| This article is part of the “Children’s Museums and Climate Change” issue of Hand to Hand. Click here to read other articles in the issue. |

By Charlie Trautmann, PhD, Cornell University

Many children’s museums are thinking about whether to introduce the difficult but increasingly important topic of climate science into their programs. They are looking for guidance not only on where to start, but does it make sense for their primary audience of very young visitors. Will preschoolers even remember anything about this complex and sometimes scary topic?

Whether the purpose of a visit to a children’s museum is education, relationship-building, entertainment, or some other goal, the visit often involves making memories. When museum professionals understand the basic elements of how human memory works, they can design for the types of memories they want children and families to have when developing experiences for their audiences.

Before we apply the science of memory to museums, it is helpful to understand the time element of memory. Psychologists use three timeframes when discussing memory: sensory, short term, and long term.

Sensory memory is ultra-short, ranging from a few milliseconds to seconds. Our five senses provide information continuously, and most of it cannot be processed fully or stored (Sperling 1963; Orey 2021a). The image of a giant robotic dinosaur, the sound of the spark from a Van de Graaff generator, or the voice of the staff member who asked us not to run are all sensory memories. Some sensory information does survive and moves to a different part of the brain, becoming retained in short-term memory.

Short-term memory, also called “active” or “working” memory, lasts for only 20-45 seconds (Miller 1956). We have a relatively small capacity to keep information in working memory, with a limit of five to nine items, and so after sensing something, we need to do something with the information, or it will be lost (Miller 1956).

Some short-term memories become preserved, or “consolidated,” into long-term memories (Dudai et al. 2015). Long-term memories can last a lifetime. However, since short- and long-term memories occur in different parts of the brain, a transfer of information is required. In many cases, consolidation takes place during sleep. Key Point #1: Getting adequate sleep promotes improved memory (Ruch et al. 2012).

To describe five common types of long-term memory, psychologists usually divide them into two groups: conscious and unconscious, as shown below in Figure 1 on preceding page (adapted from Saylor Academy 2012).

Conscious Memory: Conscious memory involves consciously recalling information, such as what that happened a minute ago, or last year, or what two plus two equals (Cherry 2020). Within this broad category, episodic memory is recalling specific personal events, such as the time, place, and description of something that happened to us. Can you remember your first kiss or the senior high-school prom? These are episodic memories. In contrast, a semantic memory is a piece of general knowledge that has no specific time or place associated with it, such as “dogs have four legs” or “grass is green.”

The two types of conscious memory interact: semantic knowledge often starts as a sensory experience and becomes an episodic memory for a period of time. The child who releases a blown-up balloon taped to a straw on a string experiences the phenomenon of jet propulsion, which might stick in her mind as an episodic memory for that day. Eventually the time and place will become lost to her, and the concept of Newton’s Third Law—that “every action has an equal and opposite reaction”—will just become part of her general (semantic) knowledge about the way the world works.

On the other hand, episodic memory relies on our framework of semantic knowledge: the more we know about a subject, the more likely we are to be interested in further learning about it, paying attention to new sensory information that comes to us, and remembering it. The young boy who can watch birds at a window feeder during breakfast is much more likely to engage with an exhibit about the migration of birds at the museum. Key Point #2: Episodic memory and semantic memory can support each other.

Another important fact is that most humans have few episodic memories before the age of four or five. This universal phenomenon, called “infantile amnesia,” means that although children hungrily learn from the time of birth, young children are unlikely to reward their caregivers or museum educators with descriptions of their learning experiences.

Unconscious memory: In contrast to conscious memories, unconscious memories, also called “implicit” or “automatic” memories, are those that we don’t think about on a conscious level (Squire and Dede 2015). These kinds of memories are also important, because they influence our actions and behavior. Three primary types of implicit memories are of particular interest to museums.

Procedural memory refers to motor and cognitive skills that allow us to walk, talk, ride a bike, or type without consciously thinking. Children’s museums provide many opportunities, particularly for children with the fewest opportunities, to develop their procedural memory. In designed spaces, early learners can develop and practice gross motor skills, fine motor skills, observational skills, and sensory perception, often in ways they can’t at home. Although some would consider such activities frivolous, children at play are often testing their theories about the way the world works and, in so doing, are developing the foundations of scientific thinking (Gopnik, Meltzoff, and Kuhl 1999). Key Point #3: It is important that we emphasize the concept of learning through play to our stakeholders, and particularly to funders, who sometimes balk at the idea of supporting “play” with their funding.

Priming refers to how recalling information from one domain can trigger memories in another domain. In other words, by strategically activating knowledge in one area, we can use that activated knowledge to elicit knowledge in another area. Staff and volunteers can use priming questions with museum visitors, activating their prior knowledge—perhaps in an unrelated field—as a way of engaging them with a topic (Tulving and Schacter 1990).

Classical conditioning, the third kind of unconscious memory was discovered by Pavlov, who found that one stimulus can become associated, through repetition, with an unrelated stimulus that has a specific response (Cherry 2019). In his famous experiment, Pavlov rang a bell when feeding dogs, and this feeding caused them to salivate. Eventually the dogs would salivate whenever he rang the bell, even if no food were present. Marketers employ classical conditioning when they associate a logo or audio jingle with a pleasurable experience; the McDonald’s jingle can conjure up images, thoughts, and even smells of burgers and fries on the radio. Museums seeking to evoke positive thoughts and increased visitation can use their sounds, logos, and other images in much the same way.

Now that we have an understanding of the common types of memory, let’s apply it to a current topic of interest to many children’s museums: climate change. How can we prepare our children for the future without: 1) boring them with semantic knowledge about the climate they will largely forget, 2) traumatizing them with episodic memories of climate change in a way that scares them and prevents them from connecting with the topic, or 3) conditioning them, through repetition, to simply ignore or shut down on the topic of climate change?

One approach is first for children’s museums to capitalize on their ability to inspire relationships among people, objects, places, and concepts. As poignantly expressed by Baba Dioum, “In the end we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand, and we will understand only what we are taught” (Valenti and Tavana 2005).

Museums are well-positioned to inspire a child’s love for the natural environment by creating positive semantic memories about animals, places, water, and other elements of the environment that will last a lifetime. These positive memories about the environment can form a foundation to support later learning about the environment and its key systems, in a way that is age-appropriate and in line with a child’s cognitive learning abilities.

Second, through their programs and exhibits, children’s museums can encourage children to improve their critical thinking skills, which are important in countering much of the disinformation about climate change. Museums can help children become more comfortable in asking good questions, and simultaneously building children’s confidence to seek help from adults in answering their own questions. Museums can advance these goals by helping adults understand how children learn and form memories so that they can support childhood learning most effectively.

The science of climate change is complex. Many children’s museums struggle with the decision to include it at all for their primarily very young audiences. What engaging activities related to climate change could be presented in a playful way that a four-year-old would even remember? But as many other authors in this issue have stated, the early years are the optimal time for laying a learning foundation of critical thinking skills and building a sense of wonder and appreciation for the natural world, which in time, can blossom into a conservation mindset. By understanding how memory works, children’s museums can enhance learning and other positive impacts for the children and families they serve. Positive episodic memories and semantic memories can enhance each other, and museum educators can use this understanding to create the most effective programs and exhibits.

