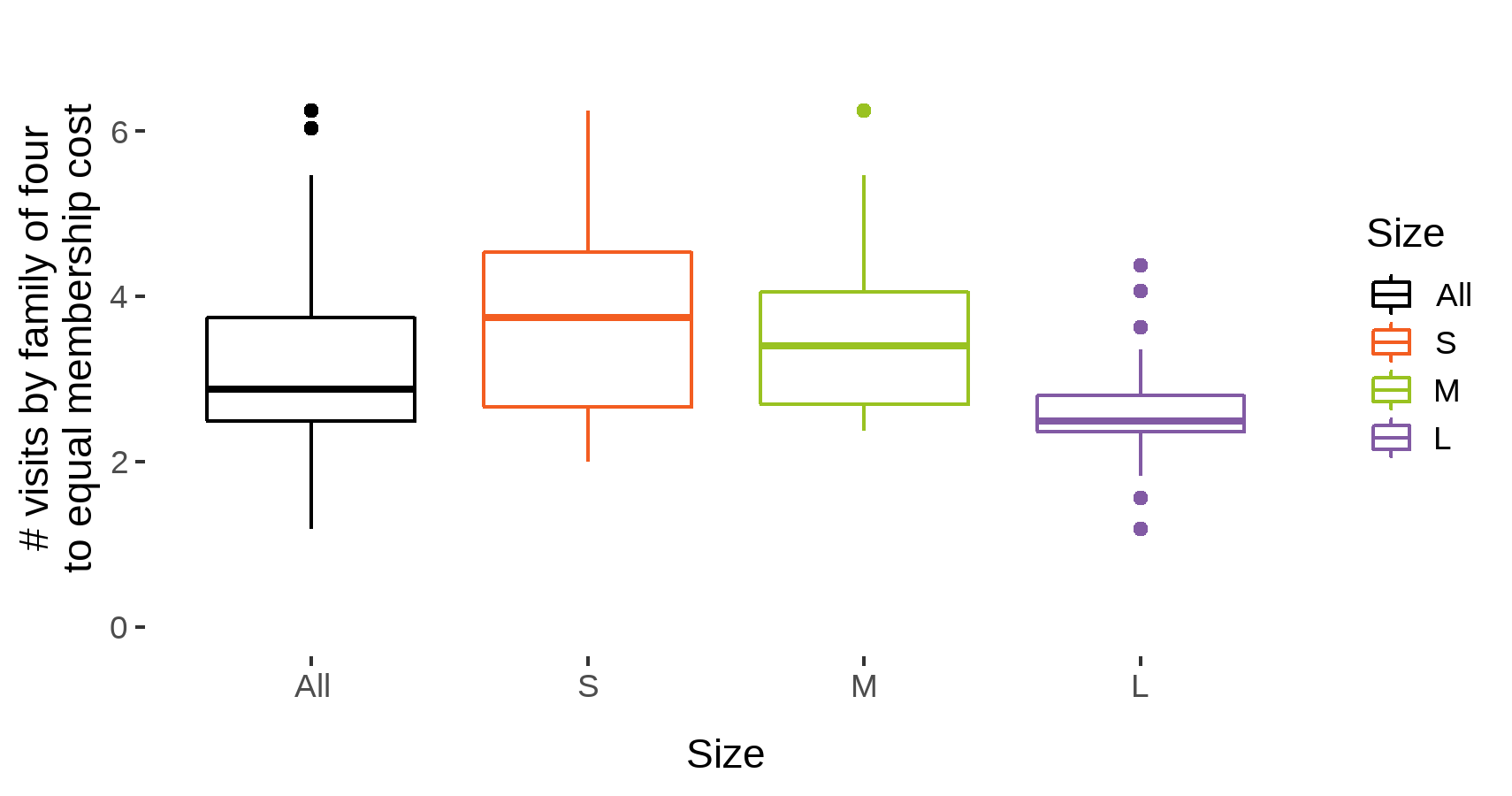

Figure 1 presents data from the bottom row of Table 1 as a “box and whiskers” plot. To create this, we “normalized” pricing data to show membership costs (for a family of four) as a multiple of admission costs for each children’s museum. The “box” part of the plot illustrates the middle half of the data (in other words, where 15 of the 30 museums in each size category sit), while the “whiskers” indicate those museums where prices are higher or lower than their peers.

When a museum stands alone compared to others, the box and whiskers plot expresses this with dots, considered outliers. When multiple museums lie in the same range, this is indicated by a line placed above the box. The line in the middle of the box illustrates the median, or the exact middle of all of the data in that category. We can see from those lines that medium-sized and small museums tend to be near one another. To see how many visits a family of four would need to make before generating savings through the purchase of a membership, look at the Y-axis, which plots the ratio of membership costs to visit price. This data can be used as a foundation for making decisions about membership pricing, especially in connection with data on premiums.

We also collected data on additional benefits provided with museum memberships—for example, discounts for rentals or birthday parties (n = 60), member-only events (n = 53), and reciprocal admission to other ACM (n = 24) or ASTC (n = 13) member institutions. Most museums offer these in some form; 8 out of 10 small museums, 9 out of 10 medium-sized museums, and all large museums indicated additional membership benefits. The total number of additional benefits did not appear to be related to a higher value of memberships.

One benefit, however, did have a significant effect on “trips to match cost.” Offering a discount on space rentals, after accounting for museum size, was related to higher membership costs. Though some have suggested that early access or discounts on summer camps are perceived as an incentive for families who can afford summer camp experiences, our analysis did not provide any evidence that the benefit is related to higher or lower membership prices.

We also looked at a subset of the data from fifty-one museums (1 small, 15 medium-sized, 20 large, and 3 yet to be classified) who responded to the Spring 2022 ACM member survey and provided information on annual attendance and member attendance from FY2016 to FY2021. Looking at the data, we can determine historical trends in museum attendance, and also calculate the proportion of overall attendance consisting of museum members.

Prior to the pandemic, in FY2016 through FY2019, the median number of memberships purchased per year for these museums was between 2200 and 3000. In FY2020 and FY2021, this value dropped to 968 & 1188 memberships purchased, respectively. Along with this decline, the proportion of overall visitors who were

museum members decreased roughly 6% in 2021 for these museums. While these museums are just a portion of the overall ACM field, the decline likely reflects the impact of the pandemic across the sector.

People purchase museum memberships for different reasons. These purchases provide a reason for frequent visits—which not only benefits children but can also help museum leaders advocate for children’s access to the healthy spaces of learning and discovery children’s museums provide. For some, a membership is a valueseeking purchase, one made through a consideration of future costs, benefits, and savings. Value-seekers become members because they want museum-going to be a regular part of their children’s lives. These pricing data tell us that museums anticipate four visits a year by their value-seeking members, setting prices that justify at least four or more visits in a membership year.

For others, purchasing a membership may not be driven by monetary concerns. They may simply want to invest in an institution that is doing good work, or to support a local institution that is good for children. Some individuals may purchase memberships to build social capital, because they want to support an organization whose values they identify with, and because they want their membership to reflect something about who they are. They may also become members because they want to encourage their grandchildren, nephews, nieces, or other relatives to visit them, or because they want to provide gifts to families with children. These “affinity members” may also care less about free admission than about membership perks, premiums, or about symbolic value—for example, discounts on birthdays or group tours, reciprocal admission at other ACM member museums or other cultural institutions, access to priority registration, exclusive programs, or behind-the-scenes content.

In other words, value is a complex, multidimensional thing. When thinking about those who see the primary value of a museum as its price, children’s museum leaders can also consider how decisions related to pricing might impact the perceived trustworthiness of their institutions. As ACM Trends #5.3 discussed, in order to cultivate public trust, museums need to demonstrate competence, reliability, sincerity, integrity, and benevolence. During the height of the pandemic, many museums demonstrated benevolence through refunds or by pro-rating existing memberships. At present, some museums are considering increased fees to recoup pandemic-related monetary losses. Doing so may risk the trust built through the pandemic, especially as cost-of-living increases may make more members value-seekers.

Data for this report was collected through: (1) an online survey distributed by ACM in April 2022; (2) a review of ACM member institutions’ websites. This dataset contains information from 90 current ACM member museums.

Our analysis used the size categories developed in ACM Trends Reports #1.1 and #1.7. We use these categories because institutional size predicts a range of outcomes for children’s museums. We note that museums offer many types of reduced priced tickets or free admission, and some unique premiums that were not used in this analysis.

Voiklis, J. (2022). Key Concepts: Trust. ACM Trends 5(3). Livingston, G. (2015). “Childlessness Falls, Family Size Grows Among Highly Education Women.” Pew Research Center.

US Census Bureau (2021). America’s Families and Living Arrangements. Retrieved from: [https://www.statista.com/statistics/183657/average-sizeof-

a-family-in-the-us/]

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 5.4, the fourth report in the fifth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

For this ACM Trends Report, we invited staff from National Children’s Museum in Washington, DC, to write about their experiences with virtual programming during COVID-19. Staff from the museum participated in the October 2021 discussion forum focused on virtual programming (See ACM Trends Report 5.1 for details).

After seventeen years without a permanent home in Washington, DC, National Children’s Museum (NCM) reopened as a science, technology, engineering, arts, and math (STEAM) focused institution on February 24, 2020. Eighteen days later, the Museum temporarily closed as a precaution against COVID-19, and committed to providing families and educators with free, meaningful experiences at home. When the institution reopened, NCM continued to offer virtual programming for children under twelve and their families, garnering more than three million impressions to date.

While preparing to reopen, NCM conducted a survey to better understand the community’s engagement with the museum, including its virtual offerings. Fifty percent of respondents indicated they would be likely or very likely to engage with virtual offerings once NCM opened. Although the virtual offerings were initially developed in response to a need created by the pandemic, they are now part of the museum’s ongoing programmatic strategy.

This ACM Trends Report describes the survey items related to virtual programs and the current “evergreen” programming that will be retained based on these data.

When NCM reopened to in-person visits in September 2021, it began complementing its on-site programming with the on-demand resources developed during the pandemic. As NCM looks to the future, staff are committed to maintaining, and in some cases, expanding the museum’s virtual offerings. All of the virtual experiences created during NCM’s pandemic closure are fully aligned with its mission and continue to be essential to its ability to promote its mission to audiences locally and abroad.

Between March and May 2020, NCM produced free STEAM videos that premiered seven days a week on its social platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter). Funded by Booz Allen Hamilton, the series called “STEAMwork” featured experiments, projects, design + build challenges, story times, and demonstrations.

These videos and accompanying resources were made available free-of-charge on NCM’s website and continue to be featured as “STEAM At Home” opportunities in the museum’s newsletter. Staff also send the videos to educators as a post field trip resource for continued learning.

One NCM exhibit that was successfully adapted is its Climate Action Headquarters. In the pre-pandemic era visitors had participated in monthly missions and climate challenges. The virtual format introduced during the pandemic allowed visitors to determine their own climate action hero persona by answering a playful online quiz. This virtual version is available as part of NCM’s STEAMwork series. At this writing, NCM staff anticipate producing additional STEAMwork videos and related resources with ties to curriculum standards to promote classroom use.

With funding from GEICO and The Akamai Foundation, NCM launched the STEAM Daydream with National Children’s Museum podcast in June 2020 to provide tailored content to young audiences.

Staff engaged 3rd– to 5th-graders as interviewers. The first season had 18 episodes on critical, timely issues. Each episode allowed young learners to hear from STEAM experts, ask questions, and understand the world around them. Topics included:

• What children want to know about the COVID-19 vaccine with Dr. Roberta DeBiasi, the Chief of Infectious Diseases at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, DC,

• The wonder of animation with Dave Cunningham, Supervising Director of Nickelodeon’s SpongeBob SquarePants.

The Museum’s podcast, featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Vox, was streamed 5,000+ times, with 15% international listenership for the first season. In 2022, NCM began production for the second season of the podcast for debut in the fall, followed by an assessment to determine the feasibility of a third season.

NCM also developed two 20-minute virtual field trip videos based on in-person offerings. These virtual trips were offered to educators and families free of charge. Both virtual field trips are aligned with Common Core State Standards and Next Generation Science Standards. So far, the videos have been requested by thousands of educators across all 50 states.

The first video, “Head in the Clouds,” prompts budding young scientists to observe and identify different types of clouds. When this video was released in May 2020, the museum received 475 initial requests for it from educators and caregivers. Of those 475 requests, 285 were from educators, who almost universally expressed interest in having their class participate in virtual extension sessions related to the video.

This demand enabled the museum to secure funding from a media company to develop a second video, “Climate Action Heroes.” This video explored the difference between weather and climate and introduces learners to seven real-life climate action heroes from across the country.

To extend learning beyond the videos, NCM has offered classroom teachers the opportunity to sign up for “live virtual extension sessions’’ with museum educators. These hour-long sessions, held over platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams, help youth in formal classroom settings delve deeper into complementary content, participate in virtual activities, and ask museum educators questions.

Grant-funding through the end of 2021 offset the fee-based model for local Title 1 schools to book the sessions at no cost. Between May 2020 and June 2021, NCM fielded requests from 1,401 educators interested in live classroom sessions. Overall, NCM received 2,382 overall requests for access to the “Head in the Clouds” and “Climate Action Heroes” videos.

At this writing, staff plan to focus on content designed specifically for 3rd to 5th grade, which make up the majority of onsite field trips at the museum. Staff believe that this audience will be best served through live virtual field trips led by museum educators.

Based on the scale of these programs, NCM added a dedicated second full time educator to focus on teaching live extension sessions. The internal analysis also confirmed the museum will require dedicated space for a virtual field trip studio to allow educators the privacy and technical setup to teach effectively.

Lastly, the team recognized that programming developed during COVID tended to be longer than newer audiences anticipate. They concluded that offering shorter, fee-based classes, as well as promoting live virtual field trips to a national audience may be an effective use of resources.

NCM shared a re-opening survey through their newsletter, which had nearly 10,000 subscribers at the time of distribution. The 316 returned surveys translate to a (roughly) 3% response rate.

The survey asked two questions on virtual programming:

• During National Children’s Museum’s temporary in-person closure, did you use any of the museum’s digital offerings? If so, please check all that apply.

• How likely are you to continue to use–or begin to use–the museum’s digital offerings once our institution and others are open for in-person visits?

While only 15 percent or less of respondents utilized the museum’s digital offerings (Figure 1), 24 percent said (Figure 2) they would be likely or very likely to use digital offerings in the future. An additional 24 percent indicated they were neutral to digital programming.