Charlie Trautmann is an adjunct associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Cornell University. He is director emeritus of the Sciencenter of Ithaca, New York, and a past board member of the Association of Children’s Museums and the Association of Science and Technology Centers. At Cornell, he teaches Environmental Psychology and directs the Environment and Community Relations (EnCoRe) Lab. He can be reached at cht2@cornell.edu.

| This article is part of the “Children’s Museums and Climate Change” issue of Hand to Hand. Click here to read other articles in the issue. |

By Stephanie Shapiro and Sarah Sutton, Environment & Culture Partners

Culture Over Carbon is a research project designed to improve the museum field’s understanding of energy use by examining data from five types of museums (art, science, children’s, history, and natural history), plus zoos and aquariums, gardens, and historic sites. The two-year research period, which began in September 2021, will cover at least 150 institutions in all geographic regions of the United States, spanning varying sizes and types of buildings (e.g., office vs. collection storage). The project will collect enough information to establish an energy carbon footprint estimate for the museum sector, while creating individual “roadmaps” to help participating institutions understand and use energy more efficiently. Resulting aggregate data will boost the cultural sector’s broad understanding of its current energy practices and help to plan for future expected changes in energy availability, policies, and regulations.

Culture Over Carbon is funded by a National Leadership grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to the New England Museum Association, which leads the project in partnership with Environment & Culture Partners and the nonprofit energy consultants New Buildings Institute (NBI).

Very few museums have the ability or resources to monitor and assess their own energy use, especially during this prolonged period of economic stress due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet without this data they are unable to make strategic energy management decisions to save money or reduce the greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) that worsen the climate crisis.

Museum staff interested in benchmarking their energy use and comparing use reductions struggle with the lack of comparisons. While the Leadership for Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) building certification program and the Environmental Protection Agency’s EnergyStar program provide energy performance ratings for buildings, there is no comparison framework/Energy Star score specifically for museums. (There are too few museum-user entries to create appropriate comparisons from a broad base of information.) Museums can join the International Association of Museum Facilities Administrators, which provides access to comparative data from about 200 institutions, but at a cost. Even with this information, staff and leadership often still struggle with how to make good energy use choices and how to pay for them, especially when they may require sometimes costly changes to existing operations.

Nearly every other major US sector understands that its energy use impacts the climate in some ways and has paths to strategically reduce their emissions. Without this context or guides to implementation, it is difficult for museums to find the means to make these shifts. As codes and regulations change—and budgets get tighter—museums need a strong case for competing for public and private funding for compliance.

The Culture Over Carbon project seeks to build a research foundation by focusing on the following questions:

The climate challenge is so significant that all who can possibly participate in creating solutions must do what they can. Until now, the museum sector has done little research on its own energy use, spent little time looking ahead to predict changes, and has expended minimal effort into articulating the need for investment in our energy systems to make better decisions. As nonprofit institutions, many museums recognize that they have a mission-driven responsibility to limit negative impacts of their work while modeling thoughtful, responsible behavior. Recognizing our fiduciary responsibility, this project tackles both the global and institutional issues that are so important to our futures.

Participating museums provide general building information describing their building design and construction, and how it is used. Based on their submission of twelve months of past energy use data, they will receive a profile of their site which prioritizes areas of concern and provides a roadmap of next steps, including working with an energy technician or engineer to achieve results. Many are eligible to receive a stipend for sharing their data.

Using all the data collected during the project, NBI will create a free report that identifies the variety and extent of energy formats and uses in the museum sector, comments on the most common areas for improvement, and offers recommendations for how the field can collectively reduce energy use that contributes to global warming.

Culture over Carbon participants share their energy use data through Energy Star Portfolio Manager (ESPM), a free online software program provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Anyone running a home or a building can use ESPM to understand how much energy is used on a monthly and yearly basis, and what the GHG emissions are. Many museums of all types or sizes already use ESPM for budgeting and managing energy consumption. However, the Carbon Over Culture project will move beyond this basic level by processing the data through First View, a software program developed by NBI with EPA funding to explore the research questions stated earlier.

If you are interested in learning more, please contact Sarah Sutton (sarah@ecprs.org) or Brenda Baker (bbaker@madisonchildrensmuseum.org), children’s museum sector organizer and project advisor.

Stephanie Shapiro and Sarah Sutton co-founded the nonprofit organization Environment & Culture Partners (previously Sustainable Museums) in 2021 to strengthen and broaden the environmental leadership of the cultural sector. Sutton, CEO, now lives in Tacoma, Washington; Shapiro, managing director, lives in Washington, DC.

| This article is part of the “Children’s Museums and Climate Change” issue of Hand to Hand. Click here to read other articles in the issue. |

By Langley Lease and Paige Childs, National Children’s Museum

Engaging children and their families in a meaningful dialogue around climate change can be tricky, to say the least. How do we playfully introduce children to this serious topic and inspire them to take action?

Answering this question became a priority in 2018 during the early stages of developing the newest iteration of National Children’s Museum, which opened in February 2020 in Washington, DC. It was evident that climate change lacked representation when assessing the landscape of children’s museum content at that time. As an institution that combines children’s museum experiences with science center content, it felt both natural and necessary to dedicate exhibit space to such a timely and critical science topic.

With the help of educators and experts, the museum developed its Climate Action Heroes framework, which empowers young activists to defeat climate “villains” while exploring the science behind climate change. Located in our Innovation Sandbox space, this exhibit will live in our museum for at least the next two years. (More can be learned about the museum’s in-person and virtual Climate Action Heroes experiences in the November 2020 issue of Hand to Hand.)

Since the museum’s reopening to the public in September 2021, the in-person Climate Action Heroes experience has been named a favorite exhibit by 28 percent of visitors who complete a post-visit survey. The climate science-dedicated space in the museum has influenced our on-site and digital programming priorities, community partnerships, and future exhibit development. In fact, a Climate Action Heroes experience will soon make its debut at Dulles International Airport, where children will be invited to discover climate-friendly travel tips and challenges. Content is continuously added to the digital experience at www.climate-heroes.org, including monthly missions that share small ways young activists can help protect the planet.

At National Children’s Museum, our mission is to inspire children to care about and change the world. Our changing climate is one of the most important issues facing our world today. As stewards of the next generation, we believe it is our duty to empower and inspire young innovators and activists. This means committing to and expanding upon our work in climate science. Climate change and the important role today’s children will have in tomorrow’s solutions will remain an undercurrent in every facet of National Children’s Museum’s work, from our daily operations to the programs we offer. Climate Action Heroes is just the start.

Langley Lease is exhibits + experience manager and Paige Childs is communications + digital specialist at the National Children’s Museum in Washington, DC.

| This article is part of the “Children’s Museums and Climate Change” issue of Hand to Hand. Click here to read other articles in the issue. |

By Rachel Daigre, Cate Heroman, and Alexandra Pearson, Knock Knock Children’s Museum

In 2019, MakerEd, a nonprofit organization that brings maker education to communities, selected Knock Knock Children’s Museum to be a regional hub for Making Spaces, a two-year professional learning and capacity-building program designed to support local leadership around maker education, with an emphasis on sustainability and growth. Knock Knock then selected program participants, including fifty preK-third grade educators and administrators from eight elementary schools as well as staff from the nearby public library.

After Hurricane Ida passed through our region in August 2021, Knock Knock provided resources and guidance to help children cope after this natural disaster. To extend our reach, we decided to use our October Making Spaces training as an opportunity to help educators create supportive learning environments in response to severe weather events. We brainstormed how we might use making and tinkering experiences to accomplish two goals: 1) support the emotional needs of children during traumatic events and 2) help deepen their knowledge and understanding of weather-related events in our community.

To reach the first goal, we wanted to inspire teachers to create environments and provide experiences to help children:

To achieve the second goal, we talked about all the things that children might experience during hurricanes: strong winds, power outages, downed trees, flooding, community helpers, lost or destroyed toys, lost pets, gas shortages, long lines, no electronic games to play, giving/receiving donations, damaged buildings, evacuating, relocating, and more.