With roughly 50% of respondents neutral or likely to consider virtual offerings once NCM re-opened, the Museum felt there was sufficient interest to continue some types of virtual programs, especially given prevailing health and safety concerns. Coupled with the data on educators’ interest in virtual field trips and live educator extension sessions, NCM felt compelled to retain virtual programming as an asset for the museum moving forward.

There are a few important takeaways from the NCM’s experiences with virtual programming:

• NCM’s reach across the country has expanded through free virtual content, contributing to its identity as a national institution. For example, as of September 2021, the Museum has served educators in all 50 states, which is a 90% increase from February 2020.

• Creating new categories of experiences and content has strengthened a culture of innovation amongst staff members, providing the opportunity to think creatively and develop new skillsets.

• Balancing the allocation of resources, especially staff time, between designing and implementing onsite programming and keeping this digital exhibit dynamic with fresh content is highly challenging. Virtual content creation is extremely labor and time intensive, as well as requiring additional investment in equipment and even reallocation of physical space.

• The content available to the public on demand via social media or podcast platforms is free. This has depended on continued success in corporate fundraising.

• By demonstrating its ability to adapt and fulfill the NCM mission in a new environment, the organization was able to tap new funding sources. This extends beyond grants to support content creation; our experience suggests is an opportunity to generate revenue on an ongoing basis from fee-based live virtual trips for primary school classrooms nationwide.

• NCM’s profile has been raised by the significant attention its high-quality virtual programming has received in national media coverage.

• Public engagement plays a key role in sustaining virtual programming, especially in terms of justifying the allocation of labor. A reduction in online consumption would affect the ability to create new content.

Association of Children’s Museums. (2021, March 18) Reflecting on One Year of the Pandemic for Children’s Museums and the Communities They Serve. https://bit.ly/3jhxmJF

Flinner, K., Field, S., Voiklis, J., Thomas, U.G., & ACM Staff (2021). Museums in a Pandemic: Personnel & Rebuilding Teams. ACM Trends 4(12). Knology & Association of Children’s Museums.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 5.3, the third report in the fifth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

This ACM Trends Report delves into the topic of trust, which is particularly important as museums reach out to new audiences with activities such as virtual programming. Knology researcher John Voiklis shares what research suggests about the nature of trust and its impact on the relationship between a museum and its audience(s).

Virtual programming became an unplanned necessity when children’s museums had to close their doors to the public during the pandemic. Nevertheless, it began to fulfill a long-sought goal of children’s museums: reaching previously unreachable audiences.

This benefit was cited by participants in the surveys that were reported in Volume 4 of the ACM Trends Report series, and by participants in the first annual discussion forum hosted by Knology and Association of Children’s Museums (see ACM Trends Report 5.1). During the forum, participants talked about using virtual programs to cultivate trusting relationships with new audiences.

This ACM Trends Report differentiates between two types of trust identified by social scientists: identity-based trust and experience-based trust (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, 1998). It reviews evidence from a large-scale study Knology conducted with institutions that share audiences with children’s museums and play a similar role in the social, emotional, and cognitive development of children: zoos and aquariums. The study shows the particular importance of experience-based trust in building trusting relationships with a broad audience. Lastly, the report explores how children’s museums might apply what Knology learned about experience-based trust to outreach efforts such as virtual programming, focusing on two facets: Reliability and Benevolence.

Trust ranks as a major concern in the museum field (Museums and Trust 2021). Moreover, it plays a foundational role in all human relations. The anthropological and psychological literature makes it clear that without help from others, people cannot meet their material, emotional, and intellectual needs (Tomasello & Gonzalez-Cabrera, 2017). Trust is how people manage the risks associated with such high levels of interdependence (Cvetkovich & Lofstedt, 2013).

Almost every scholarly field has developed one or more theories of trust. This report will introduce two consensus varieties: identity-based trust and experience- based trust (Rousseau et al., 1998), focusing on the latter.

Sometimes, people choose to trust those with whom they share some kind of identity or affinity. For example, as a research psychologist, I tend to seek career advice from other research psychologists. This is identity-based trust. At many organizations, the marketing department manages identity-based trust by convincing people to see the organization as a likeable friend. For example, a children’s museum might market itself as a fun place where families feel welcome.

More often, people choose to trust those whom prior experience has shown are trustworthy; this is experience- based trust. Research shows that whether people are judging another person, an organization, or even a robot, they use the same five criteria when conferring experience-based trust: Competence, Reliability, Sincerity, Integrity, and Benevolence.

For example, I trust my hair stylist because she gives me great haircuts (competence) on every occasion (reliability); she is transparent about pricing (sincerity), which is consistent for everyone (integrity); and she both asks after my wellbeing and actively listens to my responses (benevolence). This report will look most closely at Reliability and Benevolence (see section Trust in Children’s Museums).

First, it is useful to summarize some of what Knology has already learned about trust from zoos and aquariums.

While zoos and aquariums are different institutions than children’s museums, all three play a role in the social, emotional, and cognitive development of children.

Further, all three institutions work to build trust as both mission-based organizations that serve their audiences (at least in part) through publicly accessible facilities.

Zoos and aquariums work to promote the conservation of wildlife and wild places. Typically, they rely on identity- based trust to gauge the credibility of their conservation messages: to learn whether their audiences believe their messages they instead ask whether those audiences like them (favorability) and feel attached (affinity) to them as places. This approach is not wrong, but it is incomplete. Although the conservation mission extends far beyond their facilities, people decide whether they trust in the institution’s conservation mission based on what the experience firsthand when visiting and what they hear about through their social networks

Theories of persuasion posit a much larger role for the criteria of experience-based trust (trustworthiness) in deciding whether to believe a message about conservation or any topic.

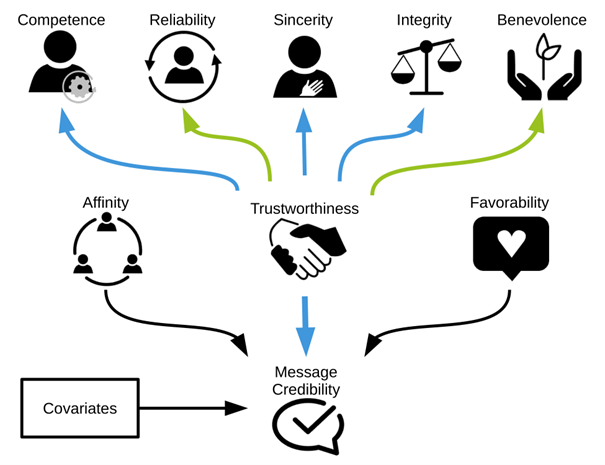

Figure 1. Model of how trust contributes to message credibility. Blue and green arrows show the contributions of experience- based trust. This report pays special attention to the contributions of the green arrows.

Figure 1 shows how the criteria of the two varieties of trust fuse into “epistemic authority”—i.e., whether people see you as a thought leader. The icons represent collections of behaviors the public judges when deciding whether to trust a potential thought leader. The arrows show the influence of epistemic authority on whether people believe the potential thought leader, i.e., believing the conservation messages that zoos and aquariums offer as potential conservation leaders.

Knology worked with zoos and aquariums to identify nearly one hundred behaviors that sampled every aspect of daily operations and mission-related work, including caring for animals, interacting with visitors and the local community, supporting staff, managing their finances, etc. (Voiklis, Gupta, Rank, et al., In Press).