With these two goals in mind, we set up activities throughout the museum that educators could explore and later implement in their classrooms. The public library assisted by sharing children’s books—both fiction and nonfiction—to support children’s understanding of this weather disaster and to help them cope with their feelings. Teachers quickly realized how they could use the making and tinkering experiences listed below to help children recover from the effects of severe weather events:

Big Backyard: creating weavings and faces with items from nature;

Maker Shop: creating homemade circuit switches in a homemade neighborhood that could be broken by tree limbs, making battery-operated fans and flashlights, making whirligigs powered by wind;

Art Garden: creating miniature Zen gardens, making string art by hammering nails and wrapping them with string, wrapping sticks with yarn to make patterns;

By-You Building: exploring wind at the wind tunnel, building strong houses and water bottle forts;

Paws & Claws: designing and building pet carriers, creating lost pet posters;

Geaux Figure! Playhouse: creating homemade board games;

Go Go Garage: using a homemade grappler tool and working as a team to move roadblocks and ease traffic on the racetrack, playing with model bucket trucks;

Bubble Playground: making floating boats, discovering items that sink or float;

Story Tree: exploring books related to hurricanes as well as supporting the emotional needs of children.

After an hour of exploration, the educators met by grade levels to reflect on these questions:

With the increasing occurrence of hurricanes and floods, children in our community are experiencing phenomena that are difficult to comprehend. Planning new ways to help them and their families understand and rebound after disasters is critical. Making Spaces teachers walked away with making and tinkering strategies to use now and in the future to help children cope, deepen their knowledge, and spark their curiosities.

Rachel Daigre is director of learning innovation; Cate Heroman is education committee chair; and Alexandra Pearson is Maker Shop manager at Knock Knock Children’s Museum in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 4.14, the final report in the fourth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

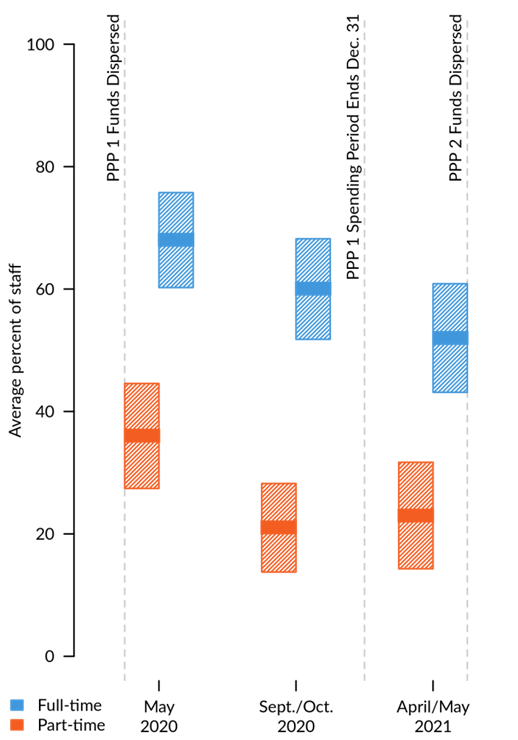

This is the final report in the Museums in a Pandemic volume of the ACM Trends Report series. Since March 2020, the ACM Trends Report team has tracked the impacts of the pandemic on children’s museums through surveys, conversations, and other data collected by ACM. This ACM Trends Report presents data from museums that responded to our Spring 2021 survey.

Throughout the pandemic, we collected data on children’s museum operations and what was vital to their survival. We benchmarked this information against 2018 fiscal year 990 data. We used these data because 2018 represents the last pre-pandemic fiscal year for all of the organizations in our sample set. This comparison helped us understand the pandemic’s impact on museum operations.

As the pandemic continued into 2021, children’s museums were balancing re- opening to the public with the continued need to focus on securing necessary funding to keep operations going. We documented ACM members’ fundraising efforts in the early stages of the pandemic (ACM Trends #4.2 and #4.7).

By Spring 2021 many museums were welcoming visitors back into their spaces, with new safety protocols in place and varying capacity restrictions. Museums rely on these patrons to sustain operations. When we reviewed 2018 990 financial data from 218 museums in the ACM member network, our analysis showed that the median institution (regardless of size) relies on program services income (this includes income derived from admissions, events, and other general operational activities) for roughly 45% of its total income. Attendance directly impacts how museums balance income and expenses. By the time of this survey in Spring 2021, the numbers of visitors to the museums had not returned to pre-pandemic levels. This dip continues to impact children’s museums’ income.

To track how the field’s attendance had changed throughout the pandemic, we captured monthly total attendance numbers from March 2019 to March 2021. Sixty-two museums responded to this portion of our Spring 2021 survey. From this data set, we know that the average museum was open to in-person visitors for 34% of the total days during the pandemic’s first year than the year prior. Additionally, based on survey data from 52 museums, we know that in March 2021 attendance for the average museum remained at 26% of pre-pandemic attendance levels.

Knowing that museums rely on their patrons for 45% of their total income from program and services revenue, we asked for up-to-date data, as of March 2021, on fundraising during the pandemic. Specifically, we looked at governmental and non-governmental funding sources. As we reported in ACM Trends Report 4.7, the median value of funding from governmental sources in September 2020 was $205,000 (N = 96). Of the 96 museums responding, 77 had approached private funders (ACM Trends #4.13) with an average return of $50,000.

A second round of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) funding was awarded in early 2021, in time for award announcements before the Spring survey. At this time, most museums responding to the survey (n = 80) reported moderate success in obtaining government funds during and related to the COVID-19 pandemic, exhibiting an 80% success rate with a median value of almost $400,000. Appeals for private funding were even more successful (98% success rate) but yielded smaller amounts, with a median value of just over $100,000.

Two new streams of funding were available to museums to apply for through the American Rescue Plan Act and the CARES Act. In March 2021, nearly one-third of museums (n = 27) indicated that they had applied or intended to apply for a Small Business Administration Shuttered Venue Operators Grants (SVO). At the time of the survey, SVO had not yet been distributed.

Additionally, just over one-third of museums (n = 32) indicated that they had received Employee Retention Tax Credit (ERTC) funds, with the median museum receiving $290,328. We have not collected further data on either the ERTC or SVO at this point.

Fundraising success is about more than securing grants. Museums are constantly looking for new funding sources and streams and setting goals to meet operating budgets. This remained true during the pandemic. Reviewing 218 museum’s 990 information, we found that the median museum relied on donations for almost half of their total income. In the Spring 2021 survey, we asked children’s museums whether their fundraising efforts were more successful, just as successful, or less successful during the first pandemic year (March 2020 – March 2021) compared to the previous year. Three-fourths of museums indicated that fundraising was just as or more successful during the first pandemic year (n = 79).

In Spring 2021, children’s museums were generally confident that they could meet their financial obligations one year on in Spring 2022. Eighty museums responded to the question “How confident do you feel that your museum will be able to maintain its financial obligations to maintain operations a year from now?” on a scale from Not at all confident to Very confident. Slider responses were recorded as numerals between 0.00 and 1.00, accordingly.

Seventy-three museums responded with a degree of confidence equal to or higher than 0.5, indicating that museums had found a way to compensate for the financial hit caused by drastically lower attendance numbers.

Government funding proved vital for many museums. Overall, their fundraising success during the pandemic seems to have stimulated children’s museums’ confidence.