We might call this activity “what is your trust fall?” In identifying these behaviors, Knology was asking zoos and aquariums to imagine each one as a piece of evidence for why members of the public should take the risk of trusting them. Two thousand people from around the U.S. participated in two surveys to assess the importance of these behaviors and how well zoos and aquariums performed them.

The results matched the theory: trustworthiness, with its five experience-based criteria, was the strongest predictor of message credibility. Identity-based trust criteria also mattered, but more so for specialized publics: For example, those who regularly sought out conservation news and likely identified as conservationists.

These findings from Knology on zoos and aquariums offer insights for the children’s museum field. Of course, children’s museums have a distinct trust profile that reflects their focus on children rather than conservation.

Further research is required to identify the key reasons behind children’s museums’ message credibility, as detailed with zoos and aquariums above.

Nevertheless, museum professionals can run an activity akin to the “what is your trust fall?” exercise. They can identify behaviors that provide the evidence their audiences need to assess trustworthiness. Virtual programming can provide evidence for almost every criterion of trustworthiness. Here, we focus on two criteria—Reliability and Benevolence—that audiences are likely to use when judging the trustworthiness of a children’s museum with which they are newly acquainted.

Children’s museums have long sought to reach audiences who cannot visit their facilities due to geographical distance and/or costs. Virtual programs, originally intended as an emergency response to the pandemic, help accomplish that goal. Continuing to produce virtual programming may tax resources for some museums, making these programs unfeasible. However, museums interested in sustaining virtual programming can use it as a way to cultivate the museum’s reputation for reliability and build trust with new audiences.

Producing virtual programming can also serve as evidence of goodwill for audiences who cannot otherwise access the children’s museum. Again, continuing to offer consistent virtual programming would further cultivate the museum’s reputation for benevolence.

Market research (e.g., Dilenschneider, 2020) shows people avoid museums after a negative experience, including a seeming “bait and switch” in programming. It is possible to repair a breach of benevolence (Xie & Peng, 2009), but the process is slow and resource intensive.

Research shows that trust is crucial to successful engagement by public institutions, although much work remains to be done on the specific trust profile of children’s museums. Museums can get a head start by assessing their exhibits and programs—including virtual programming—from the perspective of their audiences. Museums can ask what does this exhibit or program reveal about my Competence, Reliability, Sincerity, Integrity, and Benevolence? Research can then test whether audiences agree when deciding whether they trust children’s museums and believe their messages.

Cvetkovich, G., & Lofstedt, R. E. (2013). Social Trust and the Management of Risk. Routledge.

Dilenschneider, C. (2020, June 24). Why People Say They Won’t Visit Cultural Entities, COVID-19 Aside (DATA). Impacts Experience. https://www.colleendilen.com/2020/06/24/why-people-say-they-wont-visit-cultural-entities-covd-19-aside-data/

Field, S., Fraser, J., Thomas, U.G., Voiklis, J., & ACM Staff (2022). The Expanding Role of Virtual Programming in Children’s Museums. ACM Trends 5(1). Knology & Association of Children’s Museums.

Museums and Trust 2021. (2021, September 21). American Association of Museums. https://www.aam-us.org/2021/09/30/museums-and-trust-2021/

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so Different after All: A Cross-Discipline View of Trust. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 393–404.

Tomasello, M., & Gonzalez-Cabrera, I. (2017). The Role of Ontogeny in the Evolution of Human Cooperation. Human Nature, 28(3), 274–288.

Voiklis, J., Gupta, R., Rank, S. J., Dwyer, J. T., Fraser, J. R., and Thomas,

G. (In Press). Believing zoos and aquariums as conservation informants. Zoos & Aquariums in the Public Mind. Springer Nature.

Xie, Y., & Peng, S. (2009). How to repair customer trust after negative publicity: The roles of competence, integrity, benevolence, and forgiveness. Psychology & Marketing, 26(7), 572–589.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

Traumatic and tragic events in the news can deeply affect the children and families our field serves. As community resources and advocates for children, children’s museums serve the critical function of helping to build socioemotional supports for children and those who love and care for them.

In the words of Kansas Children’s Discovery Center President and CEO Dené Mosier, “It is our duty as a community to make sure our children are given a peaceful environment in which to heal and connect to community resources.”

Read on for resources from children’s museums on talking about and processing tragic events.

Talking With Children About Tragic Events

Boston Children’s Museum (MA)

“Some activities in the Boston Children’s Museum activity library are specifically aimed at promoting healthy coping mechanisms and self-expression during stressful times, which may be relevant for your family right now.”

Coping with Traumatic Events

Children’s Creativity Museum (San Francisco, CA)

“Parents and caregivers play an important role in helping children recover from the exposure of traumatic events. For a young person, coping with death and loss can be difficult, so we’ve assembled some trusted resources for how to talk with your child(ren) and family.”

Tips for Helping Children Cope with Tragedy

Children’s Discovery Museum of San Jose (CA)

“No matter what age or developmental stage the child is in, you can start by asking your child what they’ve already heard. Most children will have heard something, no matter how old they are. After you ask them what they’ve heard, ask what questions they have.”

Resources for Parents During News of Tragic Events

The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis (IN)

“We believe in the power of children to help change the world. The Children’s Museum is a place where all children and families can learn from one another—regardless of our differences. The core of our mission at The Children’s Museum is to help transform the lives of children and families. We hope these resources can be a starting point. Let’s partner with our children and help to make the world a better place.”

Community Resources

The Doseum (San Antonio, TX)

“Navigating tough topics with our children can be difficult—especially after a tragic event. Your support and care can go a long way in creating a positive impact in their lives as well as those around you. Our commitment is to continuously seek and share valuable resources to educate and assist the Community during these trying times.”

Helping Children Cope: Talking with Kids About Violence and Tragedy in the News

Minnesota Children’s Museum (St. Paul)

“When violent acts dominate the news, it can be hard to know how to talk to kids about such tragedies. The instinct for many adults might be to shield children from the scary or upsetting news.

“But kids are often more aware than we realize, picking up on body language and physical cues from grownups and absorbing information from their peers and surroundings. This can leave them scared and confused.

“It’s important for parents and caregivers to proactively talk to kids about tragic events when they happen. Adults can help kids put traumatic events into perspective in an age-appropriate way so that kids can understand and process the messages they are hearing. Having these conversations also helps establish a sense of safety while allowing children to work through emotions they are feeling.”

Resources and Letter from the Executive Director

National Children’s Museum (Washington, DC)

“At National Children’s Museum, our mission is to inspire children to care about and change the world. We truly believe that children can affect lasting change. Throughout history, children have been at the forefront of progress, and they are valued citizens who have inspired action. We encourage you to empower the young learners in your life to make their voices heard.”

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

By Dr. Michael Yogman

I may be a pediatrician, but it doesn’t take a doctor to know the last two years have been profoundly challenging for our nation’s children. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted all areas of children’s lives, including canceled playdates and school closings—all exacerbated by prolonged delays in vaccine eligibility for my youngest patients. Many children have lost caretakers and other family members and faced severe illness themselves.

Today, I write to the Association of Children’s Museums as part of the We Can Do This campaign—a collaboration among the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and many other organizations committed to the health and wellness of our nation and its children—that seeks to increase public confidence in and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines while reinforcing basic prevention measures such as mask wearing and social distancing.