Figure 1 above is a Box and Whisker Plot displaying the responding museums’ confidence (n = 80). We will explain each element of the Box and Whisker Plot and what it shows about our data. Box and Whisker Plots are useful for displaying the range of values in a dataset, including the median value and quartiles of the data’s spread. Each quartile includes 25% of responding museums. Here, the orange box shows us the second quartile, the third quartile, and the median values of our data. The median is represented by the vertical line down the middle of the box. The left “side” of the box displays the second quartile, and the right “side” of the box displays the third quartile. The purple dot in the second quartile is the mean, or average value, of our data set. The whiskers, or the horizontal lines, on either side of the box show us the first and fourth quartiles. The five blue dots ranging between 0.10 and 0.45 are outliers.

So, what does all this mean in the context of museums’ confidence in meeting their financial obligations? By looking at the median, we can tell that the middle value of our data set represents a museum that is quite confident that it will meet its financial obligations in Spring 2022.

On a scale where a rating of Not at all confident yields a value of 0.00 and a rating of Very confident yields a value of 1.00, a median value of 0.85 reflects fairly high confidence. Meanwhile, the orange box tells us that half of the museums in the dataset, or 40 out of 80 museums, are moderately to very confident that they will meet their financial obligations in Spring 2022.

The short right whisker tells us that 20 museums are very confident in their ability to meet their financial obligations. Of the remaining 20 museums, five (represented by the blue dots) are less than confident about meeting their financial obligations. The box’s long left whisker shows that the first quartile of museums is somewhat confident in meeting their financial obligations. The takeaway is this: 75% of the museums in this data set are moderately to very confident that they can meet their financial obligations in Spring 2022. In the following sections, we explore the reasons for their optimism.

Every museum has a unique rationale for any confidence it has about its late- and post-pandemic future. However, we identified six general categories that illustrate why museums are right to feel confident. Thirty museums referenced a diversified funding stream, including federal and local government funding as well as private funding, as a reason for confidence. Twenty-seven museums have been encouraged by attendance during their re-opening phases and have received more visitors than anticipated. Twenty-three museums indicated that a reduction in operational spending as part of a long-term planning strategy, along with current cash reserves, meant they could be confident about meeting future operational needs.

Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, reducing operation spending also included a reduction in staff. We detail the impacts of staffing over the course of the Pandemic in ACM Trends Report #4.12.

Additionally, seven museums in our data set either belong to a larger museum/university structure or are completely funded by local government and have moved to more sustainable budgets to ensure future operations. Finally, one museum mentioned that rent reduction has been helpful, and four museums moved into new spaces with higher capacity and lower operating costs.

In the past year, museums have reimagined their operations and service to their communities, and this has affected their staff. During an ACM Leadership call in Fall 2021, about 6-months after the Spring 2021 survey, ACM and Knology followed up with roughly 20 ACM member museum leaders to hear if they were still confident in meeting their operations’ budgets in 2022.

With attendance not yet back up to pre- pandemic levels, museum leaders’ confidence in meeting financial obligations in 2022 was high yet speculative. On a scale of 1 (least confident) to 5 (most confident), museum staff on the call indicated confidence between 3 and 5, with specific caveats and new concerns. Key concerns centered around the continued need for federal and state governmental funding to fill in the gaps of lowered earned revenue. Specifically, the Shuttered Venue Operating Grants and PPP loans were still covering many 2021 costs and were projected to continue to support museum operations into 2022. A second round of SVOG and funds from the Employee Retention Tax Credit were noted as potential future governmental funds that these museums were banking on. A museum CFO noted that, “Once the federal funding runs out, our confidence drops off tremendously not knowing which direction covid stats are going to go. Just when we thought it was getting back to ‘normal’ the Delta variant picked up. What’s next?” This was met with widespread agreement from others in attendance.

Museums staff noted that donations from individuals and foundations were starting to taper off, with many noting that perceived “sympathy giving” at the height of the pandemic in 2020 was not as common in Fall 2021. Many did not expect their fundraising to be as successful in 2022 compared to their early pandemic success.

We will continue to monitor the state of the children’s museum field into 2022 to understand how these concerns impact their missions and operations.

The data used in this report came from an online survey that ACM sent to US-based children’s museums. Overall, 91 museums responded to at least part of the survey. All participating museums were based in the US. Additional data was collected through an ACM Leadership call discussion forum where data was presented back to museum leaders for their response.

Flinner, K., Voiklis, J., Field, S., Attaway, E., Gupta, R., & Fraser, J. (2020). Museums in a Pandemic: Financial Impacts. ACM Trends 4(2).

Flinner, K., Voiklis, J., Field, S., Thomas, U.G, Attaway, E., & Gupta, R. (2021). Museums in a Pandemic: Diversifying Funding Streams. ACM Trends 4(7).

Flinner, K., Field, S., Voiklis, J., Thomas, U.G., & ACM Staff (2021). Museums in a Pandemic: Personnel & Rebuilding Teams. ACM Trends 4(12).

Fraser, J., Field, S., Voiklis, J., Attaway, E., & Thomas, U. G. (2021). Museums in a Pandemic: Patterns in Fundraising. ACM Trends 4(13).

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

| This post was originally published as ACM Trends Report 4.13, the thirteenth report in the fourth volume of ACM Trends Reports, produced in partnership between ACM and Knology. |

Since May 2020, the ACM Trends Report team has tracked the impacts of the pandemic on children’s museums and the field’s innovations through survey studies and other data collected by ACM.

This ACM Trends Report presents data from 28 museums that shared information on their donors and funds received by Spring 2021. This includes 147 corporate donations and 119 private foundation donations made to children’s museums. Corporate donations were stratified into categories by type of donor. We also collected data on whether the funds were provided as restricted or unrestricted gifts. To understand the pandemic’s impact on donations, this information was benchmarked against 2018 fiscal year 990 data. Comprising the most complete data to date, the 2018 fiscal year represents the pre-pandemic fiscal year for all organizations.

Three small museums, 10 medium museums, and 11 large museums provided information on corporate donations received during the pandemic. We also learned about a few extraordinary donations that represented historical commitments to large children’s museums, which should not be considered typical of the day-to-day fundraising expectations.

This early assessment of donor type, scale of donation, and comparisons helped us learn how to support comparison between museums irrespective of scale.

We normalized the data by comparing the percentage of total income from corporate and private funding received during the 2018 fiscal year to the percentage of total income from corporate and private funding received during the pandemic. This way, we were able to develop clear benchmarking that can be used by all children’s museums to consider their relative prospecting success and opportunities in their markets. This report focuses on understanding how to benchmark and set reasonable expectations for donation size as our field emerges from the pandemic.

An assessment of the 2018 nonprofit tax filings for all ACM member museums showed that an average children’s museum receives 47% of total income from donations and gifts. While some museums rely more heavily on donations than others, museum size did not impact total percentage of income from donations.

Museum development teams build an understanding of their local supporters and focus on relationships that can last over time. As a result, many of these gifts may be a function of annual giving unique to each community. This report focuses on whether there are patterns to giving that can help museum leadership set expectations. The context for this study was the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 civil rights protests, which caused donors to reconsider their funding priorities.

We explored a snapshot of fundraising results from the 2020 pandemic year to assess how these varied from pre- pandemic times. We also looked at donors by industry to aid in benchmarking anticipated gifts from any representative of the sector, and whether being part of a local, regional, or national brand impacted the size of gifts.