The Association of Children’s Museums and its members are key partners in this effort. As the past board chair of the Boston Children’s Museum, I believe strongly in the vital role of museums in the effort to educate families about COVID-19. Museums promote hands-on, playful learning and discovery; cooperation; collaboration; and concern for all our fellow citizens. The work the association does is more important than ever, and I am grateful for our ongoing partnership.

The impact of COVID-19 on kids has been devastating. As of April 2022, one in six children under age 18 have been infected with COVID-19. Contrary to what some believe, children are not immune to the devastating effects of this virus. Over 100,000 have been hospitalized, and over 1,500 have died. It’s hard to fathom that scale of loss—the equivalent of 30 school buses full of kids. We are also concerned about the symptoms of long covid in children.

However, those numbers alone do not adequately illustrate the impact the pandemic has had on children’s health. One of the most alarming outcomes has been the mental health crisis that continues to unfold. In October 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association declared a national emergency in children’s mental health, writing:

As health professionals dedicated to the care of children and adolescents, we have witnessed soaring rates of mental health challenges among children, adolescents, and their families over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, exacerbating the situation that existed prior to the pandemic.

Fortunately, thanks to the tireless work of medical researchers, children ages five and older are now eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine that is safe, effective, and freely available for all families. The pediatric COVID-19 vaccine has been rigorously reviewed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which oversaw the participation of thousands of children in clinical trials and continue to monitor the safety and efficacy of the vaccine as we surpass 27 million vaccinated kids. Hopefully, the vaccine for younger children will be available soon.

To move past the pandemic, it is crucial that as many children are immunized against COVID-19 as possible. That requires us to concentrate our efforts on vulnerable populations by working together to reach them and supporting the immunization of all our citizens. This will not only prevent severe illness and death, but it will also help to keep classrooms open, allow kids to socialize with significantly lower risk of contracting serious illness, and help to protect children’s caretakers who may be in a higher risk category for severe illness and death from the virus.

Vaccinating children—along with deploying other basic prevention measures as needed—will protect their health and allow them to fully engage in all the activities that are so important to their health and development. As pediatricians, we are working directly with families to educate them on the importance of protecting kids from COVID-19.

Each of us has a role to play in protecting children against COVID-19. Museums are particularly important partners in this effort. Museums support education, promote empathy, and support caregiver–child relationships—all critical to buffering stress and promoting resilience. Despite being one of the hardest-hit institutions during the pandemic, museums and the work you do are more important than ever.

When museums were forced to close at the beginning of the pandemic, you did not abandon your mission to educate the public. Museums across the country, including the Children’s Museum Houston, the Children’s Museum of Manhattan, and my very own Boston Children’s Museum, began building out digital resources to provide accessible, free educational resources for kids. By inspiring curiosity in our children, museums are shaping a generation of young minds who can make informed choices, solve tough issues, and critically evaluate sound scientific advances. This is key to not only helping us move past the COVID-19 pandemic, but also preparing a generation to intervene in future public health crises.

Museums are also crucial in promoting empathy and concern for all our fellow citizens. When we wish to learn about other cultures, museums are often one of the first places we go, because they provide insight into the past, present, and future of ourselves and each other. Developing empathy and respect for one another is vital, especially when dealing with a public health crisis. For children, it helps them understand the sacrifices we make to protect others and reduces feelings of isolation and loneliness when times are tough.

Finally, museums provide a necessary space for introspection. Amid a mental health crisis, museums provide children and adolescents with a place to think, reflect, and develop informed opinions. Whether it’s reflecting on history or appreciating the beauty of the natural world, museums provide perspective and peace in a nonstop world.

The gifts that museums provide are timeless, but they are particularly invaluable as we work to respond to COVID-19 and to protect our kids. As a pediatrician, I urge museums across the country to continue prioritizing education, empathy, and introspection. You can help us in our work by continuing to innovate on delivering virtual learning opportunities for families and providing COVID-safe physical spaces for children to learn. It takes all of us together to prioritize children’s health and well-being during such an uncertain time.

Museums are key allies in the work we do, and we are grateful for their partnership as we work together to create the next generation of educated, informed citizens. Check out WeCanDoThis.HHS.gov for resources museums can use to help with your COVID vaccine education and outreach.

Click here to hear more from Dr. Yogman about the relationship between museums and the fight against COVID-19.

Dr. Michael Yogman is a leading Boston area pediatrician, Immediate Past Board Chair of Boston Children’s Museum, and Fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 5.2, the second report in the fifth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

For this ACM Trends Report, we invited Scott Burg from Rockman et al to write about his team’s research during the pandemic around parents and caregivers’ preferences for virtual programming by children’s museums. Scott was a speaker at a discussion forum with ACM members focused on virtual programming in October 2021 (See ACM Trends Report 5.1 for details).

Due to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, museums had to make critical decisions about conditions for opening and closing as well as virtual programming based on limited evidence. This shift left children with limited options to engage socially with peers and an increased reliance on parents and caregivers to manage school activities and after-school opportunities. One outcome of the pandemic was an increase in online museum offerings, many of which were targeted at children.

Most museum studies during the pandemic focused on health and safety concerns and returning visits (e.g., mask wearing, social distancing, capacity levels, etc.). This report focuses on results of a study of the potential value of continuing to offer virtual learning activities following the physical reopening of museums. Researchers at Rockman et al (REA) wanted to learn what parents and caregivers felt about children’s museums’ virtual programming, and the types of virtual programs that children’s museums could develop to address families’ needs, interests, and concerns.

In the fall of 2020, REA collaborated with the Children’s Creativity Museum in San Francisco to survey northern California Bay Area children’s museums. The survey collected parent and caregiver feedback on the types of virtual programs they would like to see for their children. Following the first wave of data collection and validation of the instruments, a second wave expanded the research opportunity to other institutions in the Association of Children’s Museums (ACM) network (https://bit.ly/REA-ACM_Blog). In total, 13 different children’s museums across the country distributed the survey to their members and mailing lists.

The REA study focused on understanding the types of virtual programming that parents and caregivers want from children’s museums. Their preferences for types of virtual programs might be influenced by a child’s school or care situations, child age, amount of screen time, cost, and other factors. Each participating museum received real- time access to aggregate study findings as well as their own museum’s individual data through customized digital reports.

Between November 2020 and January 2021, REA gathered more than 1,200 responses from museum patrons. Not all survey respondents answered every question. The bulk of respondents were parents or caregivers of children aged 2-7 (Figure 1). School and care situations varied among participants’ children, spanning those attending school or daycare in person; and those attending virtually either in a hybrid solution (in-person and remote) or being homeschooled or cared for at home (Figure 1).

We found that parents and caregivers’ interest in virtual programs was mixed. About half of all respondents said they had “no interest” or “slight interest” in virtual programs. The other half expressed “moderate” or “high” interest (Figure 2). One overriding concern for participants was the amount of screen time their children were already exposed to. One in five respondents reported that their child spent more than three hours each day on a computer or digital device. Surprisingly, more screen time did not coincide with less interest in virtual programs. These findings suggest that everyone’s threshold for screen fatigue is different.

Our survey showed a correlation between parents and caregivers’ interest in virtual programs, and the type of schooling or care their child was receiving at the time of the survey. Parents and caregivers of children who attended school or daycare in-person were less interested in virtual programs than those whose children were being home-schooled, attended school online or were in a hybrid situation (Figure 3). A child’s age was not related to their parent or caregiver’s interest in virtual programming, suggesting that these issues are based on values rather than a common consensus on developmental concerns.