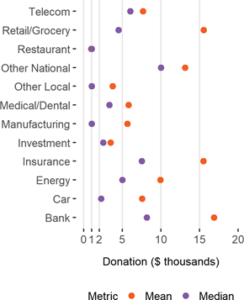

Twenty-four museum respondents reported corporate donations received during the pandemic. These donations ranged from $100 to $100,000. Most donations were below $5,000 (Figure 1). Around 2/3 of donations (n = 98) were gifted as unrestricted funds, 40 were completely restricted, and six were partially restricted. Larger donations were more likely to have restrictions attached.

Let’s walk through how to read this figure. Each black circle represents an individual donation from a corporation or corporate foundation. The purple line shows the mid-point (median) of the distribution of donations. The orange line represents the average (mean) corporate donation in this dataset. The mean is calculated by summing up all the numbers in a dataset and then dividing by the number of values in the dataset. This is different from the median which refers to the middle number when a set of numbers is placed in order smallest to largest. Three outlier donations (two of $70,000 and one of $100,000) are not shown in Figure 1 but are included in calculations.

Because firm size and industry impact corporate giving (Amato & Amato, 2007), we categorized the set of corporate donations by industry and discovered that different-sized corporate donors gave varying gift amounts. To understand how to benchmark these gifts for comparison purposes, we suggest that is more relevant to consider the “median” donation rather than the “mean,” as one large donation to one museum can skew the results of the average.

Let’s walk through how to read the next pair of figures. Here, the circles represent donations from corporate donors and corporate foundations to children’s museums. The purple circles show the median donation for each industry while the orange circles show the mean donation for each industry.

Figure 2. Comparing the mean and median donation to children’s museums from corporate donors and corporate foundations.

Our analysis of this small dataset suggests a few things, but we would need additional data to more fully understand the funding patterns of corporate donors and make recommendations as to how children’s museums might approach them. These data suggest that if a museum were to approach an energy company for funding, they might be more likely to succeed if they explain that many children’s museums are supported by energy companies at the $5,000 level, but a few energy companies make large gifts that average $10,000.

While this approach may seem to reduce the potential gift, it helps to establish two norms or social expectations for the industry that could benefit children’s museums in the long term. Industrial and organizational research has shown that corporate donations are likely to level to match the norms for their industry, but are modified by regional norms across industries (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2016). Presenting funding request in this way may increase willingness of corporate donors to consider small gifts that were not on their priority list because they wish to represent their corporate citizenship as consistent with industry standards.

We also categorized corporate donations by the service territory. National brands were more likely to donate in the $10,000 range, regional brand gifts were at the $5,000 level, while local businesses hover around $1,000 (Figure 3). As noted, these are early findings, and we will continue to gather additional data in future surveys.

The complete corporate funding data represents information from 24 children’s museums, a number too small to generalize across the field. A qualitative comparison of these data does suggest that in 2020, larger museums faced more challenges securing donations that matched historic patterns. In our data, medium sized museums fared better than their larger counterparts, but only a few maintained the pre-pandemic pace. Figure 4 presents a picture of 2020 corporate and private donations and the shortfall from 2018. To create the graph. we normalized the 2018 data for every museum to 100%, then divided 2020 funding into three categories and added a fourth representing 2020 donation shortfall compared to 2018. Private philanthropy in 2020 was by- far the most important category for supporting museums at about 3x the value of corporate donations (Figure 4), but still well below pre-pandemic levels of support.

Fundraising in the pandemic was vitally important for most children’s museums to fill the loss of earned income. As explored in earlier reports in this series, many museums reimagined their operations and services to accommodate fiscal realities, including a recognition that donors were reprioritizing funding. This ACM Trends Report shares data demonstrating useful patterns in fundraising, which can inform how museums can leverage industry norms to launch new requests to local, regional, and national corporations. However, more data needs to be collected to pain the full picture of corporate and private giving. In this report, we also normalized data by museum size to allow for comparisons irrespective of scale, while still allowing us to understand how scale will continue to influence public support for children’s museum funding.

The data used in this report came from an online survey that ACM sent to US-based children’s museums, and the 990 public tax filings of all U.S. children’s museums who are members of ACM.

Amato, L. H., & Amato, C. H. (2007). The effects of firm size and industry on corporate giving. Journal of Business Ethics, 72(3), 229-241.

Flinner, K., Voiklis, J., Field, S., Thomas, U.G, Attaway, E., & Gupta, R. (2021). Museums in a Pandemic: Diversifying Funding Streams. ACM Trends 4(7). Knology & Association of Children’s Museums.

Marquis, C., & Tilcsik, A. (2016). Institutional equivalence: How industry and community peers influence corporate philanthropy. Organization Science, 27(5), 1325-1341.

This project was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

The Associations of Children’s Museums (ACM) champions children’s museums worldwide. Follow ACM on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Knology produces practical social science for a better world. Follow Knology on Twitter.

January 12, 2022 (ARLINGTON, VA)—The Board of Directors of the Association of Children’s Museums (ACM) today announced Arthur Affleck as Executive Director, starting January 31, 2022. Following an extensive executive search, the Board unanimously selected Affleck to lead ACM, the world’s foremost professional society supporting and advocating on behalf of children’s museums, with more than 470 members in 50 states and 16 countries.

“We are thrilled to announce Arthur Affleck as ACM’s new leader,” said Tanya Durand, President, ACM Board of Directors, and Executive Director at Children’s Museum of Tacoma, powered by Greentrike. “ACM’s growth and development under the leadership of Laura Huerta Migus offers Arthur and the Board a wonderful foundation upon which we will build the next phase of ACM’s service to the children’s museum field and to families worldwide. Arthur brings to us impressive resource development experience, museum field savvy, and has a solid reputation as a connector and a doer. We look forward to working with him to set the most exciting vision for ACM yet.”

With considerable experience in nonprofit work and higher education, Affleck most recently served as Executive Vice President at the American Alliance of Museums (AAM), where he led an array of AAM programs and services, including membership, development, and meetings and events.

“Arthur’s vision, leadership, and many contributions to the museum field as part of AAM’s leadership team for the past five years has prepared him well for this new role,” said Laura Lott, President, AAM. “ACM and its members will grow and thrive thanks to Arthur’s dedication and talent. I could not be more pleased by his appointment.”

During his tenure at AAM, Affleck helped to secure seven-figure foundation grants to support the Alliance’s ground-breaking Facing Change—Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Inclusion Initiative. He worked to advance DEAI efforts and financial sustainability for both the Alliance and museum field, as well as to expand museums’ growing role in the Pre-K-12 education ecosystem.

“I am excited by the opportunity to serve as Executive Director of the Association of Children’s Museums and to lead the effort to champion children’s museums worldwide,” said Affleck. “At this moment in our history, we need museums more than ever—especially children’s museums. In partnership with the board and staff, we will continue to support our members and advance the field in ways that are responsive, innovative, and impactful.”

| This article is part of the “Inside the Curve: Business as (Not Quite) Usual” issue of Hand to Hand. Click here to read other articles in the issue. |

By Pam Hillestad, Glazer Children’s Museum

I believe passionately in silver linings, but I have to admit that even my optimistic ideals were shaken to the core when we re-opened the Glazer Children’s Museum in June 2020. None of us knew what to expect. From a business standpoint, I wasn’t sure how we were going to recover, but I was even more worried about how we were going to create a positive experience for families coming out of quarantine. Would they come? What would they expect? What would they need? We weren’t sure, but we hoped that if we watched and listened we would figure it out.

Fairly quickly, we noticed that groups stayed together and experienced the museum differently than they had in the past. They remained in family units and were much more aware of where their children were and what they were doing throughout their visit. No longer distracted by phones, conversations, or the outside world, adults appeared more physically and mentally involved in their family’s visit. The reality of the threat of COVID-19 and navigating a new normal seemed to force them to be more present in the moment. We saw caregivers genuinely immersed in their children’s experiences.

We were not surprised that caregivers were newly cautious, but we were excited at the renewed attention they gave to their children and the overall level of family engagement. Preparing to add daily programming back into the schedule, we asked ourselves, “What if we could create programming in such a way that even when COVID-19 is no longer a concern, families still exhibit this kind of engagement during museum visits?” In an attempt to answer this question, we re-imagined our daily programming schedule and began to prototype what eventually became the Family Play Project (FPP).

First, we set up a programming area designed to give families their own spaces within it. The museum has two staircases. When we reopened, we designated one as the “up” staircase and one as the “down” staircase. The programming space we chose at the top of the “up” staircase was immediately visible and welcoming to families as they made their way to the second floor. In this 1,100-square-foot area, we set up six small, family-sized tables, six feet apart, and put a bottle of hand sanitizer on each table. Our program team staff, called playologists, stood near the top of the stairs and invited guests into the area to try the day’s activity. They shared materials and instructions with families by placing items on colorful trays and passing each family a tray as they entered the space and sat at their own table to participate.

In the first few months, activity themes changed frequently. On one day, we would offer an art activity at 10:00 a.m. and then a STEM activity at 11:00 a.m., for example. In one of these first art programs, playologists gave families a tray of leaves and other natural objects and invited them to use a glue gun, eye stickers, paint sticks, and other materials to create an animal or picture of some sort to either leave on a gallery wall or take home. After handing each family a tray, playologists then stepped aside to allow them to complete the activity on their own. Initially intended to keep both staff and guests at a social distance from each other, this type of “hands-off” programming was a big shift for everyone. Our playologists were used to interacting with children face-to-face while parents either opted out or participated in a cursory way. Families were used to letting us guide their play.

We put this new format in place as a temporary measure to help staff and guests feel safer. However, we soon found it also gave our program team time to observe and encourage family play. More importantly, we discovered it allowed caregivers more time and space to engage deeply with their children around the program. It wasn’t just that they were keeping closer tabs on their children’s physical location during a museum visit; we now saw a new level of interest in the programming activities. We saw deepened, joyful connections and knew we had stumbled upon something important.

As you can imagine, the initial change was not easy for the playologists. The moments of joy the team had formerly experienced working one-on-one with children had been transferred to the caregivers—and that was a hard adjustment at first. The team missed their old interactions with children and weren’t sure they were doing their jobs correctly anymore. After all, who were we, if we were not directly instructing or playing with children? That question led us to take a deep dive into the world of playwork and to begin to determine for ourselves where the intersection of museum play, family play, and playwork lay.

We had to dig in, examine our mission, consult our strategic plan, and determine who we wanted to be and who our families needed us to be—now. And while a little painful at the time (isn’t all change painful?), it was ultimately revelatory. This process has put the museum on a path, toward not only establishing ourselves as convening experts in the field of play, but also centering ourselves in the community as champions of play for children and families. Within a few weeks not only had the percentage of engagement in our daily programs grown, but so too had the amount of dwell time in them, the quality of the interactions, and both the level of participation and overall satisfaction of caregivers. The daily program participation capture rate soared under 10 percent in 2019 to 34 percent in 2021. We felt we had found the holy grail!

By stepping back and providing families with tools, we were building a more meaningful programming space. To celebrate this discovery, we decided to put all of our daily programming “eggs” into the family play “basket,” and we have not looked back. Prior to the pandemic, we had the typical scheduled programming at timed intervals and in different locations throughout the museum. Now we are committed to open programming throughout the day and primarily in one location.

The Family Play Project’s discovery phase continued through the fall of 2020 in the dedicated “up” staircase area. Frequently observing families in the space, we tracked daily metrics as well as dwell times. Families were engaged and having fun, and we were learning how to interact with them from the sidelines, wearing what Penny Wilson calls “the cloak of invisibility” in her essay, “The Playwork Primer,” published by the Alliance for Childhood.

By late December, we were posting daily capture rates over 30 percent. We instinctively knew that this was not simply a COVID-19 phenomenon, but that we had stumbled on the great white whale in children’s museums: a way to build relationships with caregivers and give them the support and space they needed so that they could enjoy a meaningful and playful experience with their children.

By January 2021, based in part on metrics and in part on gut feelings, we decided to continue the Family Play Project format for our daily programs in the upstairs space. But instead of running a couple different daily programs, with ever-changing themes, we selected one theme per month, allowing us to deepen the impact. Phase 1 of this new iteration involved building a Family Play Project calendar, choosing a theme for each month and tying as many of the other daily elements and museum spaces of the museum into it. Our first extended focus topic, bears, was an introduction to the Wild Kratts exhibit that followed. A screen in the FPP area was tuned to a Panda Bear webcam, and families learned how to fold origami bears together in the project activity. In addition, playologists learned a number of interesting bear facts to share with guests and all of our story time books were about bears.

Along the way, we also discovered the well-branded Family Play Project was very appealing to partners and donors. In April 2021, we partnered with Tampa Bay Water and created a Family Play Project with a special emphasis on water. Families stepping into the “up” staircase space were welcomed by water-related images on the walls, including art by First Nations Artist Christi Belcourt portraying the interconnectedness of nature and images explaining the water cycle. Families received a tray that included a black sheet of paper, oil pastels, and a copy of a family water pledge, which they could sign. Bilingual signage on each family table shared information about Christi Belcourt as well as some key water-related vocabulary words, such as aquifer, mangrove, and percolation. Children were captivated by the oil pastels, and adults were intrigued by the artist and her technique, which is characterized by rich, saturated colors that look like native beadwork, frequently on a dark background. Many families signed the water pledge as well.

The Family Play Project nicely illustrates the lessons we have learned about family play. While children are almost always eager to participate in an activity, choosing a topic that also interests caregivers increases family involvement. Currently, Family Play Projects are planned well in advance and integrated into the broader museum program. Some months the focus is attached to a partner (Tampa Bay Water) or an exhibit (Daniel Tiger), while other months it is attached to an event (celebrating the museum’s birthday). Each month we develop a theme-based, scaffolded family play activity, a story time book list, a musical play list, and a felt wall in the play space. The Family Play area is open all day long and families participate on their own schedule. Playologists are focused on inviting people into the area and supporting them, while giving families space to do the activities themselves.

We are still in the process of determining exactly what elements complete the perfect recipe for a meaningful, playful family experience, but we are learning more every day. In retrospect, Meditation and Mindfulness, our least successful theme, seemed to be an unfamiliar topic to caregivers, with activities like trying yoga poses and writing affirmations. What seems to consistently work best are themes that involve a lot of loose parts for children and a reason for caregivers to pay attention (either an intriguing topic or a perceived dangerous or “adult” tool, like a glue gun or hammer). Over the last eight months, we have continued to add and tweak elements, consult our play experts and families, and work cross-departmentally to develop a framework that captures what we are seeking. Our current model for the ideal project includes family learning goals based on topics we believe will delight and appeal to both children and adults, such as the use of interesting or novel tools (microscope, skin tone crayons, oil pastels), colorful tabletop and wall signage, multimedia elements, and an opportunity to either display a project on the gallery wall or take it home.

This summer, we added an intercept survey to our metrics, and now ask random families to complete a short survey on their way out of the programming space. To date, responses show that 91.7 percent of caregivers agree or strongly agree their child/children discovered something new about themselves and/or others today; 84 percent agree or strongly agree they discovered something new about themselves or their child today; and 97 percent agree or strongly agree they had fun. These responses have convinced us not only that are we headed in the right direction, but also that we are filling a need for the families we serve. Currently under development, a research project with the Department of Child and Family Studies at the University of South Florida will further probe FPP outcomes and results will guide future work in this area.