Despite concerns about screen time, the survey results showed that many parents and caregivers wanted to reconnect with their local children’s museum. They also wanted to replicate museum experiences either at home or in a remote environment.

Parents and caregivers prioritized museum approaches in both virtual and in-person settings that:

Parents and caregivers also indicated an interest in programs that offered the kinds of experiential learning that children’s museums succeed at. These included programs that actively engage participants (e.g., science, art) vs. activities that are more passive (e.g., read alouds, learning study skills). Parent and caregivers were not interested in activities that duplicated virtual school lessons. Nearly three-fifths of respondents said they would consider paying for virtual programming.

Most parents and caregivers preferred virtual programming scheduled on weekends. They indicated a slight preference for weekday virtual programming that allows independent child participation (Figure 4).

The survey did not reflect the many opportunities for children’s museums to educate parents and caregivers on methods to regulate and participate with their child’s virtual learning activities. Research suggests that when parents and caregivers participate and scaffold their children’s activities (asking questions, extending play), this results in higher retained learning (Takeuchi and Stevens, 2011).

Anxiety over prolonged screen time can undermine this type of support. What it means to be an effective ‘digital parent’ can be perceived as contradictory, as parents and caregivers try to minimize the negatives of screen time while benefitting from the affordances of the technology.

Parents and caregivers need support to better understand the content of what their children watch and do on screens, the context of where they watch and do, and the connections they make (or do not make) while watching and doing (Livingstone et al, 2017).

This integrated approach provides more insights into the positive or negative impact of digital media use than a simple measure of time. Parents and caregivers need to be encouraged to think critically about how to support positive uses and minimize negative consequences. This is where children’s museums can play a valuable role.

As the pandemic restrictions are lifted, the needs and expectations of museum audiences will evolve. This survey provided insights into the minds of audiences during the fall and winter of 2020, and but cannot predict what else may change as schools and museums continue to reopen. These data provide some insights that can support analysis and monitoring of how virtual programming is valued in the future.

To put these findings to work, virtual programming offered by children’s museums can respond to these key takeaways:

Are parents and caregivers tired of virtual programs, or has remote learning become a mainstay of education? Is virtual programming enabling visitors to form a new kind of relationship with children’s museums? Can museums use virtual programs to extend their reach to underserved audiences, increase access to diverse communities, or add value to their institutions as trusted sources of information and learning? Where could collaboration between children’s museums or between museums and school districts strengthen both the informal and formal education landscape? What role can researchers and evaluators play in facilitating this discussion?

To answer those questions and build on this study of virtual programming that parents and caregivers want from children’s museums, the researchers hope to expand the number of institutions involved in any future studies to ensure the data are representative and determine if regional variation or museum size influence perceptions. Ideally, future research will recruit a more inclusive sample of community participants including parents and caregivers who may not visit children’s museums regularly or do not have access to virtual programming.

We also hope to encourage the development of research- practice partnerships, which can serve as a critical tool for generating actionable data that children’s museums need to navigate the post-COVID world

Field, S., Fraser, J., Thomas, U.G., Voiklis, J., & ACM Staff (2022). The Expanding Role of Virtual Programming in Children’s Museums. ACM Trends 5(1). Knology & Association of Children’s Museums.

Takeuchi, L., & Stevens, R. (2011). The new coviewing: Designing for learning through joint media engagement. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

Livingstone, S., Lemish, D., Lim, S. S., Bulger, M., Cabello, P., Claro, M., Cabello-Hutt, T., Khalil, J., Kumpulainen, K., Nayar, U. S., Nayar, P., Park, J., Tan, M. M., Prinsloo, J., & Wei, B. (2017). Global Perspectives on Children’s Digital Opportunities: An Emerging Research and Policy Agenda. Pediatrics, 140(Suppl 2), S137–S141.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

By Kim Koin, Chicago Children’s Museum

Chicago Children’s Museum (CCM) closed its doors to the public in March 2020 to help stop the spread of COVID-19. Like many learning spaces, CCM needed to switch from in-person to online interactions to continue connecting with our community during the pandemic. Museum educators soon began making videos at home, building upon our best practices for interacting with guests at the museum. Here are some tips gained by staff that we hope other museum professionals can use and adapt for your online programming!

Setting up a shot to film on the floor, complete with a stack of books. A selfie stick angles the phone camera down, and a book is placed on top to keep it steady!

Prep: Give yourself LOTS of time to figure things out beforehand. Museum professionals already know the importance of planning your workshops and activities. This is especially important when there’s a digital component to your programming. For a five-minute video, consider that you’ll need to create a concept, gather and test materials and processes, write a script, set up the camera, and do numerous dry runs.

“Camera” & audio set up: Filming was new for many of us at the museum. We spent time experimenting with our smart phones, thinking about framing, background noise, and prototyping.

Framing the shot: In this photo, many of the items on the table are going to be obscured by the captions. All the materials should be moved up a few inches.

Action: Before we began creating content at home, we museum educators were used to being in front of a crowd—but not a camera! We had to learn how to do a few things differently. However, our core facilitation style stayed consistent.

Though there can be some shyness to overcome, try to focus on the way you would facilitate without a camera in front of you. What’s your teaching style? How do you like to engage your students and audience? Use the same tone, sense of humor, playfulness and “voice” that characterizes you when you are facilitating in-person at the museum. By being yourself, your virtual facilitation will be most natural and engaging.

Last tip: Take a deep breath and smile—you’re doing great!

Kim Koin is Director of Art & Tinkering Lab Studios at Chicago Children’s Museum.

By Bob Harvey

NOTE: I recently received a request to comment about fundraising during the COVID-19 experience, specifically around the topics of donor communication and cultivation strategies. I decided to use this request as an opportunity to speak with several of my current and former colleagues and then I created the following summary. (By the way, this group has about 300 years of experience in fundraising circles.)

Relationship building is the very foundation and core of nonprofit development. Both donor communication and cultivation strategies fit nicely under the relationship building umbrella.

First, let me assure you that people, foundations, and corporations are giving. Two of my firm’s clients have received $500,000 contributions in the last two months, one of real estate and one in cash. A third (a developing children’s science museum) just received notice of a $6.1 million federal grant that was submitted two years ago!

Remember, nearly 70 percent of all giving is from private individuals, not foundations, grants, and corporations. Why are they still giving? First and foremost, “People give to people more than they give to causes.”

The most productive solicitation is, “The right two people, calling on the right prospect with the right story and the right ask.”

You might be tempted to say the economy is so disrupted that people aren’t going to give and if they do, they will give less and be reluctant to make a pledge.

There is no indication that is true. If you look at individual giving, much of the money is in the form of “discretionary funds” that are most often generated by invested wealth. Even today, the stock market continues to reach record highs.

If you consider corporate giving, many U.S. firms have received “bail-out money” in the form of emergency funds. Others are formally committed to 5 percent giving levels. There are also have divisions of national and international corporations. They are giving.

When you consider private foundations, most have a legal and moral obligation to continue with funding deserving projects. They are giving.

The fact is that funders and donors are looking for progress and new programs. They are urgently seeking you.

So how do you go about developing a solid “relationship building” program?

First, review and evaluate your existing donor records. This is true no matter what system you are using to develop a list of bona fide prospective donors.