While so many difficult and awful things have happened during the past year and a half, we are thankful and extremely glad we took the time to watch, learn, and listen to our families when they returned to the museum. Their vigilance in protecting their own families struck a chord with us and the Family Play Project grew from there. We have recently added back some daily pop-up activities in other areas of the museum throughout the day. Families are starting to relax and sometimes will even join another family at the FPP table. On the whole, they are still more engaged than they were pre-pandemic. It is our deepest hope that the lessons learned will inform our future playwork and help families continue to build deep connections through play.

Pam Hillestad, vice president of play and learning, has served at the Glazer Children’s Museum in Tampa, Florida, since 2017. Previously she was a high school English teacher and soccer coach on U.S. Military bases in Portugal, Turkey, Bahrain, and Italy.

| This article is part of the “Inside the Curve: Business as (Not Quite) Usual” issue of Hand to Hand. Click here to read other articles in the issue. |

Before assuming her current role as Lead Arts Educator and Developer in June 2021, Liz worked for twelve years in a variety of other positions at the Chicago Children’s Museum (CCM). Most were part-time, enabling her to also work for Chicago Public Schools as a middle school and high school art teacher.

Liz came to Chicago from Houston, Texas, to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2005-2009). As a teen, she volunteered at Children’s Museum Houston and worked on the Teen Council at the Contemporary Arts Museum of Houston. She describes herself as “a bit of a museum nut!” Along the way she got a master of teaching degree in art education at Columbia College (2013), worked at a zoo, and sold bath bombs.

Let’s Grow Together, a visitor-created art exhibit, was born out of a desire to celebrate reopening the museum in June 2021. In a large display case located in a well-trafficked hallway (across from the dinosaur), Liz developed a program to transform the space to welcome returning children and families. Liz: “So much loss happened while we were closed. But I didn’t want to focus on that so it was natural to think about growth instead, and gardens immediately came to mind. We can’t see all the emotional and social rebuilding that’s happening within us, but we can see a garden grow.”

For Liz the exhibit was a “great mental challenge as a developer/educator.” Guests dropping in to the Art Studio could make a leaf (or a flower or a bug) and either take it home or tack it to a burlap wall in the studio. Because individual leaves, flowers, and bugs were made over eleven weeks by young visitors, she couldn’t anticipate how the mural would look from week to week. When the museum was open from Friday through Sunday, Liz worked in the closed museum during the week to gather parts that had been “planted” on the burlap wall (seen in panel #1 of the cartoon) to assemble into the hallway mural. (Panel #2 shows the visitor process in action.)

Liz uses cartooning as a tool to help develop other exhibits and programs. In the cartoon presented at left, Liz portrays the many components of Let’s Grow Together—from the participating artists (kids), to their families/caregivers, to the staff, to the ideas and feelings that the project sparked—in six meaningful and delightful panels.

Let’s Grow Together’s garden beds are full now but will remain on display for the coming year. —ED

In panel #3, week 1-5 shows flowers, week 5-8 leaves, and week 8-11, bugs. Were you encouraging a botanical story progression? As a gardener, I noticed flowers come before leaves. Huh? But I also notice you included the bugs! Oh, the bugs…

Liz: Good eye on noticing we planted out of order. Flowers don’t come first, but we started there because it was so bare! I love leaves, but maybe our returning guests wouldn’t find them as interesting as flowers. As it turned out, leaves were the most popular! Just yesterday, a three-year-old talked to me about how he continues to make leaves at home. We ended up with “body builder” leaves, “cat” leaves, “dragon” leaves, “alien” leaves, and “COVID mask” leaves. From a practical standpoint we did leaves second so I could more easily arrange them naturally in bunches around the flowers. (You can see the whole process on my Instagram highlights— instagram.com/lizziemaerose.)

Through Let’s Grow Together, what have you discovered about the kids in your audience?

Liz: I was amazed at how they really embraced the unique aspect of it all and how responsive they were! We are really into process-based education in the Art Studio at CCM and so I would show them folding techniques to work with symmetry. And that was it! They came up with whatever they wanted! I didn’t think two- or three-year olds would get the symmetry bit very well, but they really seemed to enjoy it.

Your Instagram feed has a lot of cartoons that seem museum-related, e.g. Lay off the Masters, Sock Puppets, Scribbling, Bird Creative Play, etc. Do you actively push these out to museum audiences? Are they related to other programs at the museum?

Liz: Some of my comics have been featured on our CCM Instagram page. During pandemic quarantine, an artist I know asked me to make comics for her to share with her many followers who were caregivers. So, for a while there I challenged myself to make a comic every weekday. She would share them with her followers, and I shared them with mine. I was working very little at the museum at the time. All my videos were made in my own apartment! (I’m the gal with purple hair.) So, yeah, I wanted to help people in the best way I could—with play tips!

Under the developer umbrella, I am also currently working as an illustrator at the museum. I make illustrations to highlight upcoming projects or to help people understand how our spaces can spark play. My illustrations are very comic-like too. Even though these past eighteen months have been really tough, it’s been a great opportunity to try new things.

Do you regularly use cartooning to help develop programs?

Liz: I definitely use how I think about cartooning in my work. A challenge with cartoons is the balance of visual and word. I see that same challenge when introducing activities in the museum. I want kids and grownups to use their imaginations and the visual cues all around to inspire their making. So, sometimes I have to hold back. I can get too wordy in my comics too—ha-ha!—and, dare I say, in this interview!? Every museum experience is unique. For some guests it is their first visit; others are regulars or having a special family time together who may not want an educator talking to them very much. So I designed the Art Studio space to do a lot of the communicating on different levels.

What are the advantages of using cartoons in program development, over the usual written word or conversations? What can you communicate in a cartoon that’s hard to capture otherwise?

Liz: Accessibility! You’ll notice I tried to include Spanish translations in my cartoon (examples in panels #1 and #2). During the pandemic I worked with a colleague who is a native Spanish speaker (Hola, Alex!). I thought really critically about how to use Spanish meaningfully by making the text equal in size along with the visuals! If you don’t speak English or Spanish, a picture can help you understand something. When you travel to a place where another language is spoken, you can tell the power of simple images when you are looking for a bathroom. Or, where not to step. Also, for early learners, seeing a picture or simple cartoon of something and then the word is a classic phonics exercise. The simpler the drawing, the easier it is for our brains to “read” it or store the information.

The characters who appear in this cartoon—are they museum “regulars”?

Liz: Many of them are combinations of many regular visitors. The person in the hijab (panel #4) recently saw the comics and asked if it was her. Yes! An educator and artist who inspires me, she always wears bright and beautiful headscarves.

I also hide things, like cochlear implants, in my comics (seen in panel #5 in the little girl’s earlobe). The high school where I worked had a great “Hard of Hearing” program. I used to collaborate with the older high school students to teach our younger middle schoolers about sign language when I was introducing hand drawing.

I really love people, and many of them make it into my comics in different ways. All people should be able to find themselves in art.

How did you come into cartooning? Do you draw cartoons in other, non-museum aspects of your life?

Liz: I’ve been making cartoons since I was a child. In my teens I tried to move away from them because it wasn’t “cool,” but I kept going back to it. I have dyslexia and ADHD. My mind moves really fast. Comics are satisfying because I get to think about a million different things at once. Ultimately, I loved art because it was a place I excelled when I was struggling at school (I didn’t read until I was in 4th grade!). My parents were great and really encouraged it.