What does your analysis tell you? In relatively recent history, have any of your prospective donors indicated interest in your mission? Have you had meaningful communication lately? If not, why? What are you going to do to make them your friend or renew the relationship?

How accessible are these prospects? Remember the “right person” requirement? That person might not be on your board or immediately available to you. You must contact them, inform them and educate them, and then ask for their assistance in setting up a meeting with the prospective donor. But don’t make that call until you have already solicited your new friend, donor and volunteer.

The fact is that the public, in general, wants to learn more about children’s museums. They want to know what STEAM is all about. After all, it’s relatively new. It’s exciting. It’s science, AND KIDS, for Pete’s sake!

Children’s museums are most often thought of as being in the education industry, but I believe we more correctly belong in what is collectively called the hospitality industry. Why? We are providing goods, services, and experiences to the public. We are competing for the discretionary dollars that are generated when the consumer makes a decision to do “this” rather than “that.” We must provide a positive experience for those who choose us. We are competing with all of the other diversions, appeals, and activities. We are competing for the public’s attention, participation and funding, and we’re only going to be successful if we are better at what we do.

Children’s museums should form relationships with many different networks to remain fresh and fascinating. We are vital components in economic development. We impact tourism and lodging. We should network more closely with the educational systems in our market area. We should also talk frequently with local manufacturing concerns about what we need and ask for their help for in-kind donations. Plus, there is an ongoing need to be on the lookout for new opportunities for sponsorships of programs and exhibits.

Relationship-building can lead to some unexpected—but successful—partnerships. Recently, my firm encouraged a developing client to make a presentation to the leadership of a huge military airbase in their market area. Most of the board members said “Why?” The answer was easy. You see, there were several thousand air force personnel on that base and most of them were looking for something new and rewarding to get involved in.

We contacted the base and explained what we were doing. Since there was a huge contingent of technology-based personnel there, we told them we would welcome their participation in brainstorming, designing, and building new exhibits.

The word went out and, guess what? More than 300 people responded “yes, I’ll help.” The base commander said they would be willing to help financially.

There is never an end to relationship building. You can get new people and energy involved simply by asking for their short-term assistance. Sometimes you have a need for a particular skillset for a particular task. Sometime it’s as simple as needing someone who lives in a distant location to help with conducting an outreach program.

In these peculiar times, it is sometimes wise to consider reevaluating your development strategy. One of our clients recently agreed to take their big, relatively clumsy project and break it down into “phases.” These bite-sized phases were more easily understood. Hitting a series of smaller goals demonstrated success and progress. Ultimately, they hit their $2.9 million goal in the same amount of time it would have taken to labor through the larger strategy that required individual giving at a much higher level. Remember, your future requires you to continually seek out the smaller gifts too. It is those gifts that grow up to become major gifts later on in your relationship with the donor.

Exhibit sponsorships are related to fundraising—though they are not always considered as such. For those children’s museums working with exhibit or display sponsorships, we are learning that it is not a good idea to give “lifetime” sponsorships. It appears that the right amount of time is about five years for sponsorships, particularly for those of $500,000 or more. Why? Every display has a lifetime. They will eventually need to be renovated or retired. Five years seems to be the right number. Donors don’t seem to consider that five year term to be too short or otherwise inappropriate, particularly if your signage and recognition programs allow for long-term recognition, even after the exhibit is retired.

At some appropriate time in your development curve, it would be wise to conduct three studies:

In many cases, the Community Attitude and Fundraising Feasibility Studies can be accomplished with a single effort.

For best results, these studies should be conducted in that order, and each should be done by a professional firm. Why? There is no validity to the outcome of any of these studies if it isn’t conducted in such a manner as to ensure honesty, confidentiality, or objectivity. Your community leadership will not speak frankly about your programs, services, and leadership when they are concerned about “who is going to hear what I am saying?” Responses need to be solicited, recorded and reported without compromising confidentiality and that is best accomplished through an “outsider.”

Now, go out and build a new relationship or resurrect an old one.

Bob Harvey is CEO and President of Bob Harvey Associates and vice president and COO of Harvey Nonprofit Development. An industry leader in fundraising since 1974, his string of successful campaigns include clients in healthcare, environmental causes, animal organizations, education, history and arts. He can be reached at bob.harveyassoc@gmail.com.

The following is an excerpt from “Hawaii Children’s Discovery Center … The gathering place – where East meets West” by Loretta Yajima. It is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge/CRC Press in International Thinking on Children in Museums: A Sociocultural View of Practice by Sharon E. Shaffer on October 12, 2020, available online.

Incorporated in 1985, the Hawaii Children’s Museum was the first and only museum in Hawaii designed especially for children. Its mission: to bring information and experiences about the world beyond our Island shores to the children of Hawaii and to instill in our keiki a pride in themselves and their ethnic and cultural heritage. By offering audiences of all ages a wide variety of experiences in a world-class participatory learning environment, it was our hope that this would be a place that inspires and educates both the young and the “young at heart.”

In 1988, the organization, led primarily by a small group of volunteers, raised the funds to construct an initial temporary facility in the Dole Cannery Square, space donated by Castle & Cooke Properties. The museum celebrated its grand opening at its 5,000-square-foot site on January 24, 1990. It immediately proved to be a popular gathering place for Hawaii’s families. Where else in Hawaii could children learn about science, the human body, culture, and communications while having fun? Where else in Hawaii could parents participate in self-discovery activities with their children in a creative yet nurturing environment?

The demand for services by school and community groups was so great that the facility was obviously not suitable for the long-term development and growth of the museum. Relocation to a larger, permanent site was deemed a priority. After considering many options, then Governor John D. Waihee offered a site in the State’s newly developing Kaka’ako Waterfront Park with the idea that the museum would serve as the anchor tenant for the area. The plan was that the park would become a gathering place for Hawaii’s families as well as for tourists who came to visit Oahu.

So, out of the “ashes” of an old city incinerator was born a dream – literally. To say that the story of the Hawaii Children’s Discovery Center is a unique one would be an understatement. In 1998, the newly developed Children’s Discovery Center rose from the renovated and expanded shell of an old incinerator next to a city landfill near downtown Honolulu. With the support of government officials, major corporations, and the community at large, millions of dollars were raised for the construction of a permanent facility. The 38,000-square-foot incinerator was renovated and transformed into a world-class children’s museum – a remarkable feat considering Hawaii’s economy was in a prolonged slump at the time and funding was scarce.

The former Kaka’ako landfill was transformed into a gem of a waterfront park, and the former city incinerator became a beehive of activity for children from across the Hawaiian Islands. The Hawaii Children’s Discovery Center, the first and only museum of its kind in Hawaii, was known largely through word of mouth and its growing reputation as a world-class children’s museum. Local families, school groups, and tourists flocked to the museum, which quickly grew to serve over 125,000 visitors a year. While many children’s museums typically start out in donated space, Hawaii’s children’s museum has the unique distinction of being the only one in the world that started out in a pineapple cannery and ended up in a city incinerator.

The first and only children’s museum in Hawaii dedicated to serving the children and families of the state, the Center’s mission remains to provide an interactive learning environment that will motivate and inspire children to new heights of learning and discovery. Through galleries of hands-on, interactive exhibits and educational programs, the Center helps children develop positive self-concept in a nurturing environment where children can learn through play. Here they can develop an understanding of themselves and others in Hawaii’s multicultural community and have a “window to the world” beyond the beauty of the island shores.

The Center serves children of all ages, abilities, and origins. It hosts a culturally and economically diverse audience throughout the island state, as well as a broader audience throughout the country and world. An educational resource for young children, the Center enhances and extends learning opportunities that children have at home or in the classroom.

While there are many outstanding children’s museums across the nation, the Discovery Center in Hawaii is unique in its focus on Hawaii’s history and rich cultural diversity. Its hands-on, child-oriented, carefully designed exhibits say to the communities’ keiki o ka aina (children of the land), this is a place about them and the people of Hawaii, about what they share in common, about who they are and where they came from.

The Center’s cultural galleries are, first and foremost, about the experience of discovery, about Hawaii’s immigrant population, and about the one common denominator that is shared by all, whether one lives in the middle of the Pacific or along the stormy shores of New England: It is about the immigrant’s need and search for community and hope. Theirs were voyages of discovery and wonder, similar in many ways to the daily experiences of the thousands of young children from throughout Hawaii and from all over the world, who visit the Discovery Center every day.

What makes the Hawaii Children’s Discovery Center unique is its focus on the cultural mosaic that is Hawaii: the history of its people, the challenges they faced as newcomers to a strange land, and the successes they achieved despite overwhelming odds; the celebration of their music, dance, food, ceremony, and commitment to each other; and the unique overarching community they created in spite of language, cultural, and prejudicial barriers. The Center and Hawaii’s children are indeed Hawaii’s “rainbow connection to the world.”

The Children’s Discovery Center has matured and fulfills its mission of being Hawaii’s “rainbow connection” to the world, each and every day. As the inspiration and model for the early childhood education movement that is taking place in China today, Hawaii’s very own children’s museum continues to be respected and admired by children’s museum colleagues both nationally and internationally. In 2017 the Center hosted the Asia Pacific Children’s Museum Conference, an international gathering of children’s museum professionals, in Honolulu. Most importantly, early education in the Islands has no stronger advocate and ally than the Children’s Discovery Center, and we are proud of the learning opportunities it provides to our young children and their families.

Loretta Yajima is Chair of the Board of Directors of Hawaii Children’s Discovery Center.

Sharon E. Shaffer is a museum consultant specializing in providing programming to younger children and works with museum professionals around the world. She is a former Executive Director of the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center, USA, and is the only educator ever to receive the Smithsonian Institution Secretary’s Gold Medal for Exceptional Service. She has a PhD in Social Foundations of Education and is an adjunct faculty member with the University of Virginia.

Jump to a Section

Opportunities for Culturally Relevant Practice in Museums, Cultural Competence Learning Institute

Embedding DEAI in Strategic Planning, High Desert Museum

The Three Bears Model: Identifying Just Right Partnerships, Chicago Children’s Museum

Mobilizing Your Museum to Be a Resource for Equity, Cincinnati Museum Center

Conclusion and Resources

In the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, museums—like so many other institutions and sectors—are being asked to reimagine themselves: Will hands-on exhibits ever be the same? When and how can we reopen safely for our staff and our visitors? In the face of these existential questions, how can we keep equity front and center?

CCLI (Cultural Competence Learning Institute) is a partnership between Children’s Discovery Museum of San Jose, the Association of Science and Technology Centers, the Association of Children’s Museums, and the Garibay Group. On May 19, CCLI hosted the webinar, “Reopening with Equity in Mind: Opportunities for Culturally Relevant Practice in Museums.” CCLI operates on the idea that success for museums in the 21st century will depend on embracing organizational change, allowing organizations to meaningfully connect with their community.

Cecilia Garibay, President of, Garibay Group shared a framework for grounding DEAI efforts in concrete areas of operations for rebuilding with an equity lens, drawing from CCLI’s National Landscape Study: Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion (DEAI) Practices in Museums (Garibay and Olson, forthcoming).

| CCLI’s key definitions surrounding equity work: • Diversity encompasses all those differences that make us unique, including but not limited to race, color, ethnicity, language, nationality, sexual orientation, religion, gender identity, socio-economic status, age, and physical and mental ability. A diverse group, community or organization is one in which a variety of social and cultural characteristics exist. • Equity acknowledges differences in privilege, access, and need, and supports space for appropriate adaptation and accommodation. • Inclusion denotes an environment where each individual member of a diverse group feels valued, is able to fully develop his or her potential and contributes to the organization’s success. Find more definitions at the CCLI website. |

Garibay noted that the concept of equity can often feel abstract and even aspirational, but when we recognize that structural and historical barriers and systems of opression are at the root, it allows us to consider how we can begin to affect and change those systems and structures. She described how organizational change frameworks that look at systems and operational structures can help to create and measure change toward DEAI. The Burke-Litwin Causal Model of Organizational Change (Burke & Litwin, 1992; Martins & Coetzee, 2009) identifies three interrelated “factors” for change:

Garibay pointed out that DEAI efforts often focus on the personal level using diversity workshops, implicit bias trainings, and other methods to support individual on their cultural competence journey. These strategies, however, ignore institutional levers critical for sustainable change and informing equity-focused organizational practices.

“I want to start by making it clear what an opportunity all of us have ahead of us. Our organizations are going to be community responders. Our first responders have been out there saving lives. And it’s our turn to move in when we can reopen as community responders to the pandemic, getting ready to help rebuild community and connection.”

Dana Whitelaw, High Desert Museum

Museum leaders from CCLI alumni organizations offered reflections on how they are thinking about equity amidst this pandemic.

Dana Whitelaw, Executive Director, High Desert Museum (Bend, Oregon)

The High Desert Museum, an interdisciplinary museum in Bend, Oregon, grounds all areas of their operations in an equity lens, both internally and externally. Dana Whitelaw discussed how this affects her museum’s strategic planning and approach to staffing and skilling up.

Pandemic Strategic Plan: The museum has created a pandemic strategic plan that sits alongside their pre-existing five year strategic plan. They have three phases over the next 12-18 months:

During this time of closure, the museum is working to embed equity into all facets of reopening:

Admissions: How can your museum ensure access for a wide audience after reopening? Existing access programs, such as Museums for All, rely on walk-in admissions. If we reopen using timed ticketing, online sales, and cashless payment, how will our front desk processes continue to have an equity model?

Membership: Membership is seen as a privilege – how can we make it accessible?

How can you use membership to build more access? The High Desert Museum is working with partner organizations, starting with our hospital, to gift a community membership to frontline workers (e.g. nurses and grocery store workers) for each new or renewed membership.

Programming: How can you ensure your upcoming programming is inclusive?

The High Desert Museum is collecting stories from the pandemic experience for a future exhibit. They’re reaching out to community partners to ensure they feature and include a diverse set of stories.

Staffing: How can you skill up your staff to align with community needs?

You can build an equity approach into all levels of your organization. With governance, what board-level skills are needed for reopening? With staffing, how can you scale up to be relevant and responsive to new community needs?

Jennifer Farrington, President and CEO, Chicago Children’s Museum (Chicago, Illinois)

When Chicago Children’s Museum closed its doors due to COVID-19, it could not fulfill its mission to promote joyful learning by serving children and families to the museum in the same ways it had done before. President and CEO Jennifer Farrington shared how the museum identified new strategies to meet their mission, by authentically leveraging local partnerships to distribute resources to their community.