I try to draw every day, and not just art for work. Years ago, I saw people I knew on Instagram sharing art they were making and I decided I wanted to do it too. I have a comic about the power of envy. Occasionally jealous of what I saw among other people, I realized I had…unrealized desires. I also have a children’s book and a graphic novel I’ve been working on for multiple years. I don’t know if anything will ever happen with them because I work like crazy on one or the other for two months, then I don’t touch it for a year. I do take breaks when I need to but again, with the ADHD thing, I’m more stressed when I’m not doing something.

So yes, I do make comics in all parts of my life.

What do you think about when you draw a cartoon? How do you start? One idea/image, then a story flows from it?

Liz: I usually will begin with a thought I’m stuck on. A random memory pops up. Or something happens that totally changes my perspective. I write it in my notes app where I have dozens of ideas stored in no particular order. If an idea triggers a really big feeling, I will sketch out the comic, super messy, to get it out. Then later refine it.

Other times I’ll just go to the notes app and scroll until I find something that resonates with me at the moment. I tell my teen students to go with your gut, go with what you like. Art is about sharing with others things that give you a big feeling—good or bad. Preachy moment: art does not have to be made for a museum (except when it can?!). There is so much emphasis on the idea that art has to have some ultimate destination or objective—which also relates to the fact I’m a total play expert. If you want to get geeky about the definition of play (I got a comic about it), play is just doing a task for no particular reason.

| This article is part of the “Inside the Curve: Business as (Not Quite) Usual” issue of Hand to Hand. Click here to read other articles in the issue. |

By Kerrie Vilhauer, Children’s Museum of South Dakota

Following a fifteen-month closure, Dora Castano, custodian at the Children’s Museum of South Dakota, was looking forward to getting back to the little things—like cleaning fingerprints.

“I can’t wait to see little fingerprints on the windows again!”

Given the many tasks involved in a custodian’s work at a children’s museum, especially during a pandemic, it’s not often one would ask for more work to do. But, for Dora, those fingerprints aren’t just little messes.

They are a symbol of what was missing. They represent the unique role the people of the Children’s Museum of South Dakota play every day. They are the stories the museum learned to amplify, bringing our staff and volunteers to the world even when the world couldn’t come to us.

When it came time to reopen the Children’s Museum of South Dakota to visitors, it’s no surprise the bulk of the plan addressed health and safety. Messaging, talking points, and signage all focused on what guests would need to know when they came back to play.

As the team dug into the reopening communications plan, they quickly realized a more personal approach could go much further in reconnecting with visitors. After all, families had not been able to enter the museum’s doors—or connect with staff and volunteers in person—for over a year.

There’s precedent around this. The side effects of the pandemic—stress, developmental issues, and mental and physical health challenges—are real. Having a friend (or playmate) who is experiencing things in a similar way can be a comfort as society begins to move forward.

Which is why, when writing the reopening communications plan, we knew it was important to reintroduce the people behind the work—and the play—at the Children’s Museum of South Dakota. This strategy imparted empathy, showing how much a museum friend like Dora is ready to get back into the swing of things.

In a way, that set of fingerprints is a beautiful way to start a conversation.

Children’s museums are built for community. They are safe spaces for children, caregivers, and the surrounding area. As the only museum of its type in the state, this community space takes on an even more important role for the Children’s Museum of South Dakota.

Located inside a 40,000-square-foot repurposed elementary school on the edge of downtown Brookings, the museum takes on a more personal tone when guests arrive. Whether they are members who visit weekly, or tourists from many states away, the open-ended, child-led, inquiry-based way of play invites people into a relationship.

For many guests, it’s like coming home. It’s not uncommon for children to walk through the door and ask for a specific staff member or play guide. Some arrive and immediately look for a special loose part or toy—the life-sized stuffed sheep, or the large plush border collie, for example.

But as we all know now, reopening a children’s museum in a pandemic doesn’t mean things go back to the way they used to be. The museum knew we had to share safety protocols and guidelines that might make the play experience look different. We also knew that some protocols, like masking or limited capacity, could be controversial for some.

Here’s where those people and that community came into play again: by sharing the human side, guests could see that not only was health and safety a top priority, but so too was the fun.

This personal approach happened in two ways, first with a project headed up by museum educator Lauren Dietz and second, with the Museum’s Kidoodle Council Youth Advisory Board.

Tasked with freshening up a documentation wall in an exhibit just outside the art studio, Lauren wanted to show how excited the museum staff was to reopen. She connected with each staff member and asked what they were looking forward to the most.

She took photos of each person in their favorite exhibits. Because staff would be wearing masks upon reopening, she made sure one photo was with a face covering, and one was without, creating a balance of friendly smiling faces and safety protocols.

The project not only resulted in an inclusive, on-site display, but it also drove content for a digital campaign that spanned Facebook, Instagram, and the museum’s email list.

Amid messages about safety protocols, limited capacity, and adjusted hours, were the museum’s friendly faces—faces excited to reconnect, spark imagination, and learn through play. These faces belonged to long-lost friends who were ready to play again, even if it might look or feel a bit different at first.

And if engagement on social posts and guests sharing their excitement online and on-site is an indication of success, this was exactly what the museum’s audience was looking for.

The Kidoodle Council Youth Advisory Board is a volunteer group of nine six to twelve year olds who work as ambassadors for the museum and help generate ideas for programs and exhibits.

Throughout the museum’s closure, the board continued to meet through a combination of video conferencing and in-person meetings.

The Kidoodle Council had the honor of experiencing the first run-through of the exhibits prior to the indoor exhibit reopening. The council saw firsthand how to open and turn on exhibits, getting a behind-the-scenes sneak peek. In return, the museum staff could not only confirm everything worked as expected, but they also had a glimpse of how children would re-engage with the space following the closure.

The meeting resulted in a YouTube video that gave a time-lapse tour of the museum and shared what each board member was most looking forward to when they came back to play.

The video was shared with the public and used for staff training purposes. It offered new hires and those who haven’t visited in quite some time a chance to see the museum in action through the eyes of a child.

The pandemic put a hard stop to paid advertising. Even today, as the museum operates at limited capacity, advertising is on hold since play space continues to fill organically. However, the museum continues to look for ways to stay top of mind.

Whether it is offering ways to play along at home on the blog at www.prairieplay.org, continuing conversations on social media, or playing along in person, the museum will continue to focus on taking a personal approach. They know it’s these people—the ones who are excited to clean up fingerprints—who will help bring the museum back to life.

To stay in front of people. To follow the child. To be a resource. And to spark imagination that is as big as the sky.

Kerrie Vilhauer is director of marketing at the Children’s Museum of South Dakota in Brookings, South Dakota.

| This article is part of the “Inside the Curve: Business as (Not Quite) Usual” issue of Hand to Hand. Click here to read other articles in the issue. |

By Krishna Kabra, San Diego Children’s Discovery Museum

Inventiveness and ingenuity are stimulated by difficulty. When the going gets tough, we are forced to think in ways we never have, stretch beyond convention and comfort, and focus on positive outcomes or, at least, solutions.

People are creatures of habit. We stick to what we know and focus on what we’ve mastered (and can be bothered to do). We regulate for rote and plan for predictability, and it is in this overall balance that we find flow. We function with familiarity. The last year, however, has thrown a royal wrench in that highly evolved and deeply conditioned human tendency. The children’s museum field, like many others, has been flung into lands unknown, inadequately sourced, staffed, and skilled. Overnight, we have become artful adaptors, from mastering digital content production to going from staff commanders to staff counselors.